India Overhauls Nuclear Law to Allow Private Investment

(Bloomberg) --

India’s parliament passed a bill that will open up its nuclear industry to private firms and unlock investment opportunities worth $214 billion, after tight regulations stifled the sector for decades.

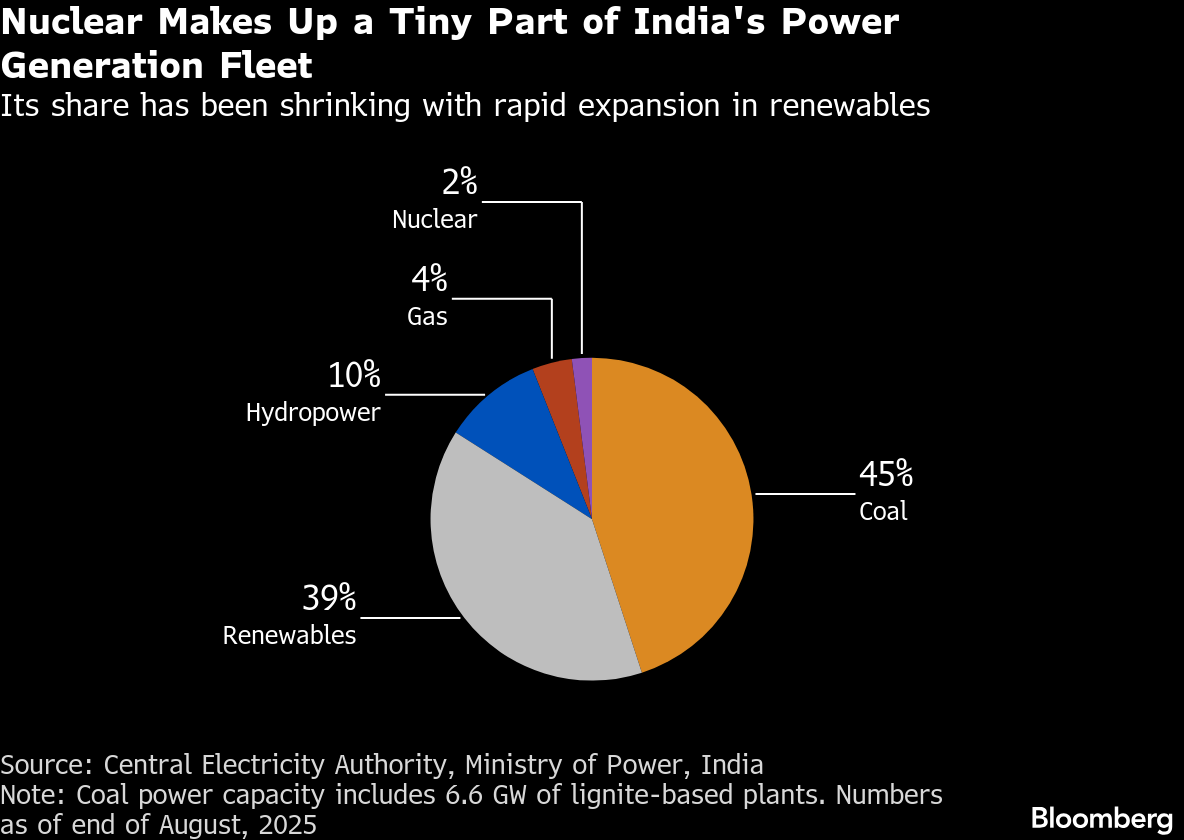

The bill comes at a time of renewed global interest in nuclear as a steady source of clean energy, and as part of India’s plan to expand its atomic fleet to to support economic growth and help decarbonize its coal-dependent economy. The proposed law abolishes the decades-old state monopoly in atomic power generation and makes sweeping changes to the country’s liability provisions that had spooked investors.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is counting on this law to revive the under-performing industry and boost capacity eleven-fold by 2047, a feat that will require nearly 19.3 trillion rupees ($214 billion) of investment, according to a government panel. The bill now needs to have the president’s assent to become a law.

“If we have to envisage a global role for ourselves, we have to follow global strategies,” nuclear energy minister Jitendra Singh said in parliament Wednesday, defending the choice to open up the sector to foreign investors.

Walchandnagar Industries Ltd., which supplies parts to nuclear power plants, rose nearly 8% in early Mumbai trade, reaching the highest intra-day level in about three months.

India’s push for nuclear echoes a global shift. Nations are shaking off their fears induced by the Fukushima meltdown in 2011 as they strive to meet growing demand from artificial intelligence systems and data centers. While Japan has begun to restart its reactors, China, South Korea and Bangladesh are among other nations building new ones.

Global nuclear power capacity could more than double to 860 gigawatts by 2050, pumping nearly $2.2 trillion into the value chain, Morgan Stanley Research wrote in a note in August. Its latest estimate of new global nuclear capacity by mid-century adds more than 50% to last year’s forecast, according to the note.

A large share of those additions could come from India should it reach its goal to have 100 gigawatts of nuclear power capacity by 2047, when it aims to attain energy self-reliance and graduate as a developed nation. Reaching those goals will involve a substantial rise in the country’s per capita electricity consumption, currently well below half of the world average.

India’s first nuclear test in 1974 led to a global freeze on atomic supplies to the country, reversed in 2008 by a deal with the US which restored India’s legal access to technology and fuel. While technically able to import what it needed to grow its nuclear fleet, after mounting public pressure the country introduced a controversial liability law in 2010 which has kept suppliers away until today.

The measure exposed suppliers to damage claims in the event of a nuclear incident and allowed litigation under various other laws. The risks it entailed stalled projects by Electricite de France, General Electric Co. and Westinghouse Electric that had signed up to build some of the world’s largest projects in India.

Currently, the Kudankulam plant near India’s southern tip operating Russian-designed 1-gigawatt reactors is the only one using foreign technology. The site has two reactors installed and four more are coming up.

The new bill spares suppliers entirely from nuclear liability and goes a long way to ease terms for the operators. It puts caps on liability according to the size of the reactors and allows the government to set up a liability fund to make good of any claims exceeding the limits.

“We are seeing profits being privatized, and risks being socialized,” Manoj Kumar Jha, who represents the Rashtriya Janata Dal opposition party, said in the upper house, echoing concerns that taxpayer money could be used to fill the fund. “We have to be careful of what we do; history doesn’t offer us a delete button.”

The bill also mentions it will prevail over any other law of the country in matters relating to nuclear, narrowing the prospects of litigation. Still, the government is not entirely giving up its control over the industry: Mining and processing of nuclear materials as well as management of spent fuel will continue to remain under state domain, as would the setting of nuclear power prices.

Any new infrastructure will have to meet the requirements of a price conscious Indian market. “The sector faces challenges including extremely high capital cost, long gestation periods and issues related to plant stabilization,” Ankit Jain, vice president and co-group head for corporate ratings at ICRA Ltd., said in an emailed statement. “Private firms lack operational track record in this domain, raising concerns over execution risks and tariff competitiveness.”

(Updates with shares in fifth paragraph and details of Russian-designed reactors in third paragraph after chart.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.