Barclays Sees Real Greenwashing Risk in ESG Debt-Swap Market

(Bloomberg) -- As cash-strapped emerging-market countries explore the option of debt relief in exchange for commitments to preserve nature, researchers at Barclays Plc say that some of the labeling smacks of greenwashing.

“At first glance, this is a win-win solution — heavily indebted countries can reduce debt and interest burdens, while resources can be directed towards conservation projects that support overarching nature-related goals,” Barclays analysts including Charlotte Edwards and Maggie O’Neal said in a client note on Monday. “However, tackling debt burdens and climate goals together is not always ideal.”

There’s evidence that the amount of money that goes toward the nature conservation goal attached to such deals is only a small fraction of the transaction size, which means the products are “misleading” in their packaging, Edwards and O’Neal said.

With the market for debt-for-nature-swaps potentially set to exceed $800 billion in global public and private deals, the Barclays analysts say it’s time to apply more scrutiny to such deals.

After lying dormant for more than two decades, the debt-for-nature-swaps market has enjoyed a revival as the finance industry explores all forms of environmental, social and governance strategies to boost ESG metrics. Such programs also offer debt relief to countries that are both poor and disproportionately exposed to the ravages of climate change.

Belize recently struck a deal to restructure $553 million of debt in exchange for pledges on marine conservation. Such an arrangement, led by private investors without the involvement of the group of government creditors known as the Paris Club, is likely to become more common given “heavy debt burdens and the shared global interest in sustainability,” Edwards and O’Neal said.

However, “allocations to environmental projects can fall well short of amounts saved in debt repayments,” they said. “There is also a real risk of greenwashing, especially if funds to repurchase debt are supplied by a third-party funding itself via ESG-labeled bonds.”

Blue Bonds

“We are concerned about the use of the term ‘blue bonds’ in aspects of debt for nature transactions,” Edwards said in an interview. “Blue bonds are a type of green bond, and the point of a green bond is that 100% of the proceeds that are raised are spent on environmental projects.”

In the case of Belize, just $84 million of the $553 million deal actually went toward marine conservation, Barclays estimates. A further $86 million is allocated to intermediaries and service providers such as re-insurers, advisers and credit providers, Bloomberg News has reported. That’s on top of the $10 million originally disclosed by Belize, to help cover the closing cost for the transaction.

“The term ‘blue bond’ is maybe not always being used in line with what many people in the market think of as a blue bond, where 100% of proceeds go towards blue products,” Edwards said.

That raises questions around the impact of these deals, “particularly when each additional party entering the transaction takes a cut from the proceeds,” Edwards and O’Neal said in the client note.

“This ties into a concern we have around transactions involving third-party entities issuing bonds labeled as blue, where proceeds are used as a loan to a debtor government to repurchase debt,” they said.

Environmental and debt justice advocates have also warned that such financing arrangements raise numerous concerns. Last month, a group of 31 nonprofits criticized debt-for-nature swaps for locking public funds into conservation organizations, potentially at the cost of other societal needs including health care and education. There’s also a worry that the swaps may jeopardize wider and lasting reforms to debt management. “The risks and pitfalls of turning to financial markets to fund marine conservation are being ignored,” the group said.

Issuers of green bonds, of which so-called blue bonds are a subset, are supposed to direct all of the proceeds into environmental projects. “However, in examples we have seen, the proceeds of these blue bonds are financing the purchase of bonds, of which only a relatively small subset will go into nature projects.”

The upshot is that the label is “misleading, possibly exacerbating concerns over the quality of the ESG-labeled market,” Edwards and O’Neal said.

--With assistance from and .

(Adds additional comment from Barclays analyst from interview)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

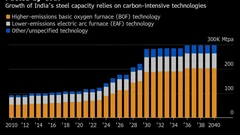

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals