The Climate Future Just Changed: Eight Predictions for 2030

(Bloomberg) --

This portrait of life in 2030 would have seemed like the hopeless dream of a climate optimist just a few weeks ago. Today it’s at least a little more plausible.

The Inflation Reduction Act, which just passed through the House after approval by the Senate last week, is a climate investment with no parallel in US history. The spending package of $374 billion, expected to be signed into law by President Joe Biden, is aimed at turbocharging the largest economy’s belated shift to clean energy. It also has controversial sweeteners for the oil and gas industries.

As the bill made its way through Congress, asked experts from across the climateverse to participate in a thought exercise: Imagine it’s 2030. What’s an aspect of the American future that wouldn’t have been possible without this legislation?

Of course, there’s a chasm between the law on paper and how the provisions in its 700-plus-pages are implemented in coming years. As Ryan Panchadsaram, a partner at the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins and previously the deputy chief technology officer in the Obama administration, puts it: “There are rules and regs that civil servants craft and enforce. Are they actually going to lead to the right thing?”

With that caveat, here are eight mostly hopeful visions of the (near) future from climate watchers, tech investors and activists.

Improved air quality starts at home

Saul Griffith of Rewiring America, a nonprofit that promotes the electrification of US communities, points to tangible health benefits like lower rates of respiratory illness as a likely outcome of the IRA by 2030. The law provides generous rebates for homeowners to switch from gas to induction cooktops, which would cut harmful indoor pollutants. The house of the future will be fully electric, Griffith says, with heat pumps for water and space heating.

Healthier neighborhoods delivered by (electric) trucks

As the longtime chair of the California Air Resources Board, Mary Nichols served as the state’s chief climate regulator between 2007 and 2020. One of the biggest potential transformations of life in 2030, she says, is the electrification of highly polluting heavy trucks that service ports and sprawling logistics centers that are typically located in low-income communities of color. “That’s key to at least beginning to take environmental justice seriously,” says Nichols. “Electric cars always grab the headlines, but it is actually the trucks that make the money and they also make the most emissions.”

More transparent supply chains

The IRA includes a two-part, $7,500 credit for clean vehicles. Cars qualify for half of it if key battery materials are mined in a country that the US has a free-trade agreement with or if they’ve been recycled in a North American facility. They qualify for the second half if the battery is largely assembled in North America. These provisions will incentivize carmakers to show “the proof of where their critical minerals and production happened,” says Ellen Carey, vice president for global policy and public affairs at Circulor Ltd., which makes supply-chain-tracking software.

Cities that reach 100% electrification

Electrification won’t just happen at the level of the individual home or neighborhood, says Donnel Baird, the founder of BlocPower, a New York-based startup that carries out green retrofits of buildings. It will occur at the urban scale, with a boost from the new legislation. “There’s something like 20 to 50 million American buildings that haven’t had energy upgrades in like 40 years,” he says. “This bill is just going to let them leapfrog over natural gas, coal and oil to clean electricity.”

Slower-rising seas…

Jean Flemma, co-founder of the think tank Urban Ocean Lab, says the emissions-cutting actions enabled by the IRA may result in a slowdown in sea-level rise. That could end up delivering a lifeline to vulnerable coastal communities. “Slowing the rate of sea level rise is incredibly important from an environmental justice standpoint,” she says, noting the law provides $2.6 billion for coastal resilience. “When you look at New York and other cities, communities of color and lower resource communities are the ones that are at greatest risk from sea-level rise from increasing storms that are coming from climate change.”

…and continued rising temperatures

Daniela V. Fernandez, founder and chief executive officer of the Sustainable Ocean Alliance, says the IRA, while “promising and exciting” in parts, isn’t alone up to the urgent task of keeping global warming under the Paris Agreement threshold of 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit). The rise in global average temperatures already hovers at 1.2°C above the pre-industrial era, and there’s little doubt that Americans in 2030 will be experiencing even higher temperatures. “It sadly falls short of what this moment requires,” says Fernandez. She wants a “declaration of a climate emergency and from the vantage point of the energy production transition, a complete divestment from fossil fuels.”

An entrenched green economy

With incentives to build renewable energy, make agriculture more efficient, promote EVs, capture carbon and much else, the IRA should bring many more Americans into the clean energy economy by the end of the decade. Because of that, predicts Trevor Houser, a partner at the research firm Rhodium Group, back-tracking toward emissions-intensive industries will become less and less desirable or feasible. “The most successful vision of this,” he says, is that domestic economic growth and investments “fundamentally shift the politics of climate and clean energy in the US because there’s a broad and diverse set of stakeholders with equity in that transition.”

Leah Stokes, a political science professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, predicts that the legion of employees whose livelihoods come from clean-tech sectors kickstarted by the climate bill will create a viable political constituency by 2030. “When we have big manufacturers employing people in every state and district in this country in clean energy, that’s going to be the powerhouse when it comes to our energy policy from the federal government,” says Stokes, who is also an advisor for the lobbying group Evergreen Action. “It’s a total game changer.”

Next-generation climate politics

Julian Brave NoiseCat, a climate and Indigenous advocate, hopes that by 2030 we’ll look back at the IRA as a first step. The bill gets the US “sufficiently down the road politically,” he says, by cutting emissions so that better government policy can follow later this decade. “I think there is legitimate concern that communities that were impacted by polluted land and left behind by the fossil fuel economy are not getting sufficient investment in this bill to benefit from a cleaner economy,” he says. “This bill marks a close in generational politics on climate change.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

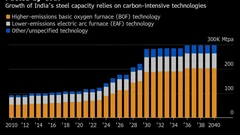

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture

Blackstone’s Data-Center Ambitions School a City on AI Power Strains

Chevron Is Cutting Low-Carbon Spending by 25% Amid Belt Tightening

Free Green Power in Sweden Is Crippling Its Wind Industry