How to Tear Down a Nuclear Power Plant in Vermont and Bury It in Texas

(Bloomberg) -- People get nervous around nuclear power plants, which means that demolishing one has to be done very, very carefully. The Vermont Yankee power plant sits on the bank of a scenic river in Vernon, Vermont, and for more than 40 years, the atoms split in its reactor generated as much as 70% of the state’s electricity. But then natural gas prices undercut the plant’s electricity and local anti-nuclear protesters worried about safety marched with signs that read “Hell no, we won’t glow.” Entergy Corp., the big Louisiana-based power company that owned Vermont Yankee, shut the plant down in 2014. It then sold the site to NorthStar Group Services Inc., which is now responsible for the decommissioning.

Now the entire plant is being knocked down and cut apart, including the cooling towers that looked exactly like the ones where Homer Simpson works. Most of the demolished plant is headed south to Texas and possible plans for the site include a solar farm or sports fields. Decommissioning the plant, which NorthStar estimates will cost about $600 million, is being paid for by a massive trust fund that the plant’s customers contributed to when the plant was generating electricity.

The problem

The radiation that permeates the buildings and equipment on the grounds of a nuclear power plant make tearing one down especially tricky. Spent nuclear fuel remain dangerous for thousands of years, emitting radiation that interferes with bodily functions like creating new cells. Even brief exposure to an unshielded fuel rod would destroy a person’s central nervous system. If you tried to walk across a room towards a fuel rod fresh out of a nuclear reactor, “You'd be dead before you got there,” said Chris Gadomski, a nuclear industry analyst at clean-energy research group BloombergNEF.

So NorthStar can’t just drop off rubble and steel at the local dump. Any material that gives off even trace amounts of radiation has been loaded onto a train and shipped off for burial deep in the red clay of West Texas, where a NorthStar subsidiary operates a disposal site for low-level radioactive waste. NorthStar has already moved 467 rail cars with more than 54 million pounds to its disposal site in the Lone Star state. “When in doubt, to Texas it goes,” said NorthStar chief executive officer Scott State.

The stakes

Vermont Yankee is one of 13 US reactors that have shut down in the past decade as costly nuclear plants struggled to compete against cheap natural gas. All of them will need to be dismantled and NorthStar, which is owned by private equity firm J.F. Lehman & Co., is one of a handful of companies that specialize in these complex projects.

This decommissioning job is happening at a unique moment for the nuclear industry, as growing pressure to fight climate change has sparked a reevaluation of a power source that generates carbon-free energy around the clock. Even some environmental groups that long expressed concern about the potential impact of a nuclear accident are now more worried about the very real impacts of climate change. Michigan tried to restart a 51-year-old plant that shut down in May, and California just passed legislation to delay the scheduled closure of a plant built right on the coast of the Pacific Ocean.

But to maintain that support, decommissioning jobs like Vermont Yankee must go smoothly. Even after the fuel rods are loaded into their casks, workers have potential risks to avoid, such as the radioactive dust that can be produced when workers cut apart materials like the reactor.

An accident would be a setback for the entire industry, said CEO State. "As a society, you can't just build things and leave them to decay," said State.

Why it’s tricky

Radiation complicates every step of demolition. Every worker or visitor to the site wears a meter around their neck that measures total exposure and can warn of overexposure. A visit to the building that held the reactor – which is now cut apart and buried 100 feet deep in Texas – requires passing through an airlock and three different full-body scanners to ensure nothing radioactive leaves the site.

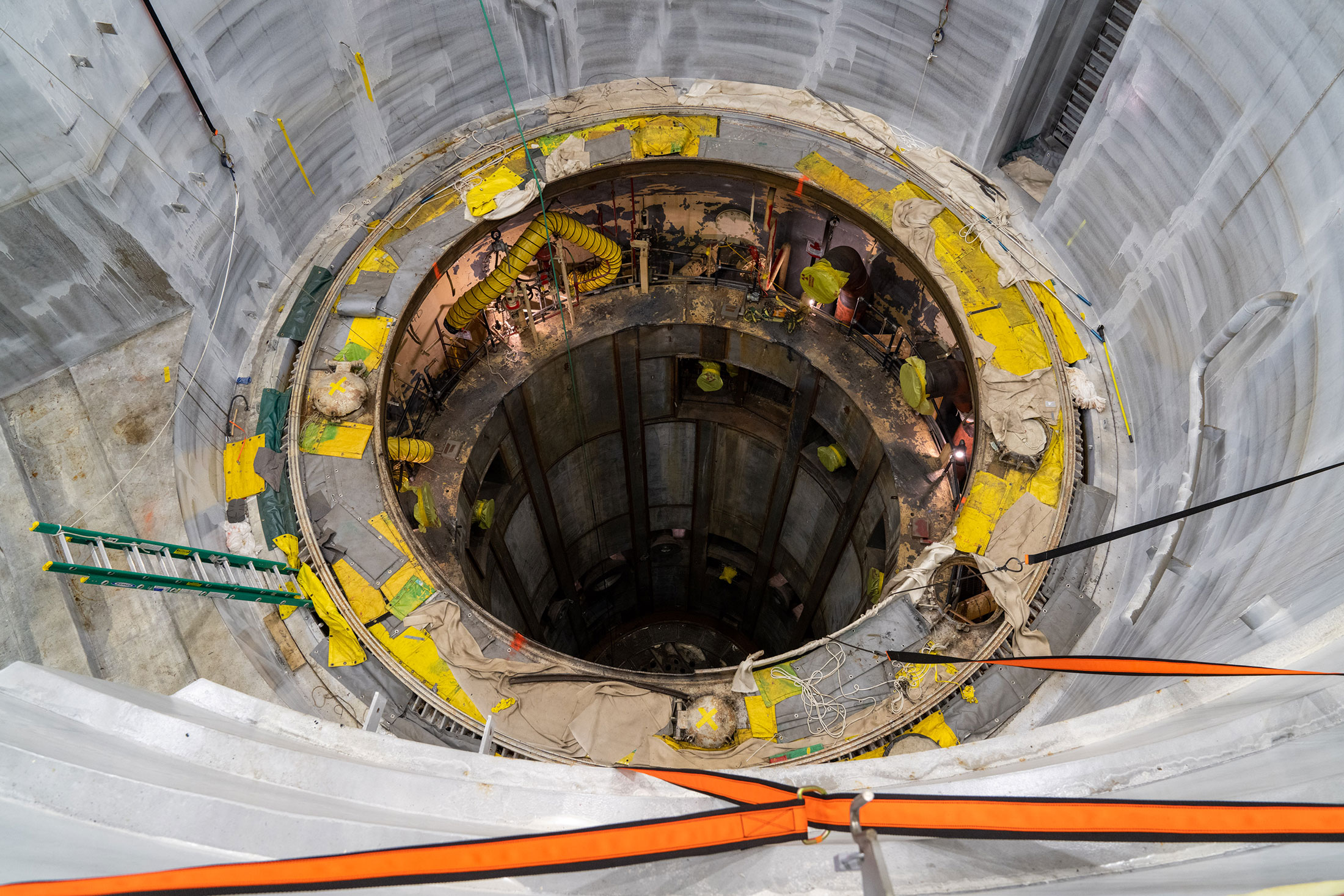

Some workers wear yellow suits and big helmets for protection that bring to mind the government agents in They use torch cutters to slice apart a reactor pump the size of a pickup truck. And some pieces of equipment are lowered into what used to be the spent fuel pool and cut apart underwater in order to contain any radiation.

Speaking of water: there’s 1.2 million gallons that were used in the reactor that also have to be pumped into tanker trains. After transport by rail to Texas, that water— almost enough to fill two Olympic-sized swimming pools— will be mixed with the chemical bentonite to turn it into a solid so it can be safely buried for perpetuity alongside the reactor and other material from the plant.The most difficult piece of the Vermont Yankee puzzle, however, is the nuclear rods that actually produced the heat that generated all that electricity. Known as “fissile material” in the industry, that high-level waste is the most dangerous part of a nuclear plant and can only be moved around in big metal casks so heavy they require specialized transporters that can lift hundreds of tons at a time. A total of 58 metal casks stand in neat rows at Vermont Yankee near the river behind a tall barbed-wire fence. The casks are designed to contain the radiation emitted by the rods and withstand natural disasters or attacks. Since the first casks were loaded more than 30 years ago, there has never been a radiation release that hurt anyone, according to the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The problem is there’s nowhere in the U.S. that will take those rods. President Barack Obama shut down plans in 2009 for Yucca Mountain in Nevada to become the nation’s sole repository for nuclear waste. Since then, nuclear plants just keep their spent fuel onsite—which means the Vermont Yankee site could be host to those radioactive rods for a long, long time. A report that lays out redevelopment possibilities for the site shows the casks separated from the rest of the site by 150 meters, hidden behind a curtain of trees.

Why there’s hope

When Entergy shuttered Vermont Yankee and sold the site to NorthStar, it said the property would be decontaminated and restored by 2030. NorthStar now says the work will be done and the location released by the end of 2026. That’s good news for nuclear power’s reputation.

Not every piece of the plant is radioactive: steel and concrete that doesn’t give off a radioactive signal can even be recycled. And since NorthStar actually took over ownership of the plant from Entergy, it gets to decide what to do with the site when it’s done. The current plan is to gift the 125-acre site to the town of Vernon, which has considered plans for the grounds including a solar farm, a natural gas plant, sports fields or housing.

“We’re going to do this in probably half the time a project like this has ever been done before,” State said. “If you come back here in two years you’ll see an empty field.” Except for the metal casks full of radioactive fuel rods, of course.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

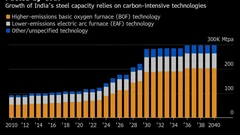

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture