China’s Solar Giants Have a Fix for Their Broken Supply Chain

(Bloomberg) -- The supply chain snarl that tripled the price of a key raw material for solar panels is about to get fixed, clearing the way for a renewed boom in the use of the clean energy technology.

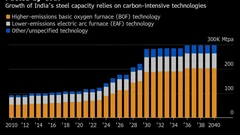

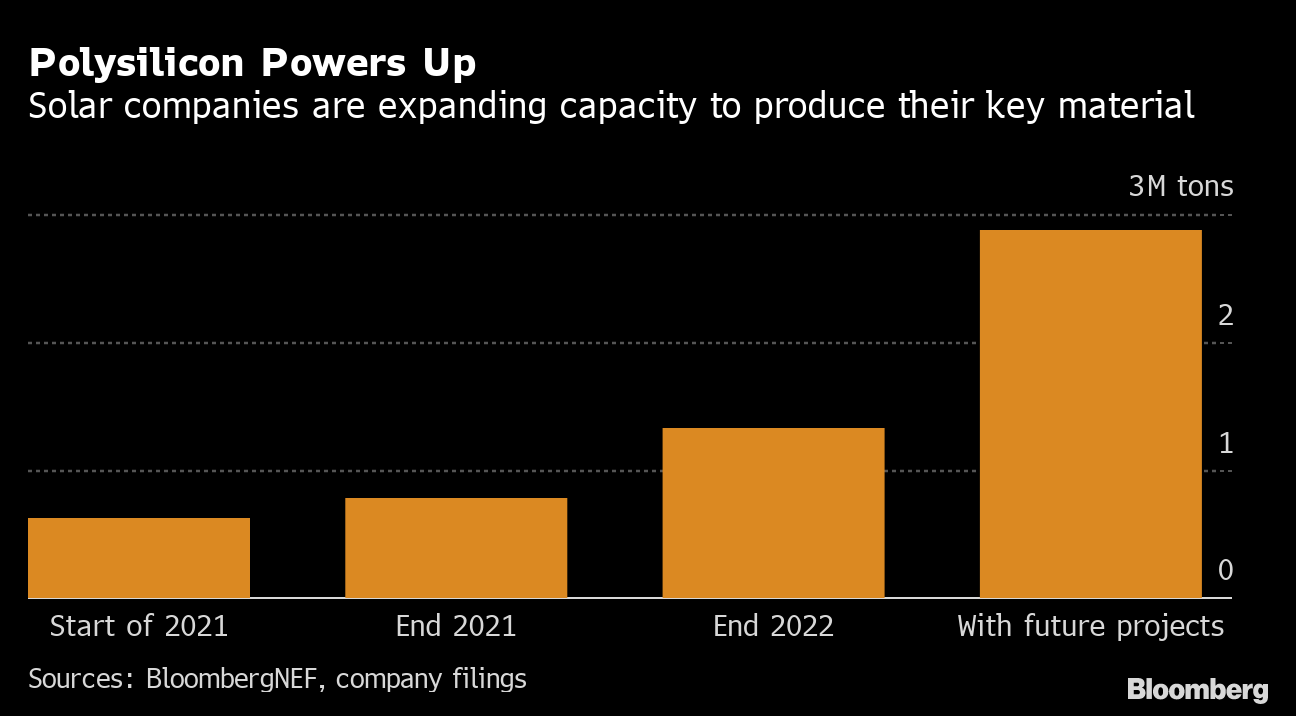

China is spending billions on new factories to produce polysilicon, used to make photovoltaic cells for solar panels. Global capacity has already been boosted by more than a quarter in the past two months, and it will double by early next year. That should help rein in prices of the material after surging costs slowed the pace of new renewables projects.

As component shortages to a squeeze on shipping drive up prices for everything from natural gas to beef, polysilicon is an example of how some supply woes will likely prove transitory. It also shows how China is using its industrial heft to ensure its continued dominance in solar, a sector that’s key to fending off the worst impacts of climate change.

The multi-billion dollar expansion of polysilicon capacity will “help to remove a key bottleneck to the solar value chain,” said Tony Fei, an analyst with BOCI Research Ltd. “We expect solar panel supply to be vastly boosted in the coming years with declining prices, contributing to decarbonization of the global energy mix.”

Solar panels are made from ingots of ultra-conductive polysilicon that are sliced into razor-thin wafers, wired up into cells and then assembled into the equipment that’s mounted on rooftops or across vast energy farms. After years of prices falling as companies opened newer and more efficient polysilicon plants, the raw material skyrocketed last year as a jump in demand overwhelmed existing manufacturing capacity. By late 2021, polysilicon was trading at a 10-year high.

Read more: Solar Power's Decade of Falling Costs Is Thrown Into Reverse

Prices have already come off 17% since November after Tongwei Co., Daqo New Energy Inc. and GCL-Poly Energy Energy Holdings Ltd. — among the key global producers — opened new plants or lines with combined capacity of 160,000 tons a year, adding to a current global fleet of about 620,000 tons, according to BloombergNEF data. Another 550,000 tons of capacity is under construction, most of which will be online by the end of this year.

“Polysilicon prices will remain elevated in the first half of 2022 and then nosedive to a historic low in 2023,” said Dennis Ip, an analyst with Daiwa Capital Markets. In turn, that will drive down costs of solar modules and deliver strong growth in installations, he said.

Tongwei and GCL shares both fell more than 2.2% Tuesday, while South Korean polysilicon maker OCI Co. dropped 1.9%.

Beyond the projects already under construction, another 1.5 million tons of new capacity has been announced, including more than 850,000 tons last month alone, according to BloombergNEF data and company filings.

One reason for that December surge was China’s decision to loosen energy-consumption rules for renewable power-related materials, according to BOCI’s Fei. Several recently announced projects have also vowed to use wind and solar to power their polysilicon production lines, which will ensure they avoid scrutiny from government watchdogs investigating high-polluting industries.

Many of the new projects are also being located outside of Xinjiang, home to nearly half of existing global production. That factor has put the solar industry in the crosshairs of global trade wars, as governments including the U.S. bar products from the region because of accusations of forced labor and other efforts to suppress the predominately Muslim Uyghur minority. China’s government has repeatedly denied those allegations.

Read more: China’s Solar Industry Is Slowly Shifting Away From Xinjiang

Fixing polysilicon shortages is key for the solar industry because it’s the most difficult step in the supply chain in which to add capacity. New plants can take 18 to 24 months to come online, followed by a lengthy ramp-up process, compared to under a year for less complicated materials or manufacturing processes.

“Polysilicon is the one step that requires a long time to build capacity,” said Yali Jiang, an analyst with BloombergNEF in Hong Kong. “Building wafer, cell and module plants is very fast nowadays.”

By the end of this year, solar companies will be able to produce enough polysilicon to allow for more than 500 gigawatts of capacity to be installed annually, which compares to a total of about 144 gigawatts installed globally in 2020. BloombergNEF estimates about 455 gigawatts need to be added every year through 2030 for the world to be on pace to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

“We’ve seen several countries where projects are on hold or where they’re not going forward because of high prices,” said Johannes Bernreuter, head of polysilicon market intelligence firm Bernreuter Research. “Once the polysilicon bottleneck is removed and prices come down again, it will incentivize even more dynamic demand.”

(Updates to add share price moves in 8th paragraph.)

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

House Committee Says It Finds Evidence of ‘Climate Cartel’

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid