Lenny Bruce’s Lawyer Mounts Quixotic Defense of Chevron Foe

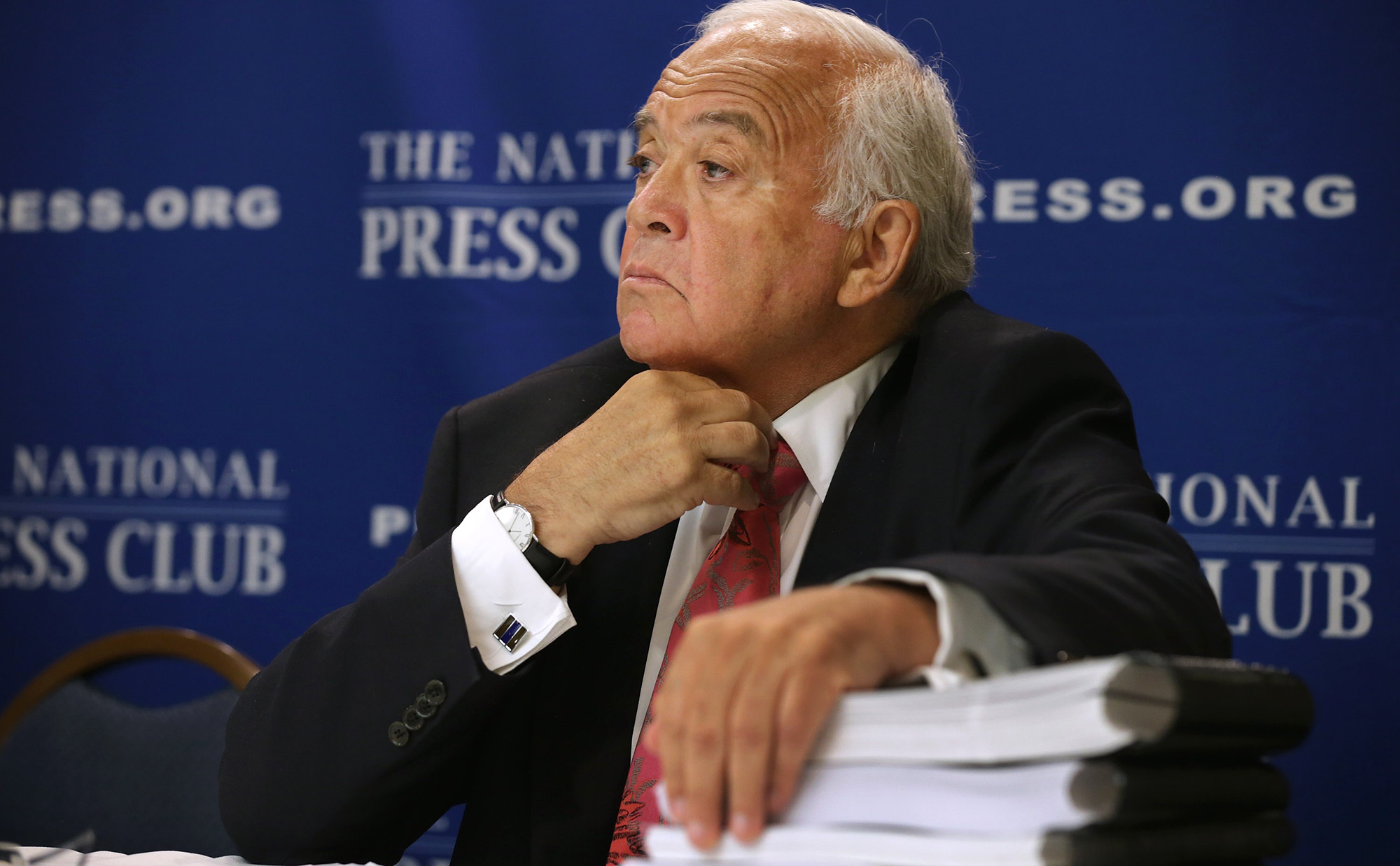

(Bloomberg) -- In his six decades as a crusading lawyer for free speech, Martin Garbus has represented Lenny Bruce, Daniel Ellsberg and Nelson Mandela. So why, at 86, is he waging a quixotic battle for a disbarred attorney charged with a misdemeanor?

His answer: “There’s never been a case like this.”

Garbus is defending Steven Donziger, 59, who is charged with criminal contempt of court for failing to follow a judge’s orders. Donziger’s legal team won an $8.6 billion judgment against Chevron Corp. in Ecuador in 2011 after a decades-long battle over pollution in the Amazon rainforest. But three years later U.S. District Judge Lewis Kaplan ruled that Donziger had secured the huge award through fraud and blocked him from collecting it in the U.S. The judge ordered him to turn over evidence to Chevron, along with his right to more than $550 million in legal fees.

Donziger believed it would be wrong to hand over privileged information, and his intention wasn’t to defy the court, Garbus said at Donziger’s trial this month.

In an interview, Garbus said the trial wasn’t fair and that Donziger’s conviction is a foregone conclusion. But he said the case was too important to turn down, and too interesting: After federal prosecutors declined to pursue contempt charges against Donziger, the judge appointed outside lawyers to do it for them—a highly unusual maneuver. Garbus blasted the move at Donziger’s trial and thinks it could help propel the case to the Supreme Court.

“It’s to enable lawyers like Donziger to think there’s some kind of protection for what they do,” he said of the reason he took on the case. “It’s for people to think they can litigate against giant companies like Chevron.” At the trial, he opened with a remarkable assertion, and one that suggests an aggressive appeal if his client is found guilty.

‘She Will Send Him to Jail’

“Deprived of a jury of his peers, Donziger faces near-certain conviction by way of a private prosecutor responsible to no one,” Garbus told U.S. District Judge Loretta Preska, who will decide the case. The non-jury trial ended on May 17. Donziger faces a jail term as long as six months if convicted.

“She will send him to jail,” Garbus said of Preska, whom he had accused of bias in a court filing that unsuccessfully sought her recusal.

His co-counsel on the case is Ronald Kuby, a well-known civil rights attorney himself who worked closely with the famed radical lawyer William Kunstler. Kuby called Garbus “one of those great, towering luminaries of that generation of lawyers.”

Donziger’s long struggle with Chevron became a rallying cry for environmentalists and celebrities, and his criminal prosecution has ignited renewed outrage, spurring a letter from Nobel laureates demanding the case be dismissed. The defense held rallies outside the courthouse in lower Manhattan, where supporters including the actor Susan Sarandon and Roger Waters of the band Pink Floyd wore masks reading “Free Donziger”—as the defendant himself did during the trial. Some waved Ecuadorian flags, while others wore kangaroo masks to say the trial was a farce.

“Chevron is not a party to the criminal case, did not initiate the criminal charges, and played no role in the court’s decision to charge Donziger with criminal contempt or appoint the special prosecutors,” spokesman Jim Craig said in a statement.

‘Not the Warren Court’

Some of Garbus’s efforts in court seemed calculated to provoke Preska, who has kept her cool. Outside court after the trial, Garbus compared the case to his experience with trials in China.

“After the case is over, after the judge has heard the case, you take a break,” he told a reporter. “And the purpose of the break is to allow him to speak to the political people, who will then tell him how to rule. And what happened here is not dissimilar.”

Garbus isn’t sure about Donziger’s prospects before the Supreme Court, if the case ever gets there.

“If this was a Warren court, we would win,” he said, referring to the liberal high court of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who presided in the early days of Garbus’s career. “It’s not the Warren court.”

Reflecting on the case, Garbus said that at this point in his career he can “do things that are more difficult for other lawyers” because “I’m relatively impervious. People have already tried to disbar me—the South African government a long time ago.”

Garbus was born in Brooklyn a. After losing most of his family in the Holocaust, his father tried to teach him to keep his head down. Garbus did the opposite, telling his own children to fight for their right to speak out.

His defense of Donziger, without a legal fee, reflects a career spent taking on unpopular causes and vulnerable clients. In the ’70s he spoke out for American Nazis’ right to march in Skokie, Illinois.

He considers his work on Goldberg v. Kelly, a 1970 Supreme Court ruling that established the right to a hearing before states could cut off welfare payments, his greatest accomplishment. After retiring from the bench, Justice William Brennan called Goldberg one of the most important decisions of his career. Garbus said he had hoped the case would help bring about racial and economic equality but that the direction of the high court since then has been “all downhill.”

he years have taken their toll. Garbus withdrew from the case for several months, citing his health and the pandemic, and Kuby handled the bulk of the trial work.

Sparring With the Judge

Yet at an age when most lawyers have long retired, or at least sworn off the rigors of trial work, there was Garbus in court, arguing before Preska, a senior judge appointed by former president George H.W. Bush in 1992. In his opening, he tried several times to raise issues she batted down.

“Why did Judge Kaplan, after the prosecutor said no, make his own decision to elevate a civil discovery dispute that could be resolved by appellate review into a criminal case?” Garbus asked.

Preska struck much of the argument from the trial record.

“Mr. Garbus, this has nothing to do with the charges,” she said.

“We disagree,” Garbus said.

“Well, I’m sorry to tell you,” the judge said, “but I’m the guy who decides here.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More oil news

Wall Street Weighs ‘Hawkish Cut’ While Tech Shines: Markets Wrap

Oil Rises as Possible Iran, Russia Sanctions Temper Glut Outlook

China’s Weak Winter LNG Demand Provides Relief for Rival Buyers

Oil Edges Higher Ahead of US Inflation Figures and OPEC Report

Oil Slips as Glut Outlook Outweighs Optimism on China Stimulus

Oil Edges Higher as Traders Weigh Fallout From Syrian Upheaval

China’s Solar Industry Looks to OPEC for Guide to Survival

Five Key Charts to Watch in Global Commodity Markets This Week

Oil Steadies as OPEC+ Opts Again to Delay Plan to Restore Output