Houthi Hit on Russian Fuel Has Traders Recalculating Risks

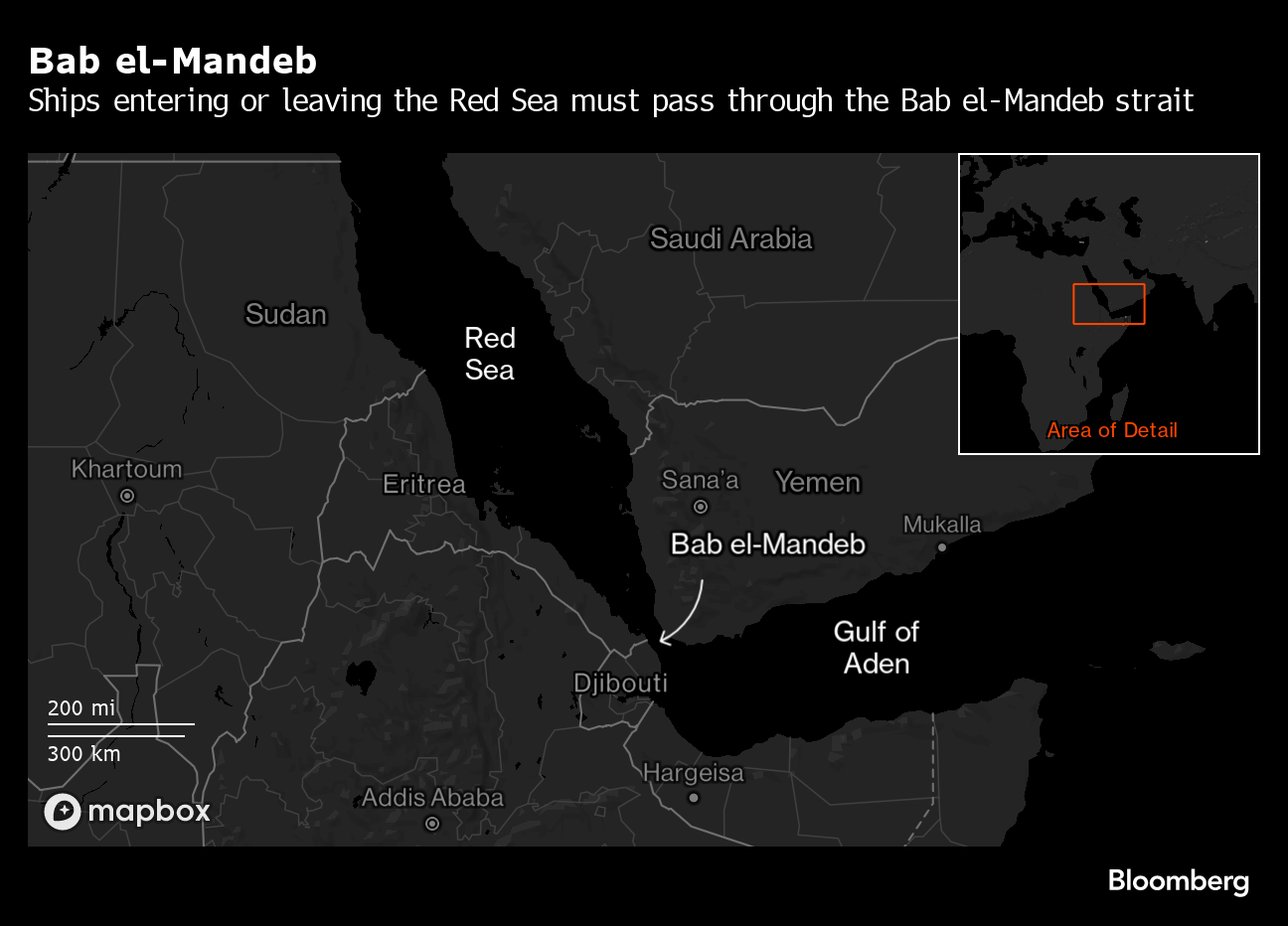

(Bloomberg) -- A missile attack on Friday on a tanker taking Russian fuel through the Gulf of Aden may prove to be a defining moment for an oil market that had previously been somewhat immune to months of Houthi militants’ attacks on merchant trade.

Why the calm? Because much of the oil flowing through the Red Sea and Suez Canal came from Russia and — so the theory went — it might be safe. The Houthis themselves signaled Russian ships had nothing to fear, and Moscow is an ally of their sponsor Iran. Oil tankers generally had been largely spared.

But Friday’s attack made one thing clear: whatever assurances Yemen’s Houthis offer, they don’t extend to a ship’s cargo if the vessel itself has even a tenuous link to the US, UK or Israel. The Houthis had said they were targeting Israeli assets because of the war in Gaza, and then extended their reach to US and UK vessels after those countries launched airstrikes in Yemen.

The attack means that a greater slice of the 3 million barrels a day of Russian crude oil and fuel that has been flowing through the Red Sea to reach customers in Asia could be at risk. And Russian volumes matter to the global market — despite sanctions imposed because of Moscow’s own war in Ukraine.

Risks were heightened further after the US said Iran-backed proxies struck a base in Jordan over the weekend that killed three American soldiers, intensifying pressure on President Joe Biden to respond. Iran said it had “no connection” with the attack.

With crude prices popping about $2 higher on Friday, and rising again on Monday, here are some of the questions that oil traders will be considering when they return to their desks this week.

Will Red Sea Transit Stop?

This is unlikely, either for trade in general or to the flow of petroleum in particular.

The decision to transit depends mainly on four things: the willingness of the owner, that of the crew and the charterer — and profit.

If a charterer wants to go through the Red Sea and finds a shipowner who’s willing, with a crew that’s prepared to run the gauntlet — perhaps for extra danger money — then the trade will happen as long as the price makes sense.

It’s true that insurance costs can be so prohibitive that some owners find it more attractive to go the long way around Africa — following container shippers that have already made that call. But, while Friday’s attack redefined the kinds of ships that might be viewed as targets, not all ships will fall into that category. The most likely outcome is that the numbers willing to risk it thins out, but the route doesn’t shut altogether.

Is All Russian Oil Now a Target?

Probably not. The international maritime database Equasis lists the manager of the Marlin Luanda — the tanker that got attacked — as a firm called Oceonix Services Ltd. in London. For the Houthis, that may have been enough of a link.

But the fuel on the Marlin Luanda was different to a lot of Russian petroleum in one crucial way: it was being hauled using western service providers as it was priced within the cap allowed by US sanctions.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the sanctions that followed, most Russian oil and fuel is being moved on the so-called shadow fleet. These vessels have secretive ownership structures, almost never have published UK, US or Israeli links, rarely if ever go to those countries’ ports, and even their insurance is opaque.

If the Houthis are profiling their targets using open-source intelligence, there will still be a lot of Russian oil they don’t go after, at least in part because there is so little information available publicly about those ships. Russia is an ally of Iran, which backs the Houthis, and Moscow has condemned US and UK strikes on Yemen.

Still, there’s always the risk of getting caught up in a misfiring, or becoming collateral damage.

Will Insurance Costs Rise?

Probably. Even before the Russian fuel cargo was hit, the cost of insurance for transit had jumped tenfold in a few weeks to about 1% of the value of a ship’s hull.

That’s as much as about $1 million for some vessels, potentially more than their additional fuel bills to sail around Africa instead.

Shortly after the US and UK bombed Yemen to try to quell the Houthi attacks, analysts at Clarksons Securities said that the rising cost of insurance could start to make more ships take the detour.

What Will Owners and Crews Think?

This will likely prove the biggest question of all for the global oil market, but it will take some time to get a clear picture because what matters most is how the owners linked to Russia behave.

Some mariners were clearly nervous well before the Houthis set the Marlin Luanda alight, and many mainstream international owners were already diverting. Even before Friday, about three quarters of the world’s top tanker owners already appeared to be staying away.

The owners of tankers moving Russia’s cargoes and their crews appear to have been more willing to navigate the area, at least before Friday’s incident.

If that were to change, it would be bad news for Moscow and a potential supply issue for the global oil market.

More of Russia’s oil would have to sail the long way around Africa, straining a tanker fleet that is already starting to look a little stressed due to a ramp up in western sanctions.

Higher oil delivery costs would ultimately hit the price of Russian oil and fuels at the point at which it is exported. And it is not clear by any means that there would be enough vessels if most — or all — had to go the long way around Africa.

(Updates with attack on US base in the fifth paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More oil news

Asian Stocks Fall as China’s Confab Disappoints: Markets Wrap

China’s Weak Winter LNG Demand Provides Relief for Rival Buyers

Oil Edges Higher Ahead of US Inflation Figures and OPEC Report

Oil Slips as Glut Outlook Outweighs Optimism on China Stimulus

Oil Edges Higher as Traders Weigh Fallout From Syrian Upheaval

China’s Solar Industry Looks to OPEC for Guide to Survival

Five Key Charts to Watch in Global Commodity Markets This Week

Oil Steadies as OPEC+ Opts Again to Delay Plan to Restore Output

NMDC LTS to acquire 70% equity stake in Emdad