A Deep Freeze This Winter Hinges on La Nina and the Polar Vortex

(Bloomberg) -- Nobody controls the weather, and yet temperatures this winter will ripple through every conceivable market, from fuel to food, with a particularly frigid outcome threatening to turn a worldwide energy crunch into a full-blown crisis.

The stakes have never been higher. If the weather’s bad, households and businesses around the world, already facing the heftiest energy costs in years, could face crippling heating bills. Governments struggling to ease fears of inflation could lose popular support. And the clean energy transition, already under fire after low wind generation helped contribute to Europe’s power shortage, could be thrown even further into question.

Every meteorologists’ long-term forecast is frustratingly different, given how hard it is to accurately predict the winter’s bite when summer just ended. But projections share some features: The emergence of a La Nina could bring colder weather to the northern U.S. and milder climates in the south while drying out other parts of the world. At the same time, the polar vortex that contains icy air above the North Pole appears weaker than last year. That means there’s a greater chance that frigid cold will occasionally spill out of the Arctic into the temperate zones of Asia, North America and Europe, bringing intermittent chilling effects throughout the season.

“We expect a ‘warm sandwich’ this heating season with a potentially very cold center,” said Todd Crawford, director of meteorology at commercial-forecaster Atmospheric G2. That could mean an unusually warm start to the season, then a cold period into January, followed by a mild end of winter and an early spring. “These expectations are broadly appropriate for all major energy-demand centers in eastern U.S., western Europe and northeast Asia.”

Of course, these are only forecasts, and early ones at that. There are a multitude of interrelated weather patterns and factors that will determine the fate of this winter, and scientists don’t even agree on which will be key. Here are some of the main phenomena that meteorologists are closely watching to make their predictions, and a look at what they’re signaling so far:

La Nina and the Pacific Ocean

A weather-bending phenomenon that twists atmospheric patterns, La Nina threatens to rear its head for the second straight year.

When a La Nina forms, upending storm patterns across North America, it usually brings cooler weather across the U.S.’s Pacific Northwest and upper Great Plains, while drying and warming the southern part of the country. These formations also conspire to drive weather patterns the world over, potentially chilling Japan and Korea, bringing drought to Brazil and Argentina, and drying out parts of China. The phenomenon is so large, it will play an underlying role in many seasonal forecasts. The U.S. Climate Prediction Center says there is a more than 70% chance that cool waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean will trigger the phenomenon.

Back-to-back La Ninas aren’t unheard of—they’ve happened eight times since 1950. The problem for forecasters is they don’t always impact climate the same way. Last winter, La Nina brought a relatively mild winter to the Northern Hemisphere, but this year’s pattern could be different.

La Nina isn’t the only tremor in the world’s largest ocean that’s drawn attention. Stretching west from British Columbia across the North Pacific is a large pool of warm water that’s sometimes called—no fooling—“the blob.” La Nina and the blob “both favor dry conditions for western states, which is horrible news,” said Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist with the Woodwell Climate Research Center. That means the potential for “ongoing drought and fires.”

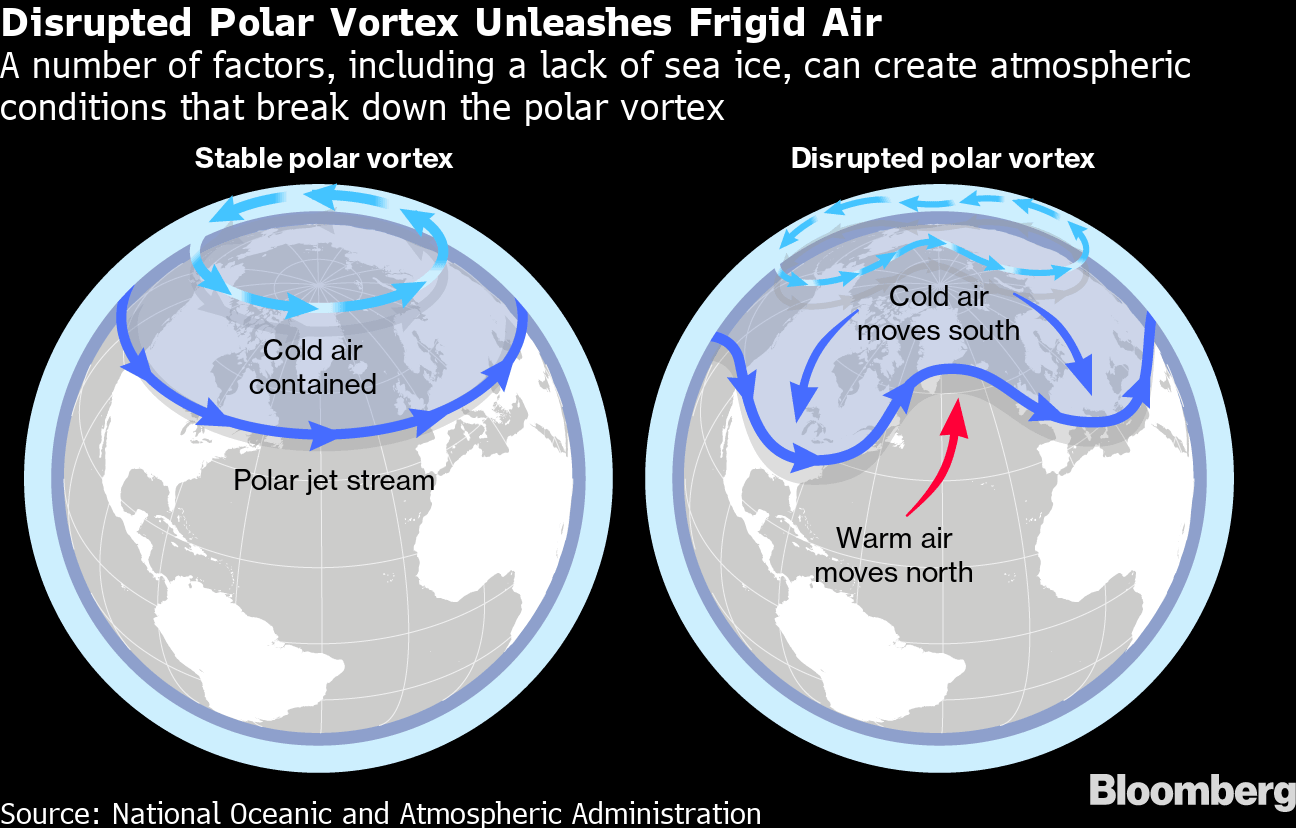

Polar Vortex Disruption

Tilted away from the sun’s warmth for months on end, the North Pole builds a reservoir of some of the Earth’s coldest air during winter. A girdle of winds called the polar vortex spins around the top of the world, locking that cold air up tight. If it escapes the confines of the Arctic, parts of Asia, Europe and North America will be blasted with bursts of cold, driving demand for heat.

Meteorologists weighing the likelihood that the polar vortex weakens and lets the cold out are watching indicators like the accumulation of sea ice and sudden stratospheric warming, two early signs of disruption. Such a warming over the North Pole in the stratosphere—a layer in the atmosphere that stretches from about 5 to 30 miles (8 to 48 kilometers) above the earth—happens in about 55% to 60% of winters, Crawford said. It can have disastrous effects: It was a sudden stratospheric warming last January that ultimately resulted in the historic cold that slammed the Southern U.S. the following month, crippling the Texas electric grid and killing at least 210 people.

If the cold does drop out of the Pole, the big question becomes where it will go, since it can’t chill all parts of the Northern Hemisphere at once. A key factor is often the North Atlantic Oscillation, a shifting pattern of high and low pressure over Greenland and the ocean. If the oscillation is in its negative phase, high pressure blocks station themselves over Greenland, slamming the atmospheric flow from North America shut and usually leading to cold—and sometimes stormy—weather in the U.S. Northeast.

It can also shift the storm track over Europe to the south, leaving the northwestern Europe quite chilly, said Tyler Roys, a meteorologist with AccuWeather Inc. The colder Europe gets, the worse its energy crunch will be. If a so-called blocking pattern sets up over the Gulf of Alaska, it can create a pump of cold air into the heart of the U.S., said Jim Rouiller, lead meteorologist at commercial-forecaster Energy Weather Group.

Siberia and the Urals

For Judah Cohen, director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research, part of risk analytic firm Verisk, one indicator worth scrutinizing is Siberian snow. While not everyone subscribes to this theory, Cohen believes that if snow rapidly accumulates across Siberia in October, it can create conditions that will eventually trigger a disruption in the polar vortex. Scientists will know more about how this metric is shaping up at the end of the month.

He’s also closely watching the formation of high pressure areas in the Scandinavian-Urals region as an indicator. If such a pattern persists “into November and especially December, a significant disruption of the polar vortex this winter is almost inevitable,” he said.

Francis at Woodwell is watching the same area for signs. “Some models are hinting at a weakened vortex, which often opens the ‘refrigerator door’ and allows cold air to spill southward over North America and Eurasia,” she said. “Could be an early winter for lots of folks if that happens.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More oil news

Wall Street Weighs ‘Hawkish Cut’ While Tech Shines: Markets Wrap

Oil Rises as Possible Iran, Russia Sanctions Temper Glut Outlook

China’s Weak Winter LNG Demand Provides Relief for Rival Buyers

Oil Edges Higher Ahead of US Inflation Figures and OPEC Report

Oil Slips as Glut Outlook Outweighs Optimism on China Stimulus

Oil Edges Higher as Traders Weigh Fallout From Syrian Upheaval

China’s Solar Industry Looks to OPEC for Guide to Survival

Five Key Charts to Watch in Global Commodity Markets This Week

Oil Steadies as OPEC+ Opts Again to Delay Plan to Restore Output