New York’s First Electric Skyscraper Promises Luxury With Lower Emissions

(Bloomberg) -- In a city that often feels stitched together by scaffolding, the development known as the Alloy Block — on a bustling street in downtown Brooklyn, across from the red-and-silver sign of the Brooklyn Academy of Music — long seemed like just another construction site.

But there’s something unique about the project’s first phase, a 44-story tower that opened this spring. Surrounded by buildings that rely heavily on gas and oil for energy, 505 State Street is New York’s first all-electric skyscraper.

Energy-efficient buildings like it will be crucial to the city’s push to cut its greenhouse gas emissions 80% over 2019 levels by 2050. Nationwide, the biggest single source of emissions is transportation, dominated by low-occupancy cars and trucks. But in New York, most people use mass transit instead of driving. That means buildings “are by far the largest source” of climate pollution in the city, said Christopher Halfnight, senior director of research and policy at the Urban Green Council, a nonprofit focused on energy efficiency in buildings. Gas- and oil-burning furnaces and water heaters are together responsible for 40% of NYC emissions, according to Halfnight.

To try to shrink that, the City Council in 2021 passed a law prohibiting new buildings from burning fuels that emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide. The rules took effect this year for most new structures up to seven stories high. But for towers, they won’t kick in until the middle of 2027. With 505 State, the developer-slash-architect Alloy Development is just getting a head start.

That wasn’t always the plan.

When Alloy first conceived of the project in 2019, “the assumption was the base building heat would be on gas, and maybe the cooktops would be gas,” AJ Pires, the company’s president, said during a walk through the site on a blustery day this past winter.

But two things happened. First, National Grid halted new gas connections in Brooklyn. It was part of a standoff between the utility and state regulators over a billion-dollar gas pipeline; the utility wanted it greenlit but regulators blocked a key permit, citing water-quality concerns.

Around the same time, the New York City Council passed Local Law 97, requiring a 40% reduction in GHG emissions from certain buildings by 2030, relative to 2005 emissions.

Though the law lacked clear guidance, the double whammy of gas connection woes and pending regulation led Pires and his colleagues to bet the city would over time incentivize electrification, or “penalize anything that was using a carbon-based fuel,” he said. “And that ended up being true.” So they decided to go electric.

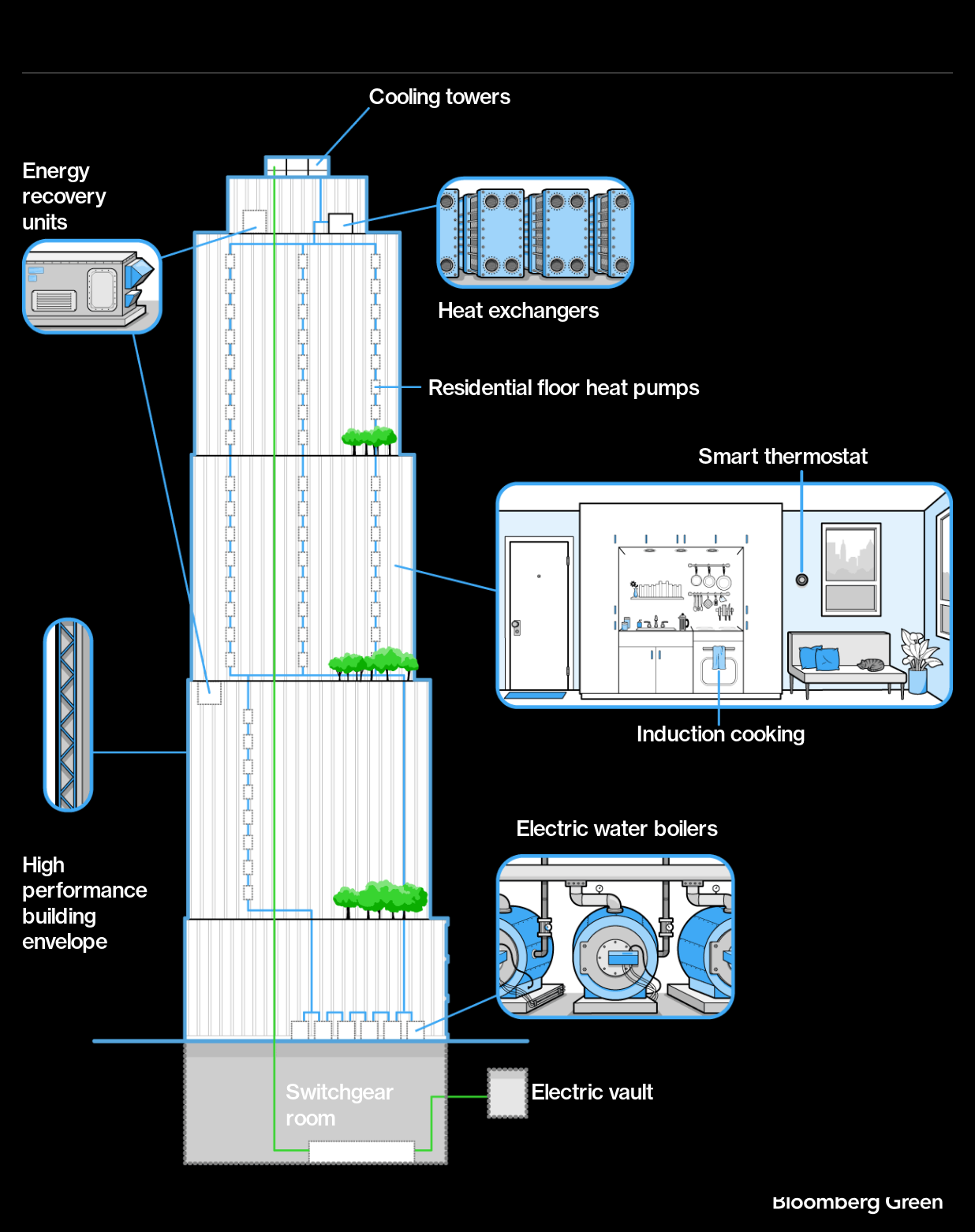

When team members asked what the complex would look like absent gas, the answers were fairly straightforward. “Instead of a gas boiler, an electric boiler; instead of a gas cooktop, it was an induction cooktop. And literally that was it,” said Pires, noting that they had to revise the design of the electrical room to allow for higher amperage, since more incoming electricity would be needed for a larger electrical load.

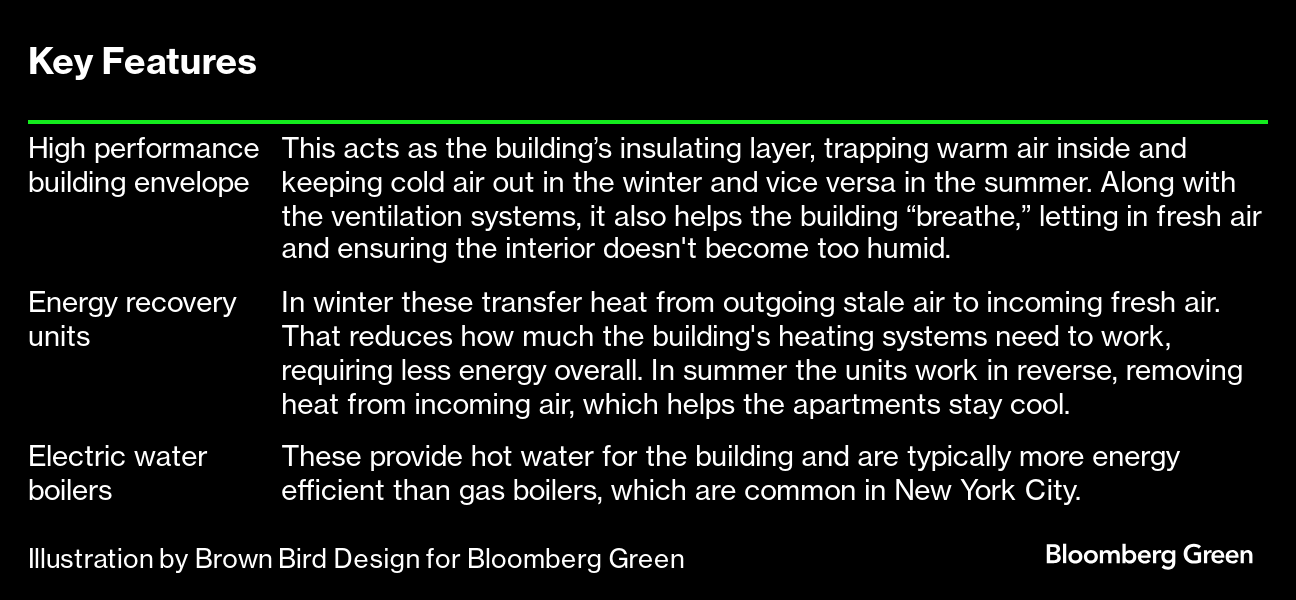

Luckily, Alloy already had experience designing buildings that conserve energy, like One John Street, a mixed-use residential and commercial development in Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighborhood that won an American Institute of Architects-New York award for its high level of sustainability. And they’d already designed the five structures that make up the Alloy Block with tight building envelopes to reduce the energy needed for heating and cooling.

The bigger difficulty was getting the school building authorities on board. The project site includes the current home of Khalil Gibran International Academy, the first English-Arabic public school in the US. Its building is an amalgamation of several structures built between 1873 and 1889. “But they were obviously inefficient for today’s high schools,” said Jennifer Maldonado, chief executive officer of the Educational Construction Fund. The ECF builds public schools across New York state through public-private partnerships.

Alloy Development’s plans called for refurbishing the old school for use by the community and apartment residents, and for moving Khalil Gibran into a new building at the center of the complex, along with a new 500-seat elementary school (P.S. 456). That building would meet the standards of Passive House — a design approach in which structures are so tightly constructed that they require very little energy to maintain comfortable interior temperatures.

“We declared that it would be a Passive House school building, to sort of set up a pilot for the School Construction Authority to test out new ways of building schools,” said Pires. Whereas the Educational Construction Fund oversees the school’s construction, once it’s finished the School Construction Authority will take possession of the property and be responsible for maintenance and upkeep. Across the city, the SCA maintains more than 1,400 buildings serving 1.1 million students. It is one of the city’s largest builders, and as such is a key part of helping the city lower building emissions. But because it serves a specific population — youth — it also has specific and strict requirements.

“There’s little things, like where banisters are put, where entryways are located, where security cameras are placed,” said Maldonado, noting that schools built for younger kids have railings and toilet bowls placed at lower heights than schools constructed for teens. Because this is a busy part of Brooklyn, windows were required to be triple-paned to isolate outside noises.

The main challenge was meshing Passive House requirements around heating and cooling with the SCA’s rules for ventilation, cooling and air systems. Engineers, architects and construction managers collaborated to get them in sync, Maldonado said: “In terms of building new buildings, this could potentially be a model moving forward.”

Like 505 State Street, the new school building will mark a first — the first Passive House public school in the city. It will open to students in September. Tenants of the residential tower, meanwhile, began moving in on April 5. Market rent ranges from $3,475 for a studio to $11,200 for a three-bedroom, although 45 of the 440 units were set aside as affordable housing.

The model unit that Pires showed off looked like any apartment in a new luxury building, with sleek, modernist fixtures and tall windows of triple-pane glass, designed to both quiet the cityscape outdoors and maintain comfortable indoor temperatures. The glass cooktop is induction, which some chefs say is superior to gas for its responsiveness. Each unit is equipped with an Ecobee smart thermostat that not only lets residents schedule when the heating and cooling turn on and off, but can also sense when the apartment is unoccupied and revert to a lower energy setting.

But much of what makes the building tick is outside of the tenant’s purview.

Heating and cooling operate on what’s known as a water-source heat-pump system. “That means there’s a loop of cold water and a loop of hot water that go to the units that are in the apartments, that then blow air over the loops, and heat and cool the spaces,” said Pires. The water loops recover much of the energy used for warming and chilling, reducing how much the boiler has to work and thereby maximizing efficiency

When Andrew Graham, Alloy Development’s asset manager, led us down to the basement, it was startlingly clean, and missing the tang in the air that usually accompanies gas boilers. 505 State Street has an electric resistance boiler instead. Pires noted that the building does have one exception to its all-electric credentials — a backup gas generator in case of emergency, which according to Pires was a building code requirement.

The backup generator will kick in if the building loses power, to ensure that the elevator and the lights in the fire egresses work. “It’s not part of the daily operations of the building. It’s not being used. But it does provide life safety services if there’s a blackout,” said Pires.

One common concern about electrified buildings is cost, both for developers and tenants. Halfnight pointed to recent research suggesting that for developers, all-electric new construction in New York City “is basically cost-neutral compared to a non-all-electric building.”

For renters it’s more complex. Many New York apartment buildings control the heating and cooling centrally and fold the costs into rents rather than give tenants a discrete bill. This isn’t without downsides — unable to turn down the heat, New Yorkers often prop open windows in winter — but it also means costs are consistent. Tenants in the Alloy Block will be able to control their own heat, but they’ll also have to pay for it themselves.

Pires acknowledged that Alloy — as the landlord — won’t really know the energy costs, relative to conventional heating and cooling, until the building is fully operational. “I’m curious to see what my electricity bill is gonna be like when we turn it on and use it,” he said.

As more new buildings in the city go electric, “there’s work to be done to make sure that that transition happens in a way that is equitable and ensures that residents are not paying undue portions of utility bills,” said Halfnight of the Urban Green Council.

Rapid changes in technology may allow more dramatic efficiency gains in the later phases of the project. While 505 State Street relies on an electric resistance boiler, the second residential tower will feature newer tech. “We are designing the second building now, and there’s air-source heat pumps that can produce enough hot water that weren’t available five years ago, when we were designing 505 State Street,” said Pires. Heat pumps are more energy efficient than electric resistance boilers.

In its enthusiasm for going electric, Alloy Development stands in contrast to others in the real estate and construction sectors who’ve resisted New York’s green building push. In 2022 two Queens co-ops and an LLC that owns a building in Manhattan filed suit in New York Supreme Court to overturn Local Law 97. That case was dismissed in 2024. Meanwhile, the state’s All-Electric Building Act — which mirrors the New York City law but with a slightly longer timeline for adoption — is being challenged in a federal district court. Fossil fuel companies, trade associations and unions whose members rely on the availability of gas appliances and systems for their livelihoods filed suit in October 2023.

From Pires’s perspective, it’s where the tide is heading and he and his colleagues just got there a little early. Of the engineers who worked on 505 State Street, he said, “if you ask them now what they’re doing on any multifamily building, they’re all-electric — all of them. It’s super great to be able to use the project to promote that type of a future.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More utilities news

Equinor takes FID on UK’s first carbon capture projects at Teesside

BMW, Mercedes Add New Executives as Carmakers Tackle Crisis

Thames Water CEO Steers Away From Break Up After Covalis Bid

Germany Expecting Tight Power Conditions as Wind Output Falls

Nuclear Power Not Cost-Effective in Australia, Science Body Says

Vancouver Mayor Proposes Using Bitcoin in City Finances

Thames Water Gets £5 Billion Takeover Bid From Covalis

Lithium Powerhouse Chile Eyes New Lithium Extraction Methods

Aramco, Linde and SLB to build one of the largest CCS hubs globally