Offshore Wind Sends Some North Sea Birds Fleeing, Study Finds

(Bloomberg) -- Red-throated loons — a type of water bird that ancient Gaels relied on to predict the weather — are so avoidant of offshore wind turbines in the North Sea that their numbers declined significantly in the immediate vicinity, a new study finds, adding to concerns about balancing the world’s push for renewable energy with the need to protect biodiversity.

The study, published Thursday in the peer-reviewed journal , investigated how the abundance of the birds had changed since 14 offshore wind farms were constructed in the southeastern waters of the North Sea. Using data collected from ships, aircraft and digital aerial surveys each year during March and April, the researchers recorded a downward pattern from 2010 to 2017.

The study shows the overall population of almost 35,000 loons, primarily red-throated loons, in the observed sites fell by nearly 30% after the wind farms were built. The loons shied away from all 14 wind farms, with their numbers declining by as much as 94% within a 1-kilometer zone.

“This worries us substantially,” said Stefan Garthe, a co-author of the paper and a marine ecology professor at Kiel University in Germany. “While we acknowledge the urgent need for renewable energy, we face the problem that wind farms hardly provide any benefit for seabirds.”

The installation of wind turbines offshore isn’t always bad news for marine conservation. For instance, mollusks and small fish have been shown to turn turbines into artificial reefs. But seabirds seem to face a high risk of fatal collisions and habitat loss. Red-throated loons are unusually avoidant of human activity, but other species including white-tailed eagles and skuas are exposed to adverse effects of offshore wind development, a separate 2013 study showed.

Garthe said his team was “surprised” that the decline even occurred at distances larger than 5 kilometers away from the wind farms. In fact, the disruption was so far-reaching that the loons’ population more than halved within a 10-kilometer zone, according to the study.

Fish-eating, migratory birds that are also known as divers, red-throated loons are not endangered but are protected under a UN-backed international treaty. In recent years, their numbers have been decreasing due to intensified ship traffic, oil spills and, increasingly, a changing climate that affects the distribution of fish stocks. The researchers warn that the installation of offshore wind turbines will likely pose another blow as birds are now forced to live in a smaller feeding ground.

The migratory birds are a food source for indigenous people in Canada and traditionally played a role in weather forecasts in Scotland. The behavior of the red-throated loon, according to Gaelic tradition, might be used to predict rain or bad weather, earning the bird the nickname “rain goose.”

The North Sea is in the center of a dilemma facing global policymakers. It is home to a wide array of marine life, but it is also key to Europe achieving its goal of ditching planet-warming fossil fuels. Last year, Germany, Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands pledged to install a total of 150 gigawatts of wind energy in the North Sea by 2050.

To keep the world’s temperature rise below 1.5C, almost 90% of the world’s electricity will have to come from solar panels, wind turbines and other renewable energy sources, up from about 30% now, the International Energy Agency estimates. But adding more renewable energy projects can also come with an ecological cost. Hydroelectric dams disrupt migration routes for fish. Concentrating solar thermal plants, a form of solar energy that harnesses heat from sunlight to produce electricity, risk incinerating insects. Wind turbines pose a threat to whales, including critically endangered right whales, although the extent to which they’re implicated in recent whale deaths along the US East Coast is unclear. (Off the coast of Massachusetts, wind developers are testing an artificial intelligence tool developed to detect whales and avoid potential collisions.)

“Although renewable energies will be needed to provide a large share of our energy demands in the future, it is necessary to minimize the costs in terms of less-adaptable species, to avoid amplifying the biodiversity crisis,” the researchers noted in their paper.

The authors call for the creation of more marine protected areas to safeguard vulnerable species such as red-throated loons. “This would provide a kind of compromise between renewable energy installation and prevention of biodiversity loss,” Garthe said.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

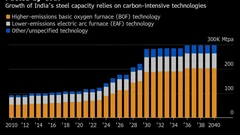

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals