Energy Crunch Pushes Japan Into Era of Uncharted Coal Power

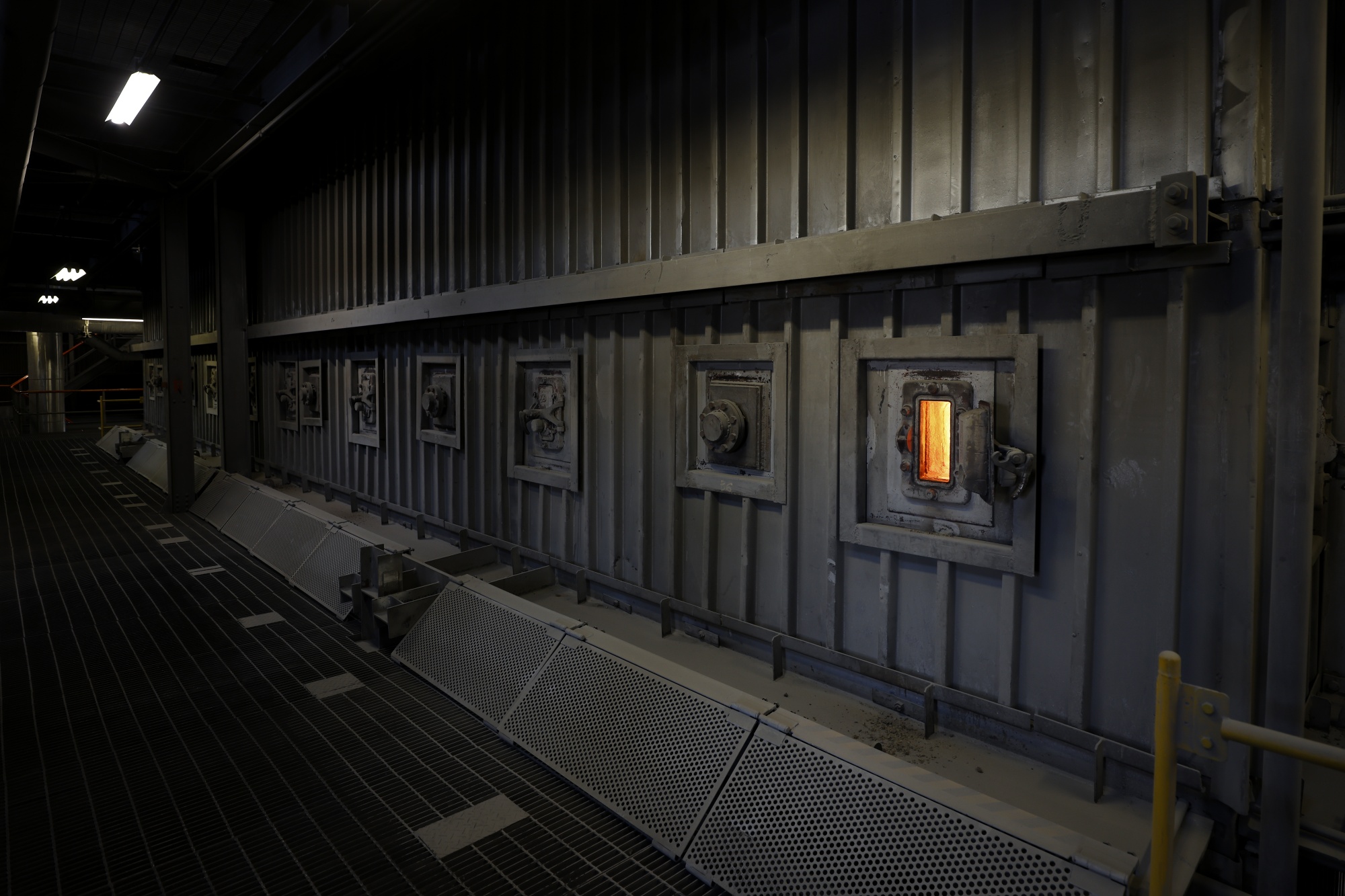

(Bloomberg) -- When Japan narrowly avoided blackouts this summer, part of the solution was output from aging coal-fired power stations like Takasago Thermal Power Plant.

Even as the nation aims to shift to cleaner energy sources, it remains heavily reliant on sites like Takasago, built in 1968 and considered far past retirement age. The plant, owned by Electric Power Development Co., or J-Power, has become even more vital amid a global energy crisis and shutdown of nuclear reactors since the Fukushima disaster.

“Usually, it’s good enough if a power plant operates for 20, 30 years,” said Hiroyuki Uchinaga, an official for J-Power’s maintenance unit and head of the Takasago plant, located in an industrial zone near the western port city Kobe. “We’re entering uncharted territory after operating for over 50 years.”

Electricity supply is expected to remain tight this winter and experts say extreme weather like this summer’s heatwave is becoming more common, meaning there may be demand for Takasago to keep running for much longer to keep the grid stable — even with the challenges that come with an aging facility.

Older power plants tend to be less efficient and more costly to maintain than newer models. Takasago depends mainly on workers to patrol the facility and detect irregularities, while newer plants have adopted more sensors and other monitoring technologies, Uchinaga said.

The continued shortage makes it particularly crucial for the Takasago plant, which provides electricity for the grid in Japan's western Kansai region, to run without major disruptions. The 500-megawatt, coal-fired power plant generates electricity equivalent to roughly a quarter of demand from households in the surrounding prefecture of Hyogo.

Uchinaga says the plant needs roughly double the number of staff compared with newer plants to patrol key parts of the facility. During the summer, temperatures around the boiler, which burns coal to generate steam that moves the turbine, rise to around 60 degrees Celsius (140 degrees Fahrenheit), creating a sauna-like environment for workers wearing protective gear and helmets.

Some of the monitoring processes seem almost instinctive, with workers touching the surface of equipment to check for temperature and vibration.

“You really have to use your five senses” to detect abnormalities in turbines, boilers and generators, Uchinaga said.

An ongoing concern is that some machinery parts were made by manufacturers who are longer in businesses. When they wear down, the plant’s workers need to make repairs themselves or work with other manufacturers to create them from scratch.

Running old power plants “adds onto maintenance costs” for the utilities, said Go Matsuo, the head of Energy Economics and Society Research Institute in Tokyo. “Could we keep doing this for another 10 years? That’ll be very difficult.”

Read more: Japan Power Crisis Was a Decade in Making and Won’t Go Away

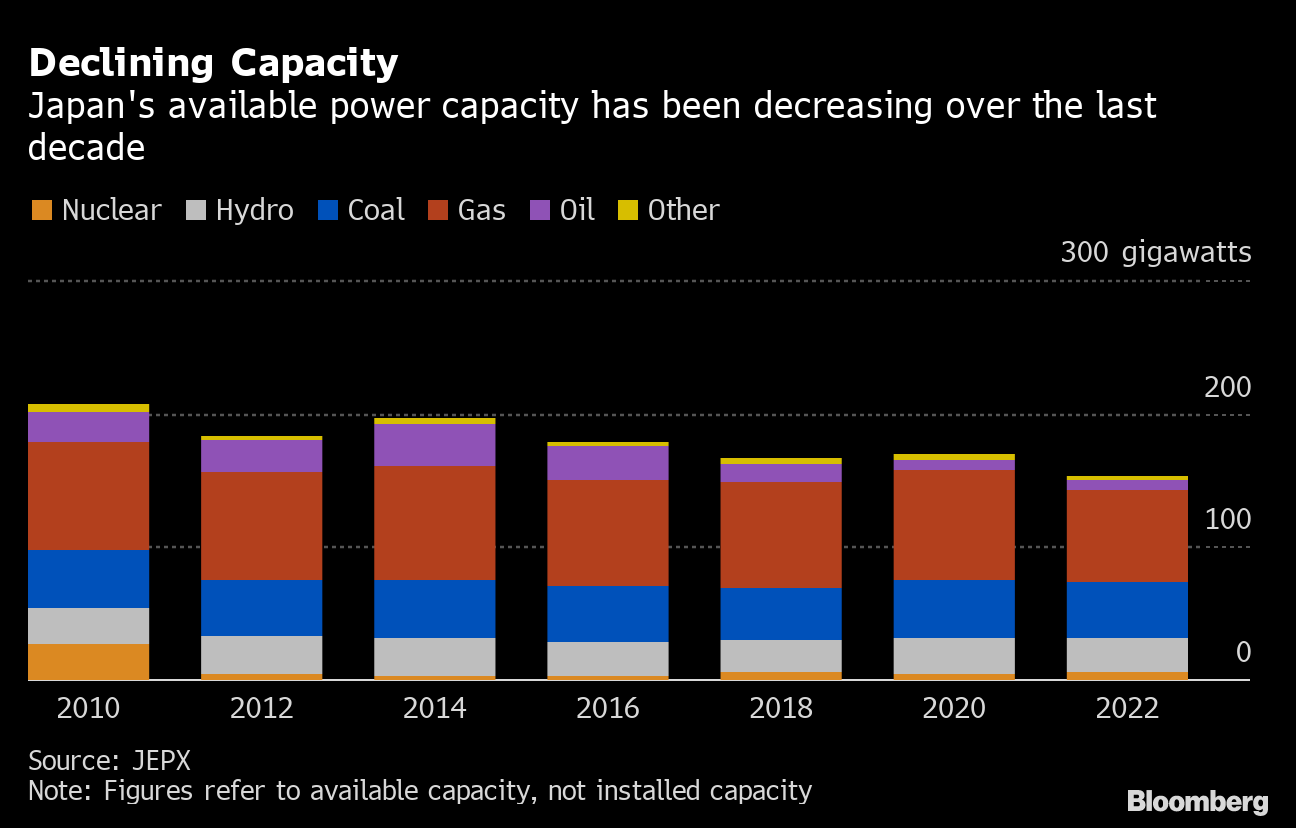

Utilities are expected to eventually retire such thermal power plants amid a push for decarbonization. Over half of the electricity generated in 2021 came from fossil fuel, according to data from the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies. Japan is expected to see a net loss of about 21 gigawatts of liquefied natural gas, coal and oil-fired power capacity between fiscal 2022 and 2031, according to calculations from the nation’s trade ministry.

A key issue is that investment in adding cleaner fuel sources has lagged. Japan, the world’s third-biggest economy, ranked only sixth on spending on the energy transition last year, according to BloombergNEF. The Asian nation invested $26 billion in 2021 compared to spending of $266 billion in China and $114 billion in the US, BNEF data show.

J-Power hasn’t set a strict time limit for Takasago, but has said it wants to gradually phase out aging, domestic coal-fired power plants. In 2018, the company scrapped an earlier plan to replace Takasago's units to bolster capacity to 1200 megawatts, deciding at the time that power demand in the region was on the decline.

Analysts say the economic implications of any possible restrictions on industrial power usage would be serious for Japan’s economy. Kazuki Kitatsuji, a researcher at The Japan Research Institute, estimates that for every percentage drop in power supply for companies, domestic production will fall 961.6 billion yen ($7 billion) annually.

Japan isn’t the only one struggling to balance climate goals with the more immediate need to keep the lights on. This summer’s blazing temperatures have pressured grids everywhere from California to China. India is considering delaying the closure of its aging coal-fired power plants amid rising demand and energy shortage, while European states are mulling delaying the shutdown of their plants in an effort to mitigate gas supply disruptions.

Electricity producers are now eyeing technologies like co-firing with ammonia and hydrogen to lower carbon footprint of their existing power plants — a method J-Power has said it too may adopt.

“There needs to be a serious discussion over how much thermal power source should be maintained” as debate over use of nuclear power and expansion of renewable sources continue, Matsuo said. “This isn’t just Japan-- all countries have to consider this question.”

While public opinion about nuclear energy is still mixed after the Fukushima disaster, the global fuel shortage and recent power crunches have emboldened Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s stance on restarting nuclear reactors. The government aims to nearly double the amount of nuclear reactors on the grid as early as next summer in order to meet the country’s power needs and curb emissions, according to local media.

Read more: Japan’s New Nuclear Push May Not Avert Looming Energy Crunch

Despite the outlook for nuclear restarts and relief over a disruption-free summer, Takasago workers are bracing for a possible power shortage in the winter.

“Summer demand season now stretches from June to September, and in winter, between December to March,” Uchinaga said. “At this rate, demand is high all year long.”

(Updates to add details of Japan’s spending on clean energy in 13th paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

Malibu Firefighters Make Gains on Blaze as Wind Warnings Persist

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture

Blackstone’s Data-Center Ambitions School a City on AI Power Strains

Chevron Is Cutting Low-Carbon Spending by 25% Amid Belt Tightening

Free Green Power in Sweden Is Crippling Its Wind Industry

California Popularized Solar, But It's Behind Other States on Panels for Renters