The Money Food Badly Needs for Climate Fight Is Rolling In

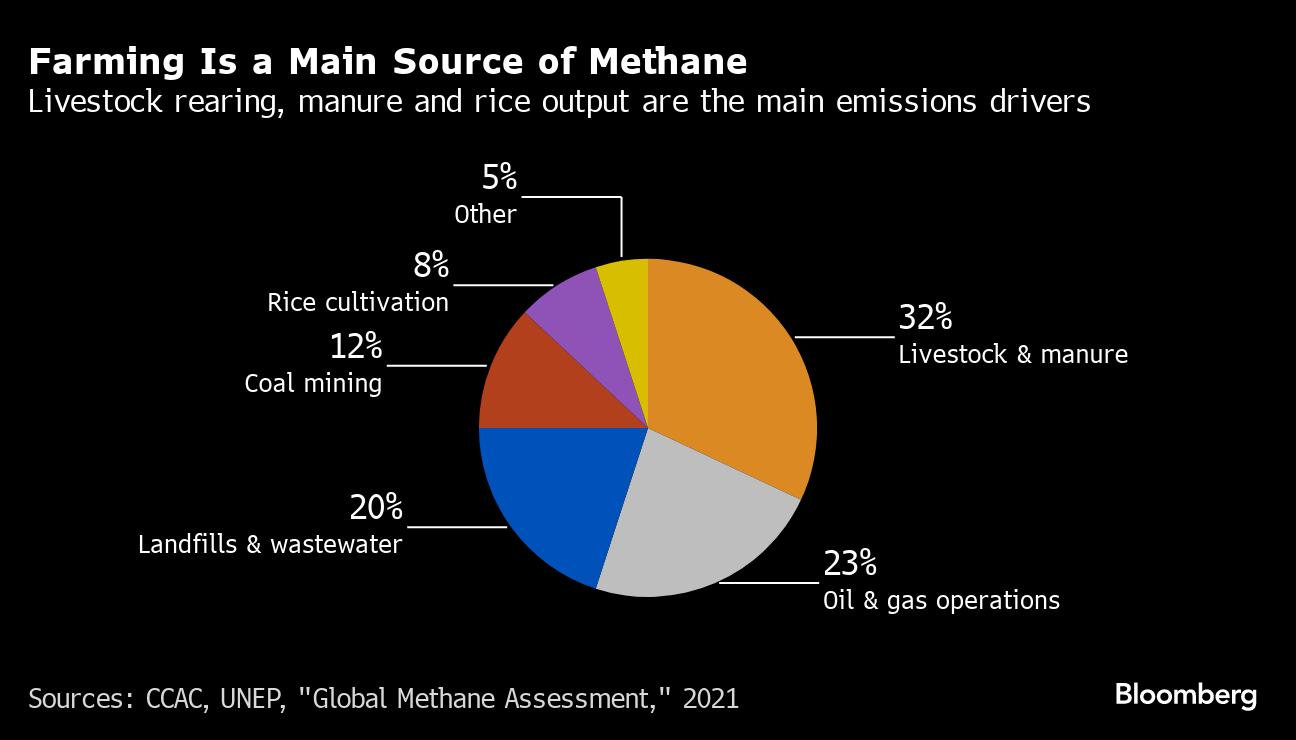

(Bloomberg) -- Supercharging crop seeds to better withstand drought. Breeding cows that burp out less methane. And tracking cattle to prevent deforestation.

They’re part of the arsenal the world needs for food’s contribution to the climate fight, and they’re getting a big cash boost.

More than $3 billion in climate finance has been pledged for food and agriculture since the start of the COP28 summit in Dubai, according to the organizers. On top of that, governments, philanthropies and private money are boosting funding for tackling methane in agriculture, ending deforestation, and climate-smart innovation, as the summit finally puts what the world eats higher on its agenda.

Ensuring the food system limits and better copes with climate change is key to hitting green goals, especially as populations grow. From farm to fork, food makes up about a third of greenhouse gas emissions, while also being increasingly threatened by rising temperatures, erratic weather and changing rain patterns. More money will help speed up technologies and strategies needed for the battle.

“Even if you were able to fix the just energy transition and go completely renewable, you still wouldn’t be able to reach the 1.5 degrees if you don’t solve the food systems issue,” Mariam Almheiri, the United Arab Emirates minister for climate change and the environment, said in an interview. “That’s how big of a cause this is. Food systems will now be center stage in all future COPs.”

COP’s official tally for food project funding doesn’t include certain other related announcements over the past couple of weeks, such as the $10 billion Africa and Middle East SAFE Initiative, a public-private project officially launched on Dec. 3 to advance climate-smart agriculture. A group of philanthropic organizations on Sunday pledged an extra $302 million for food’s climate transition.

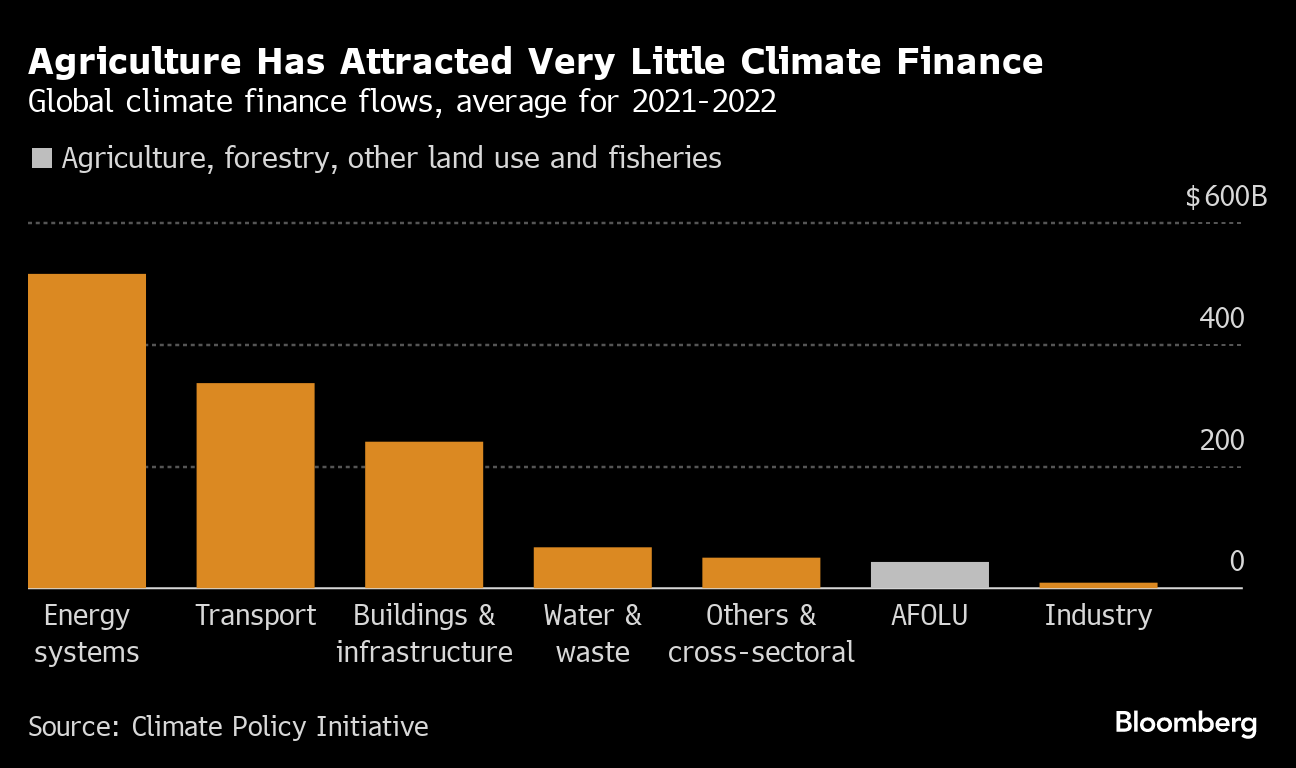

The pledges still need to be followed with real money and action. Financing has for years lagged the amount pouring into many other sectors and the gap for what agri-food needs is “huge,” said Barbara Buchner, global managing director at the Climate Policy Initiative.

The challenge is massive. The last three decades saw $3.8 trillion of crops and livestock production lost due to disasters including floods and droughts, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization says. But beyond such headline-grabbing events, there lurks a slow and dangerous worsening of conditions for millions of farmers around the globe.

In India’s Chhattisgarh state, farmers Lal Singh Rathore and Narayan Singh have seen soil gradually harden and get more depleted, while pests and diseases have multiplied. Argentinian honey maker Ana Laura Sayago’s bees have struggled to get enough nectar as dryness stops flowers blooming and hives melt in heat. And in Uganda, Elizabeth Nsimadala’s avocado seedlings were destroyed by prolonged drought.

“You prepared for just one month of drought and then you experience almost three-and-a-half months,” said Nsimadala, who came to Dubai to push for change. “Climate change is upending farmers’ livelihoods on a massive scale. It has really affected each and every farmer. We need drastic actions.”

Many food experts hailed this year’s COP for bringing more attention to the issue. Some 140 nations signed a declaration during the summit vowing to include food and agriculture in their climate plans, and more than 130 recognized the need to shift to sustainable healthy diets. Ultimately those signatories will need to produce real strategies for achieving their pledges. More than 200 companies and organizations have called for time-bound global targets by COP29.

“This has been an unprecedented COP for food and climate, the COP when food came of age as a central means of responding to the climate emergency,” said Edward Davey, partnerships director at the Food and Land Use Coalition. “Now the onus is on all of us to hold ourselves accountable for the commitments made.”

Sunday marks Food, Agriculture and Water Day at COP, the first ever dedicated entirely to food systems — which include everything from how food is grown and processed to how it’s distributed, eaten and in many cases wasted. The UN’s FAO also unveiled a first comprehensive plan to bring the global industry in line with the Paris climate agreement.

Here are some key investments and food announcements during the summit:

Greener Cows and Saving Forests

Much of food’s climate footprint is linked to livestock, and more money is backing technologies and research on how to reduce methane they burp out. The Bezos Earth Fund is investing in wearable sensors that measure how much cows emit. Along with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, it’s also among backers putting some $200 million into a program for breeding low-methane animals and developing less potent feed additives.

Bloomberg’s latest newsletter highlights how diary giants like Nestlé SA and Danone have committed to disclose methane emissions within their supply chains, an important step for the private sector. It also mentions how Brazil’s Para state is creating a traceability system, which should discourage purchases of cattle reared on deforested land.

Seeds, Soil and Family Farms

Small-scale farms produce a third of our food, but get just a sliver of climate funding. At COP28, smallholders in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia secured $200 million in pledges from the Gates Foundation and the United Arab Emirates to help adapt to climate change.

There’s also a push for more climate-smart solutions, from using microbes that boost carbon in soil to turning organic waste into protein-rich feed. A US-UAE initiative called Aim for Climate wants governments and companies to invest more in those kind of areas and has seen investments of more than $17 billion, up $4 billion since May.

One startup in its network is Mati Carbon Removals, which removes carbon by spreading rock powder on rice paddies in India. Another linked project is a US initiative working to improve soils and identify the most nutritious crops in Africa so they can be adapted for climate change.

“What we’re trying to do is to get back to basics,” said Cary Fowler, US special envoy for global food security. “We’re not going to have food security in this world unless we have good, fertile, healthy soils and crops that are adapted to the environment.”

(Updates with extra funding in 6th paragraph, call to action in the 11 paragraph.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More gas & LNG news

Tesla-Supplier Closure Shows Rising Fallout of Mozambique Unrest

UAE Names Former BP CEO Looney to New Investment Unit Board

Oman Will Seek Talks With BP, Shell to Secure Latest LNG Project

GE Vernova Sees ‘Humble’ Wind Orders as Data Centers Favor Gas

China’s Oil Demand May Peak Early on Rapid Transport Shift

Qatar Minister Calls Out EU for ESG Overreach, Compliance Costs

Chevron Slows Permian Growth in Hurdle to Trump Oil Plan

After $2.5 Billion IPO Haul, Oman’s OQ Looks at More Share Sales

ADNOC signs 15-year agreement with PETRONAS for Ruwais LNG project