California Nimbys Threaten Biden’s Clean Energy Goals

“Everyone here is in favor of green energy,” O’Brien said.

But that support has its limits. When he learned of plans to build a giant solar farm next door to his property—the kind of project that would help meet the state’s clean energy goals—O’Brien decided he had to fight it. It was exactly the sort of thing that would spoil the rural landscape that he says should be protected by a local anti-development measure.

“It would be a sea of glass,” said O’Brien. “It disturbs the environment.”

O’Brien is part of a group of ranchers, farmers and environmentalists who oppose what would be the largest solar plant built in the San Francisco Bay Area. The clash offers a preview of potential disputes that could slow the ambitious push by California and the Biden Administration to develop clean energy to combat climate change.

The Aramis Renewable Energy Project, developed by Intersect Power, would cover about 350 acres of private pastureland with close to 229,000 eight-foot-high solar panels that can generate 100 megawatts of carbon-free electricity, or enough to power 25,000 homes annually. The proposed site, which will also include battery energy storage, is about 50 miles east of San Francisco.

“Anyone who understands the scale of the climate crisis knowns we need to go faster and we need to build at a much larger scale,” said Carlo De La Cruz, a deputy regional director for the Sierra Club, which supports the Aramis project. “California is one of the most progressive states when it comes to climate policies, but we still need to build more clean energy to meet our climate targets.”

Opponents of the project, including a group O’Brien chairs called Save North Livermore Valley and the Ohlone Audubon Society, recently sued the county of Alameda, which approved the solar farm earlier this year, saying that the renewable energy facility would violate a voter-approved measure designed to protect open space, agriculture and wildlife habitat. Some of the same citizen groups also opposed a separate, smaller nearby solar project that was recently canceled by another developer.

“We moved out here 25 years ago, and one of the reasons we did is the zoning only allows one house for 100 acres,” O’Brien said, as he looked out into a valley of pastureland dotted with oak trees and rusted-out barns and ranch homes. “There is nothing in the zoning or general plan that permits this type of use.”

Biden has set an ambitious target of ridding carbon from the U.S. grid by 2035. To meet its goal of a carbon-neutral grid by 2045, California will need to triple its annual solar and wind installations, according to a recent state study. That means the state may need to develop as much as 3.1 million acres—almost as large as the state of Connecticut—for solar and wind projects by the middle of the century, according to a different report by the Nature Conservancy.

While solar and wind farms don’t come with environmentally damaging fossil-fuel extraction and the polluting smokestacks of coal and natural-gas plants, they generally require more acres to develop. Land can be farmed around wind turbines, but that’s trickier with solar plants.

And some of the new clean energy projects will likely need to be built closer to the cities and towns that will use the power.

The authors of the Nature Conservancy report found that many areas in the U.S. West both have high renewable energy resource potential and high conservation values, setting up the potential for conflicts. Future disputes can be avoided with early planning and mapping of locations where large scale solar and wind can be built with the least environmental impact

Already, renewable energy developers and conservationists have clashed over utility-scale solar energy projects across the U.S. Southwest. In the Mojave Desert, residents and local environmental activists are fighting against big solar plants, raising concerns that the facilities would spoil the fragile landscape and imperil threatened species like the desert tortoise.

Locals upset about solar panels carpeting the desert floor prodded San Bernardino County, located northeast of Los Angeles, to ban in 2019 construction of renewable energy projects in certain areas.

In Alameda County, the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the Aramis solar plant in March after a contentious eight-hour meeting, saying it will help meet local clean energy needs. The county found that the project’s benefits outweighed the environmental impacts.

“When it comes to climate change, it seems that trumps open space in terms of the analysis in my mind,” Supervisor Nate Miley said of his support of the project during the meeting.

Intersect Power Chief Executive Officer Sheldon Kimber said the company’s project has gotten all the necessary government approvals and has received “an enormous amount of support” from local political leaders, businesses, residents and environmental groups.

Kimber said the lawsuit won’t impact the timing of the project, with construction slated to start by the middle of next year with an operating date of the middle of 2023. The case, however, has yet to have a briefing or a hearing, according to Robert Selna, an attorney representing Save North Livermore Valley.

The company has inked contracts to sell the solar power to public-run power agencies in Alameda County and San Francisco, helping them achieve their clean energy goals, Kimber said. It will create about 400 local temporary union construction jobs.

To mitigate environmental concerns, the solar panels will be set back from a local creek and avoid federally designated habitat for the threatened California red-legged frog. The company says it will dedicate land for a hiking trail along the creek as well.

In addition, the site will be shielded from the road by drought-friendly landscaping and provide open spaces for sheep grazing and bee keeping in what the company calls a model for “agrivoltaics” – marrying agriculture with solar.

“Realistically, the only concern we haven’t mitigated is ‘we just don’t want it here,’” said Kimber. “Those minority voices try to scare people, saying companies like mine are going to just blanket California with solar. And the reality is, that is preposterous.”

Opponents, however, remain undaunted. Save North Livermore Valley, the group of about 400 ranchers, farmers and other local citizens that includes O’Brien, has set up a GoFundMe to help raise money for its litigation fight (so far, they’ve raised $39,740 of their $95,000 goal).

Selna, the attorney representing the group, said the county should have anticipated opposition. He said the dispute may have been avoided if the county had completed a plan to designate areas where solar would have the least impact on the environment and threatened species. The GoFundMe account represents a "small fraction" of the amount that the group has raised, Selna said.“The Aramis project is a cautionary tale for local governments who want to support solar,” Selna said.

Bart Broadman, who owns about 110 acres of the site for the solar farm, said he felt like the project was the “highest and best” use for land that has marginal agriculture value because of a lack of water.

"There is handful of neighbors and folks who are primarily concerned, it seems, to preserving their views of open space,” Broadman said. “That strikes me as a bit selfish at time when you see California burning up and climate change driving drought.”

(Updates story with details of the county's approval in the 16th paragraph. An earlier version company corrected the number of panels in the sixth paragraph and details of hiking trail in the 21st paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

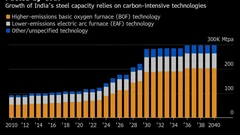

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture