Chinese Monks Get Electricity for the First Time Thanks to Solar

(Bloomberg) -- It takes three hours of hiking along rock stairs and muddy walkways to reach Boluo Temple in the Chinese city of Dali, where by some accounts monks have lived since as early as the Tang Dynasty. For more than a thousand years, devout inhabitants have practiced their beliefs from the prayer hall near the mountain peak, collected water from snow melts and sourced nearly all of their heating needs by burning fallen branches. At least until recently.

In just the past few years, the centuries-old temple for the first time gained access to electricity — not from the country’s grid, but thanks to solar panels installed in its backyard. “We never bought electric appliances before, and cooked and boiled water using firewood,” said Ming Jing, a 32-year-old junior monk at the temple. “This is a great improvement of convenience for our lives here.”

China has spent billions of dollars on connecting its entire population — including the most rural villages — to its mega grid system. However, in far-flung locations where grid access isn’t possible, solar panels have become the only choice for electricity.

With 10 panels connected to a battery box the size of a medium checked-luggage bag, the system at Boluo Temple provides power for the lives of Ming Jing and the head monk, as well as a ginger cat named Flower. They now own a few small electronic devices, namely a water boiler, induction cooker and a space heater.

During the winter, temperatures can plunge below 0C in the mountain monastery, located about 2,700 meters above sea level, making nights especially tough to bear. “Without a heating pad, lying into the blanket was like lying on ice,” Ming Jing said. Now, solar panels provide enough electricity to keep the electric blanket running for six to seven hours per night — if the preceding day was particularly sunny.

Since the start of this century, the Chinese government has made it a priority to provide electricity to its 1.4 billion citizens through national development plans, including paying the partial cost of power line construction projects that are not commercially profitable for grid builders. For the 1.2 million people that were still living off-grid in the early 2010s, China invested 4 billion yuan ($591 million) between 2013 and 2015 to build over 670 standalone solar power plants and 350,000 home photovoltaic systems, according to the National Energy Administration.

Among other things, solar is being used as part of a poverty-alleviation effort in China, with over 26 gigawatts built in poor areas across the country as of 2019. As part of the plan, the government has sponsored rooftop or small-scale ground installations in poor areas so that villagers can have better energy access and cheaper electricity, while reducing the use of polluting fuels like wood for daily activities such as cooking and heating. Villagers can also profit by selling electricity generated from rooftop solar panels back to grid companies.

A study on the solar poverty-alleviation program, published in 2020, found the installations have raised disposal income per capita for beneficiaries by about 7% to 8%. Residents of the targeted areas are benefiting from not just selling electricity to the grid, but also job opportunities brought by the projects and more stable power supply overall, according to one of the report’s authors, Yueming ‘Lucy’ Qiu, an associate professor in the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. She noted that program has downsides, too: Many of the solar systems are not properly maintained, and panels sometimes take land space that may have been used for other purposes, such as agriculture. “The opportunity cost needs to be considered,” she said.

Boluo Temple spent more than 30,000 yuan ($4,430) on its solar system. Ming Jing and his master took a loan from a larger nearby temple and have yet to pay it off; they have limited means for raising funds. The temple put out a poster asking for donations for the solar system; as they’re located along a popular hiking trail, the monks also raised money by selling vegetarian meals to passing tourists at 20 yuan each.

Still, the temple’s power supply is far from enough to support a modern lifestyle, and there can be little to no electricity generated on days without enough sunlight. Ming Jing said they won’t add more panels, though, as the lack of power and internet also helps with his practice and self-exploration.

“We don’t have any room to install more and, in fact, this is already sufficient for us,” he said. “We didn’t come here for a convenient life.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

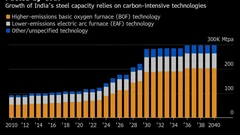

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture