‘Stunning’ Solar Activity Is a Warning to Grid Operators

(Bloomberg) --

Late last week, the Sun blasted millions of tons of super-heated gas off its surface toward Earth and everyone on it.

Then it happened again, and again, and, well, you get the idea. The brilliant auroral displays captured around the world this past weekend will lead to a better understanding of what the star can do. You can almost hear those research papers being written, and they could help us understand how to protect crucial infrastructure.

By Friday, the Sun had sent five of what are known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) hurtling 93 million miles toward Earth. Another string of CMEs have come flying off the Sun’s surface, putting this event in rare territory.

“The thing that is stunning to me is how rapidly it put out so many Earth-directed CMEs,” Michael Wiltberger, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who studies CMEs. “That is something I have never seen before.”

How a hyperactive sun affects the climate won’t necessarily be tops on their list. The Sun goes through cycles where it produces a lot of sunspots and then hardly any, at roughly 11-year intervals. So-called solar cycles can have an influence on the climate albeit a small one compared to human emissions and other natural shifts on Earth such as El Niño.

The myth that the Sun will save the Earth from global warming has been a popular meme among climate deniers. The reasoning was that there was a time in history when the Sun didn’t produce a lot of spots called the Maunder Minimum, which happened during a period when temperatures across Europe dropped so much so that the time period is known as the Little Ice Age. Yet while there was overlap, the Little Ice Age began before and lasted longer than the Maunder Minimum, which only ran from 1645 to 1715.

The world has been in a quiet period for sunspots over the past few decades, yet global temperatures have surged to record highs. The Sun is currently producing more spots than it did in at least the last two cycles, and 2023 was the hottest year on record. The first few months of 2024 have been even hotter (though La Niña may emerge and cool things a bit).

While it’s safe to say the Sun won’t suddenly reverse the trend of global warming or speed it up, this weekend’s events will spur a flurry of other research that could be particularly helpful for operating the grid and surging renewable infrastructure.

Those coronal mass ejections are streams of charged particles that interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and can impact all sorts of modern technologies. The first indication humans had that the forces that caused the aurora had real consequences came in 1859 when a massive geomagnetic storm hit the planet. Telegraph offices burst into flames as electric current coursed through wires, pipelines were energized and the aurora may have been seen as far south as Hawaii.

This weekend’s surge was nowhere near the intensity of that geomagnetic storm, which is known as the Carrington Event. That’s a good thing. Estimates early in this century found that a storm of that magnitude could cost $1 trillion to $2 trillion and take four to 10 years to recover.

The world has been getting ready. The US and UK have built space weather centers to issue forecasts and monitor the Sun, and other countries have followed suit.

Yet while the Sun shines brightly in the sky, we still have a lot to learn. The giant sunspot cluster that caused this weekend’s aurora and stressed out grid operators will roll around the back of the star. No one will know what it is doing until it comes back — if it comes back — several weeks from now.

Researchers will continue gathering data on the rare event, and reams of research will land on journal reviewers’ desks in the coming month just as surely as birds will fly south for the winter.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

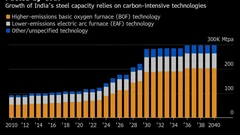

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture

Blackstone’s Data-Center Ambitions School a City on AI Power Strains

Chevron Is Cutting Low-Carbon Spending by 25% Amid Belt Tightening

Free Green Power in Sweden Is Crippling Its Wind Industry