Missing billions threaten to break Britain’s energy market

(Bloomberg) --

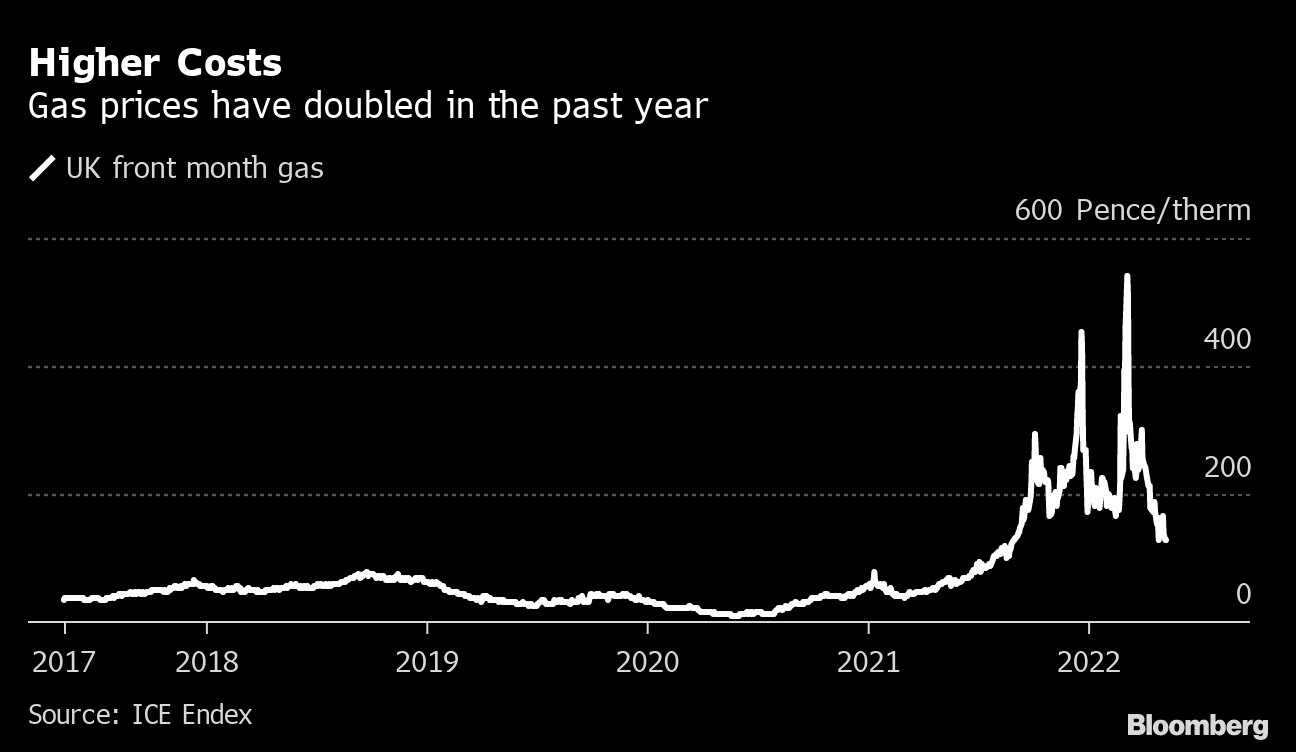

The war in Ukraine has exposed the vulnerability of the energy industry across Europe, but the UK market is looking increasingly perilous for suppliers and consumers for reasons closer to home.

Utilities are now on the hook for billions of pounds of unpaid bills after the prices of gas and electricity soared as households already struggling with the cost of living go into debt. It’s also becoming clear that what people pay is unlikely to fall even if wholesale prices do because of the costs associated with rescuing the customers of more than two dozen smaller suppliers that failed when prices surged last year.

It’s too early to put an overall figure on what customers owe, but the picture is bleak based on recent estimates. Companies such as Iberdrola SA’s Scottish Power are warning the market is no longer sustainable.

Money owed by EON SE’s customers is expected to increase by 50% to 2.4 billion pounds ($3 billion) by the end of the year, Michael Lewis, who runs the German company’s UK business, told a parliamentary committee last month. Centrica Plc, Britain’s biggest supplier, meanwhile says 10% of its 7.2 million customers are already behind with payments.

The issue, companies and energy analysts say, is that the structure of the UK’s energy market means it’s trapped in a vicious cycle just as the Bank of England warns of recession and double-digit inflation. Suppliers are charging more while households have less ability to pay because of a squeeze on incomes driven by food, a payroll tax increase and now rising interest rates.

“It is slowly dawning that the cost of living crisis is not going away,” said Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford University and a former energy policy adviser to the government. “And that of all the bills which citizens face, the energy bills are the ones that really stick out.”

The UK’s cap on energy prices, originally designed to protect consumers from sharp increases, surged 54% to a record on April 1, affecting 22 million people. It’s predicted to jump again at the next adjustment in October. That could put 40% of the population in fuel poverty and likely lead to more unpaid bills, according to supply companies.

While some politicians are calling for a tax on companies to subsidize consumers, the industry says it no longer has the financial cushion it once had. Profit margins for selling power and natural gas to households have been negative on average since 2019 as competition between suppliers and the price cap kept a lid on how much they could charge, according to a report by Oxera Consulting LLP.

Scottish Power recorded a loss of about 250 million pounds selling energy to households last year. EDF Energy said it also lost money. Centrica’s British Gas showed a more mixed picture, losing out from selling electricity but making 222 million pounds supplying gas.

“The problem is going to get more severe, and for suppliers it’s not a high-margin business anymore so a rise in bad debt could be quite detrimental,” said Josh Buckland, a partner at Flint Global and a former government energy adviser. “There is no immediate quick fix.”

The Bank of England is assuming energy prices will stay high after what it called the biggest shock since the 1970s crisis. That will continue to drive inflation, curb economic growth and hit households for years.

The price cap protects households not on a fixed-term tariff from being put on the most expensive deal. The level is adjusted twice yearly based on prices in the previous six months. It stops companies having to absorb higher wholesale costs indefinitely, but defers how quickly they can pass on lower prices — essentially just postponing the day of reckoning.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak laid out a 9 billion-pound package that includes a 200-pound upfront discount on energy from October for households. While he’s said it’s possible the government could increase aid before next winter, it’s unlikely to expand measures before then. Oxford’s Helm referred to the Chancellor’s plan, unveiled in February, as “moving the deckchairs on the Titanic.”

The scale of the problem has gone beyond what the industry can deal with, Keith Anderson, CEO of Scottish Power told BBC radio on May 9. He called for a “massive, significant shift in government policy.”

“We will end up seeing people self-disconnecting and a massive increase in the level of debt, and the cost of the debt will end up going onto future bills,” he said. “You will see a lot of strain and stress put on the remaining providers in the market because, as I say, how long can companies keep making a loss year after year?”

Other European governments are keeping a much tighter grip on rising prices. Electricite de France SA, for example, is majority government-owned and could have some of its assets nationalized to help pay down debts from measures like a price cap introduced to help households.

In the UK, the government has intervened to rescue customers of companies that went out of business because of the surge in prices last year. Most of those firms, some with just a few hundred customers, were the result of a deregulation of the market that allowed just about anyone to set up an energy supply company. Bill payers ultimately will be saddled with the burden, according to regulator Ofgem.

Bulb Energy Ltd., the biggest supplier to fail, is set to cost 2.2 billion pounds by the end of 2023, according to forecasts by the UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility. Ofgem estimates the other 25 company failures will cost consumers about 2.4 billion pounds, which will be claimed back through bills.

There’s also another twist. Because households are likely to seek a cheaper deal when prices start to drop below the price cap, Ofgem will limit the financial impact on companies that have taken on the customers of failed suppliers. That involves introducing a charge payable by firms gaining the clients who switch. And ongoing costs associated with Britain’s net-zero target for reducing emissions are also in the mix: the build out of renewable energy is passed on to consumers.

“You have to assume elevated prices for a year or two years,” said Buckland. “We can’t have the companies in a holding pattern, disengaged customers and a push to decarbonize homes. It’s not credible.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More utilities news

BMW, Mercedes Add New Executives as Carmakers Tackle Crisis

Thames Water CEO Steers Away From Break Up After Covalis Bid

Germany Expecting Tight Power Conditions as Wind Output Falls

Nuclear Power Not Cost-Effective in Australia, Science Body Says

Vancouver Mayor Proposes Using Bitcoin in City Finances

Thames Water Gets £5 Billion Takeover Bid From Covalis

Lithium Powerhouse Chile Eyes New Lithium Extraction Methods

Aramco, Linde and SLB to build one of the largest CCS hubs globally

UK Nuclear Plants to Stay Online Longer in Clean-Power Boost