Desperate Europeans Return to the World’s Oldest Fuel for Warmth

(Bloomberg) -- Not far from Berlin’s Nazi-era Tempelhof airport, Peter Engelke is putting up a new security gate at his warehouse because of concerns about desperate people pilfering his stock. The precious asset at risk is firewood.

Engelke’s actions reflect growing anxiety across Europe as the continent braces for energy shortfalls, and possibly blackouts, this winter. The apparent sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipeline is the latest sign of the region’s critical position as Russia slashes supplies in the standoff over the war in Ukraine.

At a summit in Prague on Friday, European Union leaders fell short of agreeing on a price cap for gas amid concerns that any such move could threaten supplies to the region. As much as 70% of European heating comes from natural gas and electricity, and with Russian deliveries drastically reduced, wood — already used by some 40 million people for heating — has become a sought-after commodity.

Prices for wood pellets have nearly doubled to 600 euros a ton in France, and there are signs of panic buying of the world’s most basic fuel. Hungary even went so far as to ban exports of pellets, and Romania capped firewood prices for six months. Meanwhile, wood stoves can now take months to deliver.

Aside from concerns about shortages, the energy crisis is intensifying a surge in living expenses, with euro-zone inflation hitting double digits for the first time ever in September. Strapped households across the region are increasingly faced with choosing between heating and other essentials.

“It’s back to the old days when people wouldn’t have the whole house heated,” said Nic Snell, managing director at British wholesale firewood retailer Certainly Wood. “They’d sit around the fire and use the heat from the stove or open fire and go off to bed. There will be a lot more of that this winter.”

The trend has meant a boom in demand for Gabriel Kakelugnar AB, a manufacturer of high-end tiled stoves costing an average of 86,000 Swedish kronor ($7,700). The stoves can keep a room warm for 24 hours because of its intricate construction using different channels that hold and distribute the heat.

“During the pandemic, people started to invest more in their homes. That has now of course escalated,” said Jesper Svensson, owner and managing director of the company that’s located less than an hour drive from Sweden’s biggest nuclear reactor.

Orders have surged more than fourfold, and customers now have to wait until March for delivery, compared with as little as four weeks a year ago.

For many Europeans, the key concern is doing whatever it takes to stay warm in the coming months. The worry has become ever more pressing as the winter chill gets nearer, and the desperation for heat could create health and environmental issues.

Read more: People in Poland Are Burning Trash to Stay Warm This Winter

“We are worried that people will just burn what they can get their hands on,” said Roger Sedin, head of the air quality unit at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, warning against poor ventilation and trying to burn wet firewood. “We can see very high pollution levels when you have people burning wood who don’t know how to do it correctly.”

Particulate matter can end up deep in the lungs and cause heart attacks, strokes and asthma, he said, adding that the risk is particularly acute in urban areas.

“You need to think about your neighbors,” Sedin said.

Inexperience is also evident in Germany, where the country’s association of chimney sweeps is dealing with a flood of requests to connect new and old stoves, and customers are inquiring about burning horse dung and other obscure fuels.

There are also signs of hording. In France, Frederic Coirier, chief executive officer of Poujoulat SA, which makes chimney flues and produces wood fuels, said some clients have bought two tons of wood pellets, when less than one ton is normally enough to head a home for a year.

“People are desperate for wood, and they are buying more than usual,” said Trond Fjortoft, founder and CEO of Norwegian wood seller Kortreist Ved. “Usually it happens when it starts to get cold, ‘someone says, oh we should order some wood.’ This year, that started in June” — around the time Russia slashed gas supplies.

In Berlin, the crisis creates unsettling echoes of the desolation following World War II. With fuel in short supply, residents chopped down nearly all the trees in the central Tiergarten park for heating.

While Berliners aren’t going to such extremes now, concerns about staying warm are widespread. Engelke not only put up an extra security gate to protect logs, coal briquettes and heating oil, he also had to stop taking on new customers.

“We’re looking ahead to winter with great concern,” he said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

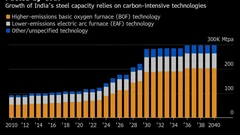

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals