Cleaning Up Airline Travel Is Going to Be Really Expensive

(Bloomberg) -- We’re probably going to have to fly less. And when we do board a plane, it’s going to cost more — a lot more, one way or another.

Those are the conclusions of a new report by the nonprofit International Council on Clean Transportation, which analyzed how the airline industry could cut emissions in line with global climate goals. People will “still be able to fly in the future and do so with a clean conscience,” said Brandon Graver, a co-author of the study and a senior aviation researcher at the organization. “But it’s going to be expensive, and we need to have discussions on who is going to pay for that.”

The airline industry’s main lobby group set a net zero emissions target for 2050 last year, and the United Nations agency overseeing the industry will set its own climate goal later this year. In 2015, more than 190 countries agreed to reduce emissions to a level that would keep future warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, ideally to 1.5 degrees, compared with preindustrial levels. (Progress update: Global surface temperatures have risen 1.1 degrees to date, on pace to hit about 3 degrees this century.)

Aligning aviation with the Paris goals “is possible but will require significant ambition and investment,” warned the new report. In every scenario, the largest pollution reductions come from the same source: sustainable aviation fuels, or SAFs. The most ambitious path calls for alternative fuels to comprise 17% of aircraft fuel use by 2030 and 100% by 2050. In a more moderate scenario, SAFs only made up 3% of aircraft fuels by 2030 and 50% of fuel use by mid-century.

Sustainable fuels are currently a lot more expensive than traditional jet fuel. The report suggests that government policies could encourage the use of SAF by offering tax breaks and other incentives while also making fossil fuels more expensive. Either way, the airlines will likely pass at least some of the higher costs on to passengers and customers.Compared to a status-quo, do-nothing pathway, the most aggressive carbon-reduction scenario leads to a 7% drop in passenger traffic and a 22% increase in ticket prices by 2050, driven by a 70% rise in fuel costs. Even then, the airline industry would only be consistent with a 1.75-degree warming target, still higher than the Paris ideal.

The aviation industry is “a really hard sector to decarbonize,” if not the most difficult one, said Samantha Gross, director of Brookings’ Energy Security and Climate Initiative and who was not involved in the study. Consequently, “it will be among the last and most expensive and hardest emissions to eliminate.”

The report also outlined continuing improvements in airplane designs and flight patterns that could cut the climate pollution of each flight. Years down the line, the report predicted electric planes or aircrafts running on hydrogen could make up a growing share of short-distance flights.

Those technologies don’t really exist yet, said World Resources Institute research analyst Clea Schumer. “We don’t know when they will,” she said. “We need something fast” — like SAFs — “that can be dropped into existing infrastructure.”

Another way the airline industry could claim emissions reductions is through the use of carbon offsets, which involve investing in climate friendly programs that may prevent emissions releases or reduce emissions directly. But offsets vary widely in quality and effectiveness. The ICCT study didn’t include offsets in its analysis.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

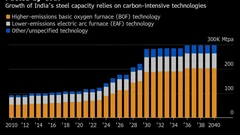

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals