Battle to Save Coal Plants Stalls Offshore Wind in Brazil

(Bloomberg) -- A battle in Brazil’s Congress to save coal plants is holding up a much-vaunted offshore wind industry in Latin America’s largest economy.

A bill to regulate the business is currently stalled after a group of lawmakers introduced a series of amendments, including one to extend coal-fired thermal plants through 2050. An opposing group of environmentally minded lawmakers are up in arms over the maneuver, and even state-controlled oil producer Petroleo Brasileiro SA has criticized the move.

At stake is how fast Brazil can start offshore wind parks that cost billions of dollars and can take nearly a decade to complete. Brazil plans to use this clean energy to diversify its energy mix and attract billions in foreign investments. President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has pitched the green transition and decarbonization as one of his administration’s biggest priorities, and he has made climate change a major theme of Brazil’s presidency of the Group of 20 nations.

“Brazil doesn’t have time to waste, and it’s particularly worrying that the law is being held up because of the inclusion of measures meant to prolong obsolete and dirty coal powered generation,” said Ben Backwell, the chief executive officer of the Global Wind Energy Council, who visited Brasilia in March to try and get the law moving. “If Brazil wants to be the green economic powerhouse of the future, it needs to create the conditions now as these are big, long term investments.”

The amendments in the wind bill, which also include compulsory contracting of gas-fired power plants, are expected to cost a total of $7.8 billion, according to Abrace, an association of large energy consumers. They will also increase the cost of energy by 11%, said Victor Hugo Iocca, the association’s director of electric energy.

Coal-fired thermoelectric plants in Brazil are usually turned on when energy produced by cheaper and cleaner hydroelectric plants isn’t enough to satisfy demand. More than 80% of Brazil’s electricity comes from renewable sources such as hydropower, wind, solar and biomass.

The government isn’t in a hurry to get the law passed because it wants lawmakers to reach an agreement on the polemic measures, according to people with knowledge of the discussions. The bill needs to become law before Brazil can start holding licensing rounds for large-scale wind projects. Developers are hoping to get the first offshore wind farms running by around 2030.

“We are waiting on the starting pistol,” said Jonathan Cole, the chief executive officer of offshore wind developer Corio Generation Ltd., which has set up an office in Rio de Janeiro in anticipation of licensing rounds. “There are a lot of big players sitting with projects that they are very excited and optimistic about.”

The bill’s rapporteur in the lower house, José Vitor Aguiar, said he was “very optimistic” that it will get passed even with the costly amendments, because lawmakers want to see the investments go forward, and to see Brazil become a major producer of green hydrogen. If projects don’t get off the ground, other countries in Latin America could move faster and take control of the market before turbines start spinning off Brazil’s coastline.

For hydrogen to be considered green it needs to be made with renewable power, and Brazil’s strong winds and blazing sun make it one of the most competitive places for clean energy.

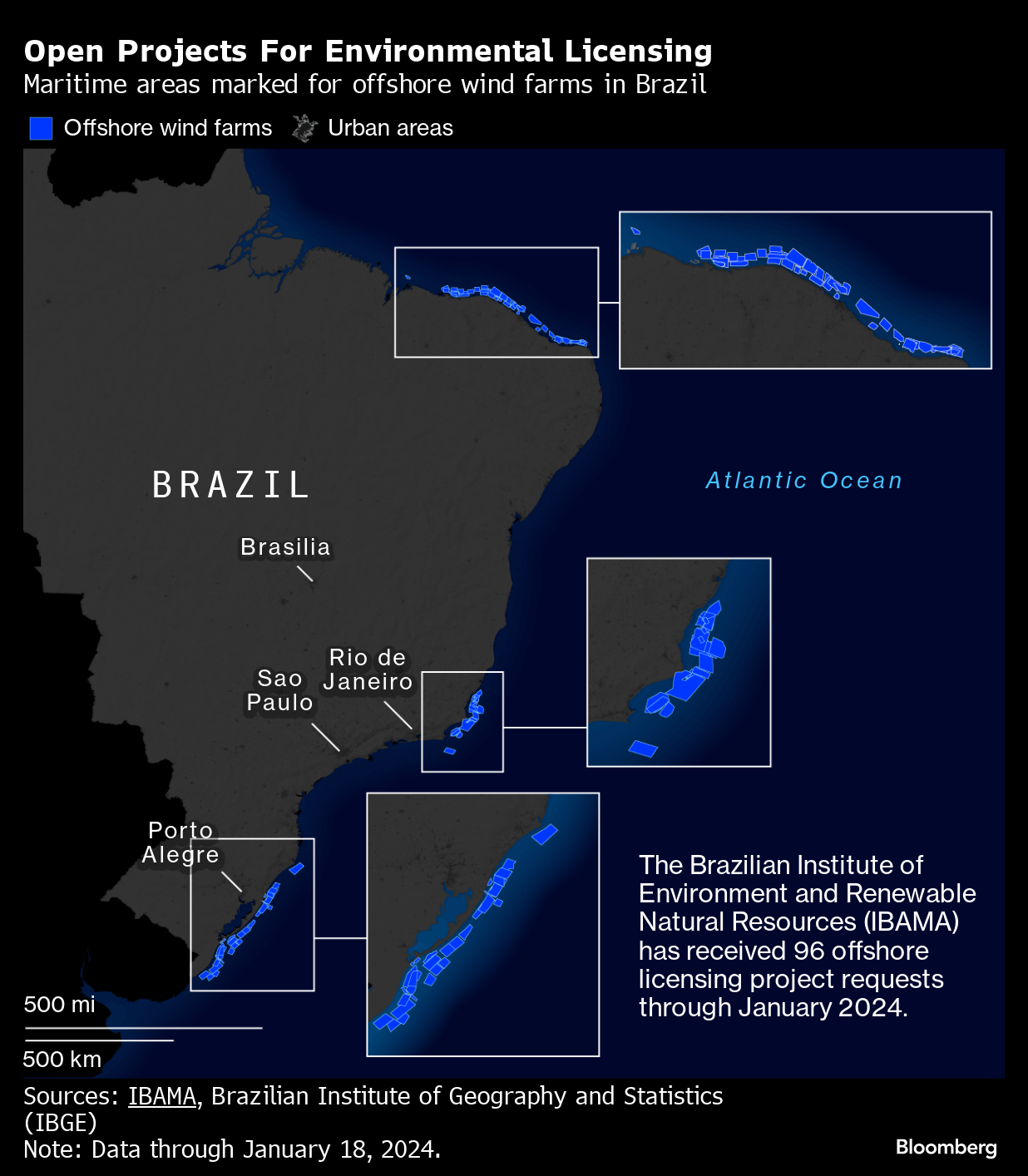

Brazil — with one of the longest coastlines in the world — has 190 gigawatts of projects waiting for permits, and a total offshore potential of 700 gigawatts, according to an energy research agency known as EPE. By comparison, The UK and China, two of the world’s largest producers of offshore wind, have a estimated potential of 50 gigawatts and 1,000 gigawatts, respectively.

Offshore wind is a big part of the government’s plan to turn Brazil into an industrial powerhouse with new manufacturing hubs up and down the coast. The equivalent amount of investment in offshore wind creates twice as much economic growth compared to onshore wind, said Elbia Gannoum, the head of the Brazilian Wind Energy Association, an industry group.

Offshore wind can also help Brazil reduce reliance on its legacy fleet of hydroelectric dams.

“Hydroelectric plants leave us dependent on the rain cycle, which has been impacted by climate change and increases the risk to the system’s stability,” said Vinicius Nunes, BloombergNEF analyst in Sao Paulo.

While Brazil is blessed with strong winds and a large market for electricity, there are concerns that the industry could see the same kinds of difficulties seen in the US. Rising inflation, supply-chain constraints, and low electricity prices have doomed some offshore parks in off the East Coast.

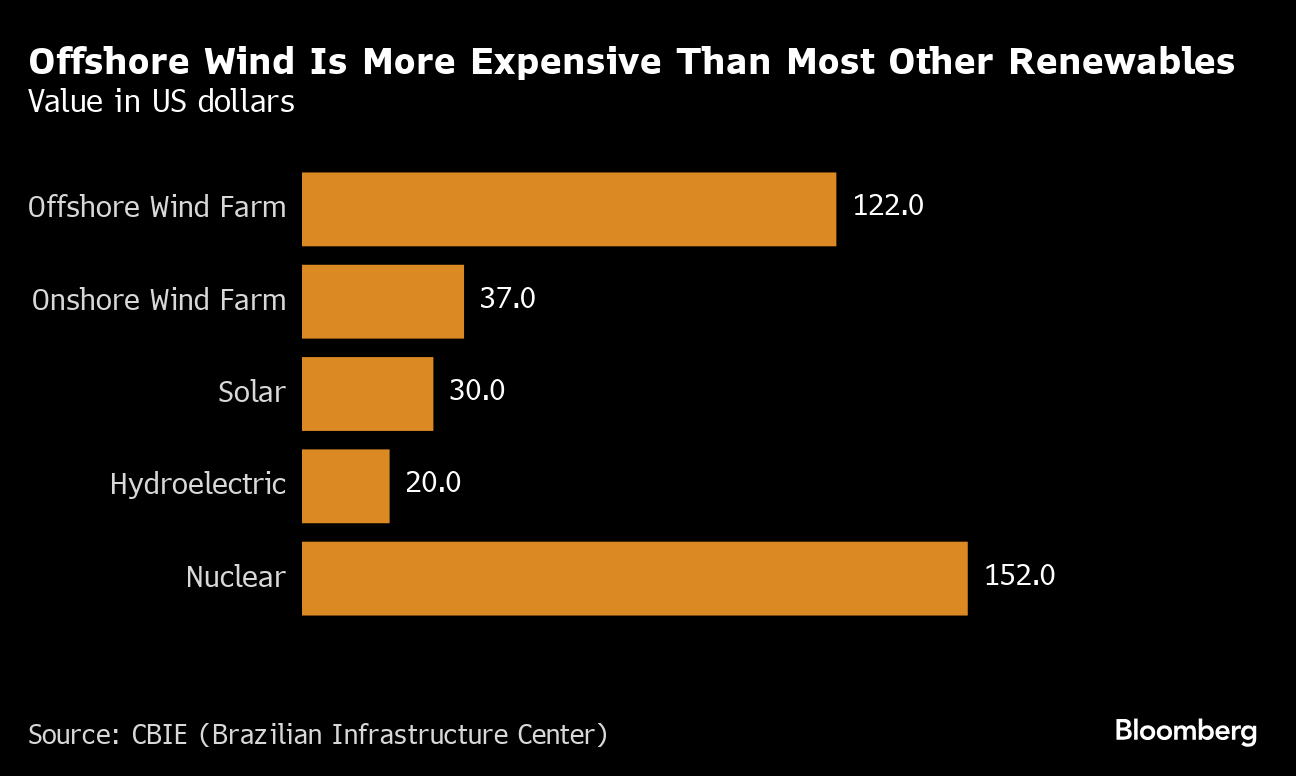

The cost of offshore wind production in Brazil is still high, second only to nuclear energy. Considering the energy abundance promoted by hydroelectric plants, diversifying production with a more expensive matrix can be challenging for the country and its companies.

(Adds comment from Global Wind Energy Council in 4th paragraph)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals