Banks’ Net-Zero Lending Ambitions Hit Snags in Oil-Rich Canada

(Bloomberg) -- Canada’s banks have only just started on the path toward zeroing-out the carbon emissions of the companies they lend to, and already they’re running into conflicts between what climate activists and ESG investors want and what Canada’s oil-dependent economy demands of them.

Fossil-fuel lending is a tiny part of the loan businesses for many banks outside of Canada that have also pledged to reach net-zero emissions in lending by 2050. They can replace that business with other sources of profit over time.

For Canada’s banks, it won’t be so easy. The country’s five largest banks were among the world’s top 10 fossil-fuel lenders last year, and four of them were among the top 20 arrangers of the sector’s bond issuances.

These banks now find themselves in a similar position as many governments -- under pressure to help decarbonize the economy while also facing domestic obligations to support growth, even if that means doing business with big polluters.

The banks’ ambivalence on climate was on display in their most recent ESG reports. Only one of the Big Five, Bank of Montreal, pledged to reduce the absolute emissions from the most carbon-intensive parts of its loan book by 2030.

Three others -- Toronto-Dominion Bank, Bank of Nova Scotia and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce -- have set softer, so-called “intensity-based” targets that aim for lower emissions per unit of output but still allow for total emissions to grow. Royal Bank of Canada has yet to release its 2030 targets and says they’ll be announced this fall.

On reducing their financed emissions, Canadian banks are “definitely playing catch-up, and that has been true for quite a while,” said Matt Price, director of corporate engagement for the finance sector at Investors for Paris Compliance, which works to hold public companies accountable to their net-zero pledges. “One of the major reasons we’re playing catch-up is because our banks are very exposed to oil and gas.”

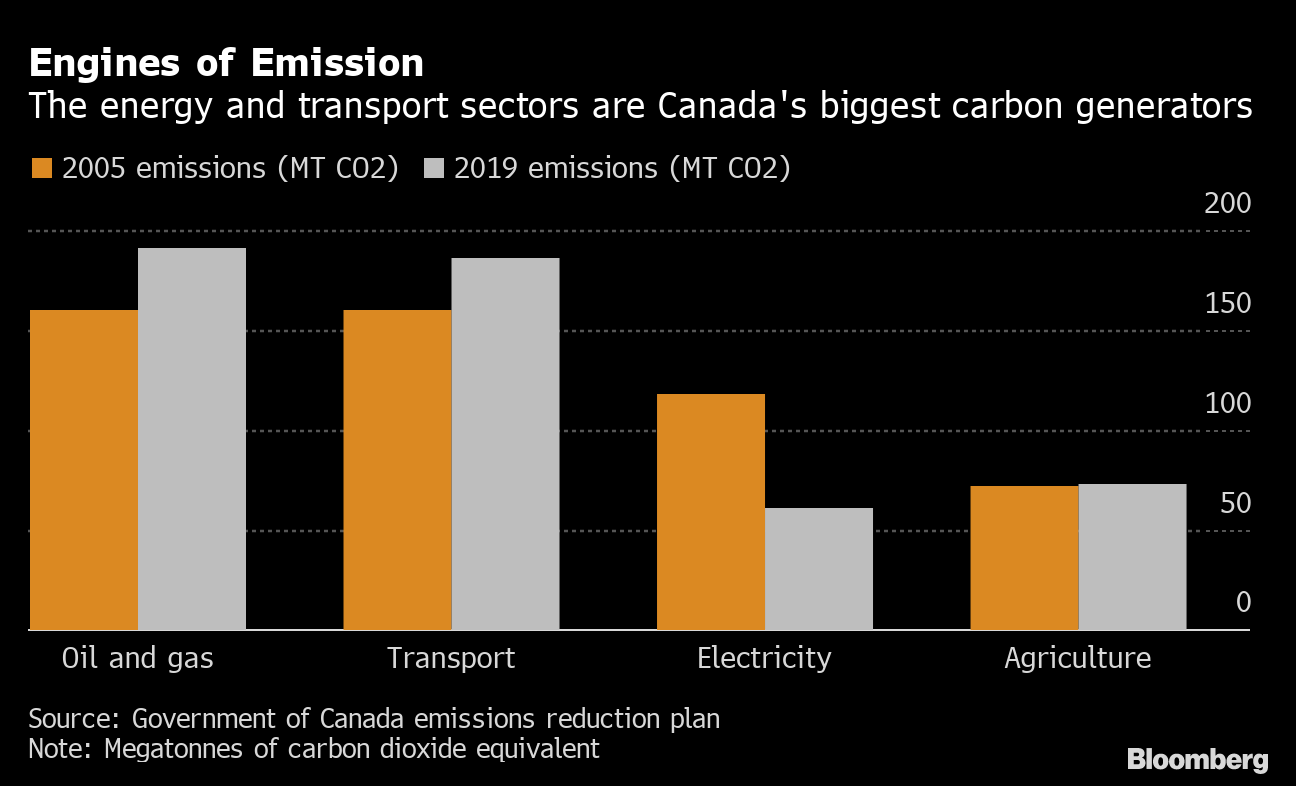

Even with the grip that fossil fuels have on Canada -- the energy sector accounts for about 10% of its economy -- the banks have compelling reasons to make their net-zero promises.

A growing number of institutional investors are cutting fossil fuels from their investment mix as part of the broader social-responsibility movement. Banks’ loan books are also increasingly being scrutinized by climate activists who view fossil-fuel lending as enabling global warming. That’s especially true in Canada, where oil-sands extraction requires some of the most carbon-intensive production processes in the world.

Canadians are also highly climate-conscious. About 71% of them agree that climate change is real and mostly caused by human activities, and half say it’s a “very serious threat,” according to a poll last year.

Strong interim targets for absolute emissions are important because the scientific consensus is that fast and dramatic action is needed to prevent catastrophic climate change. Global carbon-dioxide emissions need to fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

So far, Bank of Montreal is the “clear leader” on ESG, Price said. The lender is aiming for a 24% cut by 2030 from its oil and gas borrowers’ scope 3 emissions, which come from the burning of the fuels the companies sell. The bank is also planning a 33% cut in the intensity of those borrowers’ scope 1 and 2 emissions, which are those generated by their operations and those of their suppliers.

The banks emphasize that they’ll meet their targets not by cutting off fossil-fuel clients but by helping finance these companies’ carbon-reduction efforts. Not only would cutting them off mean sacrificing a large part of their lending businesses; it would also invite scorn among the millions of personal-banking customers in the oil-producing prairie provinces.

Royal Bank, the country’s largest lender by market value, has so far focused on releasing an initial measurement of scope 1 and 2 financed emissions across its entire lending portfolio, “a considerable piece of work,” said Lindsay Patrick, head of strategic initiatives and ESG at RBC Capital Markets. Scope 3 emissions data from the high-emitting portions of its lending portfolio will be released as more and better data become available, she said.

“We wanted to use a consistent methodology, leveraging relatively similar baseline data, to get a very good view of the overall portfolio,” Patrick said. “We really see this as a broader economic transition to net zero, not just within certain asset classes.”

As for the bank’s interim goals, Chief Executive Officer Dave McKay strongly suggested they’ll target absolute emissions, which he said “are the only ones that really count over time.”

“There’s more complexity to setting absolute reduction targets, and we’re just taking a little bit more time,” McKay said in response to reporters’ questions after the bank’s annual meeting on Friday. “And in a 10- and 30-year journey, does two months make a big difference?”

Scope 3 emissions from the fossil-fuel industry are the most important metric because they capture the burning of the fuels that oil companies produce, which account for most emissions, Price said. Many global banks, including HSBC Holdings Plc and Barclays Plc, have already started making those figures public.

Similarly, many global banks have set absolute emissions targets. Citigroup Inc. has committed to a 29% absolute reduction in financed emissions for the energy sector by 2030, while Barclays plans to cut the total emissions of its energy portfolio by 15% by 2025.

Oil Sands Plans

The Canadian banks’ ability to meet their targets will depend on the oil-sands industry’s own efforts to get cleaner, which rely heavily on expensive technology to capture carbon before it’s released into the atmosphere. Canada’s federal government said recently that it’s seeking a 42% reduction in oil and gas sector emissions by the end of the decade.

The oil-sands industry’s plans to be net-zero by 2050 are “quite achievable,” with help from policies like the Clean Fuel Standard and higher carbon prices, said Jackie Forrest, executive director of the ARC Energy Research Institute in Calgary. But the near-term targets to cut emissions by about a third by 2030 may be harder to meet, she said.

“To build a massive CO2 pipeline and all the infrastructure to store carbon and to capture it -- that’s a long project,” Forrest said. “It’s a little more uncertain how much can be done in the 2030 timeframe.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture