EPA Isn’t ‘Knocked Out,’ But Doing Its Job Just Got Much Harder

(Bloomberg) -- The Supreme Court ruling Thursday that curtailed the Environmental Protection Agency’s flexibility to curb power-plant emissions on a systematic basis is setting the stage for a piecemeal approach to the issue. But the decision didn’t erase the agency’s ability to regulate greenhouse-gas pollutants more broadly, nor did it leave it entirely toothless in the fight against climate change.

The agency still maintains the ability to regulate emissions from individual power plants, but now must move forward with more caution. Even before the ruling, EPA officials were planning new rules to regulate plant emissions, taking a narrower approach that would be focused squarely on coal- and gas-fired power plants, without bringing in non-emitting renewable electricity.

Now it seems likely that the narrow approach will be the clearest path forward after the Supreme Court stripped the agency of broader oversight.

The EPA can still force significant emission reductions, “but it will be more costly and less effective,” said Jay Duffy, an attorney with the Clean Air Task Force.

The 6-3 ruling interpreting the US Clean Air Act was quickly celebrated by fossil-fuel companies and their allies, while it was immediately blasted by climate advocates. This much is clear: The decision to clip the EPA’s powers to rein in planet-warming pollution from power plants comes despite a shrinking window to prevent the worst consequences of climate change. The ruling will make it much harder for President Joe Biden to fulfill his pledge for the US to halve greenhouse-gas emissions by the end of the decade, though it is unlikely to stop the electricity sector’s ongoing shift away from fossil fuels as market forces drive the transition to clean energy.

“Regulating greenhouse-gas emissions from the electricity sector, and point-source emitters like power plants in particular, is arguably the `lowest hanging fruit’ in mitigating climate change,’’ said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “If we can’t make rapid progress on the easiest aspects of emissions reductions in the short term, that does not bode well for reaching any number of optimistic climate targets in the coming decades.”

Other EPA Authorities

Still, there was some relief from climate advocates that the ruling was focused on the power-plants issue and didn’t place further limitations on the EPA.

“This is a very limited decision,” Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of Columbia University's Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, said in an email. “It doesn’t undercut EPA's other authorities to regulate greenhouse gases, such as imposing limits on motor vehicles (the largest source of GHG emissions), factories, and oil and gas production. EPA also has other tools to control pollution from coal-fired power plants.”

Read more: Key excerpts from the decision and the dissent

In the ruling, the majority said that while the EPA can regulate power-plant emissions, the agency can’t try to shift power generation away from fossil fuel plants to cleaner sources, as former President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan sought to do. Writing for the court, Chief Justice John Roberts said Congress needs to speak more explicitly to give an agency that much power.

The White House issued a statement indicating Biden will continue to push forward using whatever regulatory power remains. The EPA said it was “reviewing” the decision.

“EPA is committed to using the full scope of its existing authorities to protect public health and significantly reduce environmental pollution, which is in alignment with the growing clean energy economy,” the agency said in a statement.

How Experts View the Ruling

Some experts warn that won’t be easy.

“Today’s ruling limits the tools available to the EPA to sensibly reduce power-plant emissions using cost-effective strategies that reflect the realities of an electric power system that is increasingly dynamic and diverse,” Jeff Dennis, general counsel and managing director of Advanced Energy Economy, a national business association that advocates for clean energy, said in a statement.

Duffy, of the Clean Air Task Force, said the EPA still has “ample authority to set stringent standards based on pollution-control technologies such as carbon scrubbers and gas and hydrogen co-firing.”

“These technologies can reduce emissions to near zero and would put the costs of pollution cleanup on industry instead of public health and the environment,” he said.

The question now is how aggressively the EPA will use the authorities it still has.

“This approach that’s left, while it can be quite effective, it’s going to be less flexible,” David Doniger, senior strategic director of the climate and clean energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said during a media call with reporters. “The Supreme Court didn’t knock the EPA out of the whole business of regulating carbon.”

Options now available to the agency could include demanding efficiency upgrades at plants or the addition of carbon-capture technology and even changes in the fuel used at the plants. For instance, a coal power plant’s greenhouse gas emissions would go down if the facility were compelled to burn some natural gas at the same time, an approach called co-firing. And carbon dioxide emissions tied to a gas plant also could shrink if the facility swapped some of its fuel for cleaner-burning options such as hydrogen or biogas collected from landfills, farms and wastewater facilities.

Even a modest co-firing standard for coal plants could rapidly and significantly reduce carbon dioxide emissions, according to Resources for the Future research. That analysis found that if the EPA sets a performance standard requiring 20% co-firing at individual coal plants, cumulative emissions would be 16% lower between 2022 and 2030.

But as the EPA makes new regulations it is sure to be looking over its shoulder at the court, which signaled a willingness to undercut the agency's authority.

As Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her dissent: “The Court appoints itself—instead of Congress or the expert agency—the decision-maker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

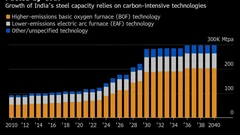

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture

Blackstone’s Data-Center Ambitions School a City on AI Power Strains

Chevron Is Cutting Low-Carbon Spending by 25% Amid Belt Tightening