What Russia’s war in Ukraine means for efforts to cut emissions

(Bloomberg) -- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions have effectively taken the world’s fourth-largest polluter out of the global battle to reach net-zero emissions, while European metal imports may also get dirtier.

A multibillion-dollar project that would help reduce emissions and modernize Russia’s biggest aluminum producer is facing challenges, according to people familiar with the situation. Two new plants that would have helped the country’s biggest iron ore miner produce greener raw material for steel to be exported to Europe face likely delays, separate people familiar said.The potentially stalled infrastructure upgrades threaten to derail any nascent steps Russia was taking to make good on President Vladimir Putin’s pledge last year to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. The Kommersant newspaper said last month Russia is no longer able to meet its emissions reduction targets for mid-century. That are direct implications for Europe's climate ambitions as well, as the energy transition drives demand for everything from nickel for new electric vehicle batteries to copper for power grid upgrades and steel for new more efficient buildings.

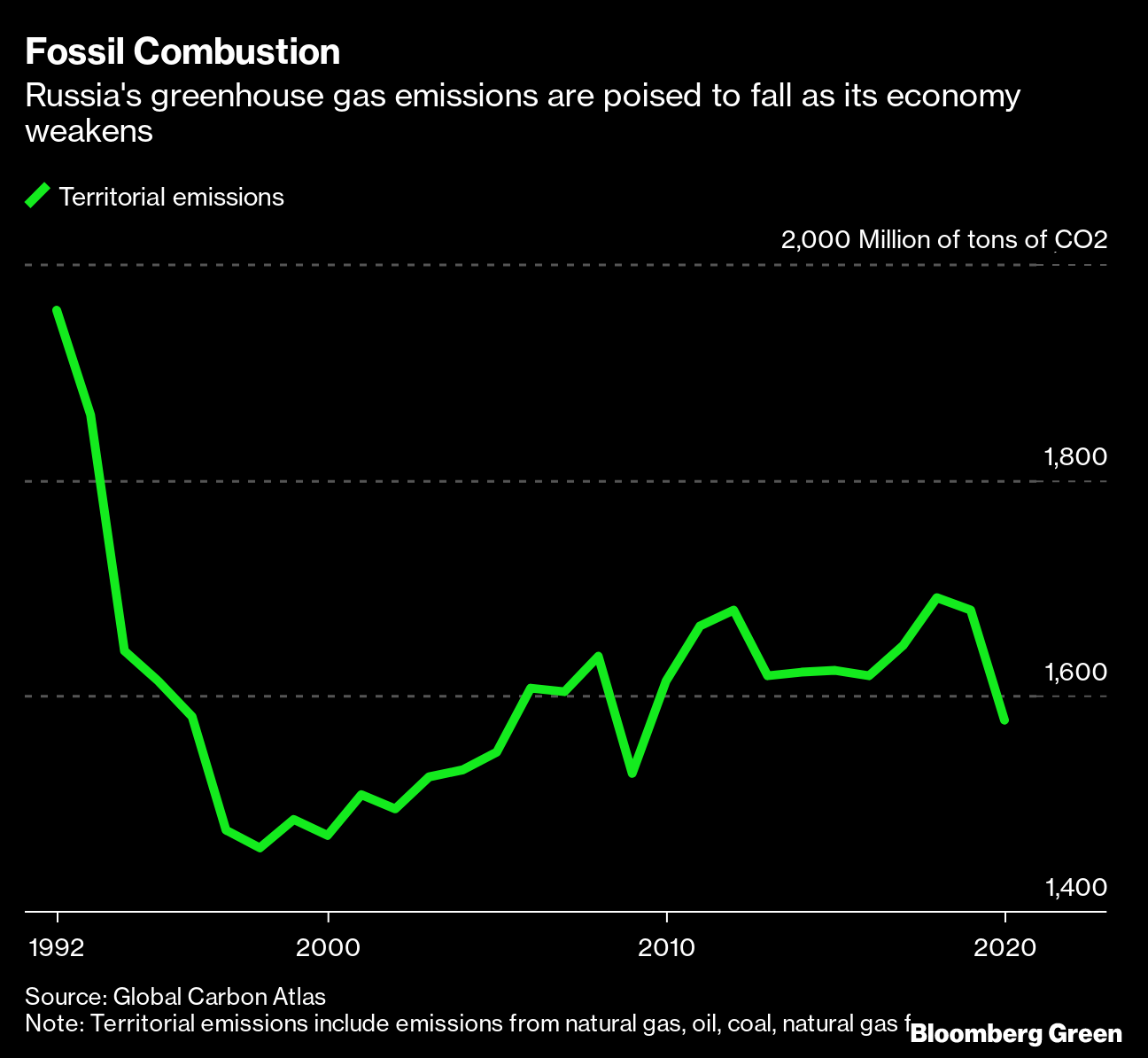

Russia’s overall emissions are poised for a drop this year as its economy contracts, but industries that survive won’t be able to cut carbon pollution as quickly and may even become dirtier with time. External pressure to lower emissions, such as Tesla Inc.’s search for cleaner nickel or the European Union’s move to impose a carbon levy on imports such as steel, has faded as foreign countries and companies spurn Russian goods.

“Those incentives to develop renewables, to develop energy efficiency — they will simply disappear,” said Tatiana Mitrova, a non-resident fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “Why should you invest in energy savings if fuel is so cheap and at the same time you do not have access to energy-efficient technologies any longer?”

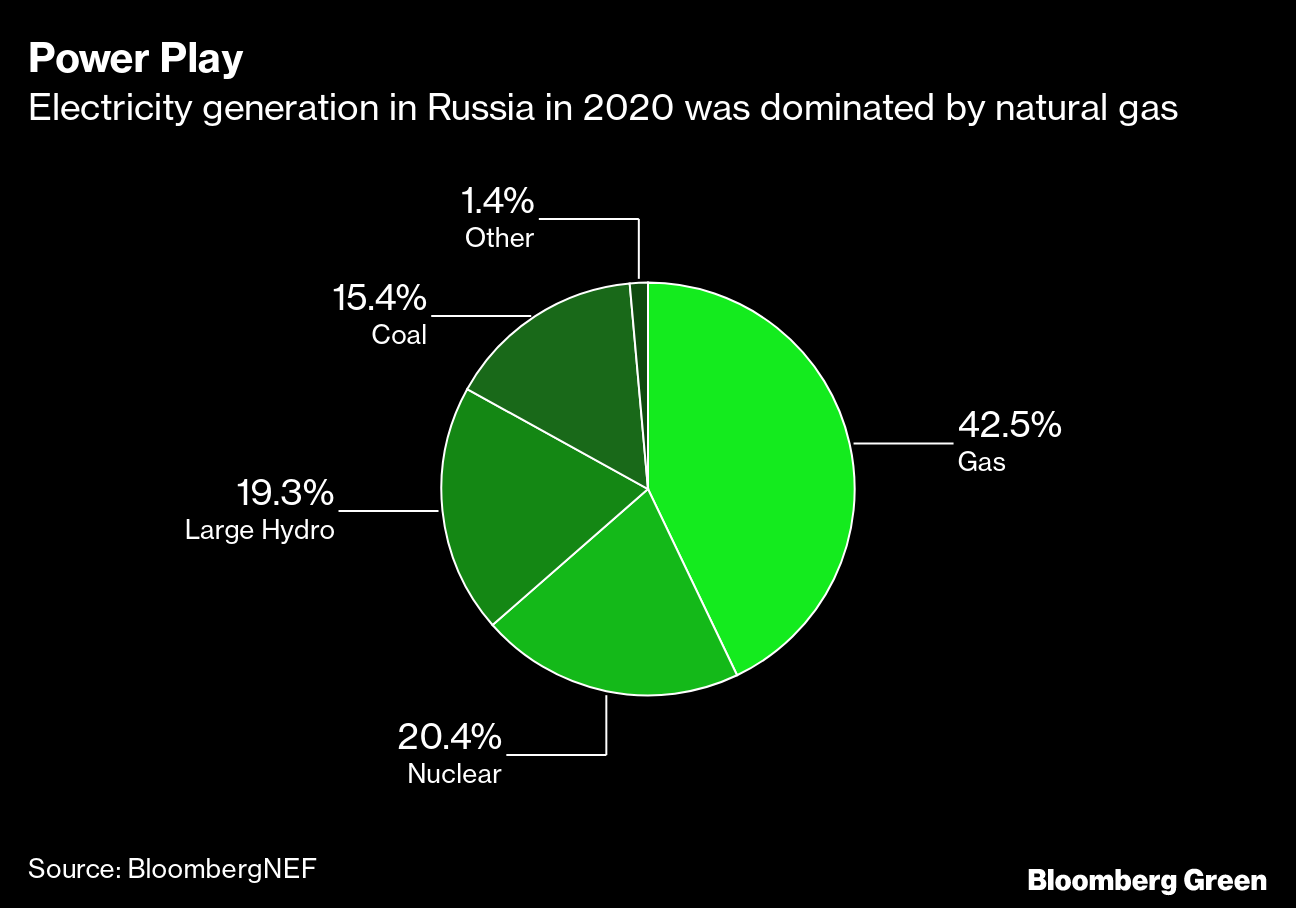

Russia’s economy remains deeply reliant on fossil fuels, with coal and gas generating about 58% of the country’s power needs, according to clean energy researchers at BloombergNEF. Hydropower and nuclear were responsible for almost 40% in 2020, with wind and solar barely registering in the country’s energy mix.

The country had been making progress in cutting emissions from production of iron and steel, which is responsible for about 6% of its greenhouse gases. Steelmakers spent tens of billions of dollars to upgrade and rebuild old Soviet facilities over the last two decades, in many instances relying on foreign expertise and technology. But repairing and further improving those plants has now become more difficult under sanctions.

One way to significantly reduce pollution from steelmaking is to produce a type of iron known as hot-briquetted iron, or HBI, which generates 35% to 40% less carbon dioxide than is emitted by traditional processes like coal-based blast furnace steelmaking.

Metalloinvest Holding Co., Russia’s biggest iron ore producer, in October signed a $600 million contract to build a new HBI plant at its Lebedinsky mine. That project is likely to be put on hold, according to people familiar with the situation who asked not to be named. Another $540 million HBI plant planned for the company’s Mikhailovsky mine, which was under construction, is in a similar situation.

Metalloinvest, already the world’s biggest HBI producer, had planned the new facilities to supply customers in Europe, which are set to face higher charges for importing emissions-heavy raw materials under coming regulations aimed at eliminating the continent’s net greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century. Metalloinvest declined to comment.

Some other steelmakers were also considering boosting their HBI output to make Russian steel cleaner, according to a person at a top company in the industry who asked not to be named. But those plans are now dead even before they were made public, two separate steel executives said.“If the current geopolitical situation and sanctions imposed remain in place long-term, that could make it impossible to use high-end technology needed to implement projects required to achieve climate goals,” said Alexander Shevelev, chief executive officer of Severstal PJSC, one of Russia’s leading steelmakers. The company will try to stick to its plan of cutting emissions 10% by the end of the decade, he said.

The same problem has hit the Russian aluminum industry, which accounts for 10% of the global market. United Co. Rusal International PJSC, Russia’s main producer of the metal, isn’t under sanctions, but it faces logistical challenges and a shortfall of imported alumna — the raw material needed to make the metal — because of the war and a ban on exports from Australia. That may affect the company’s $5 billion of planned investments to upgrade its smelters.

“Rusal continues the program of environmental restructuring of four aluminum smelters in Siberia," its spokesman said. "Changes of some parameters of the project are possible. But the goal remains the same: super-modern production facilities will appear on the site of workshops built in Soviet times, and the environmental situation in our cities will become better.” The company said on March 30 that Russia’s plan to change how domestic metals prices are regulated may hurt the company’s profitability, which could push back the projects.

To be sure, some projects still appear to be going forward despite sanctions. MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC, the world’s largest producer of refined nickel used in batteries, said this month a roughly $4 billion plan to build a sulfur capture facility at a copper plant is proceeding and scheduled to be completed in 2023. Although the revamp won’t reduce carbon pollution, it will lower local emissions of sulfur dioxide.It’s still too early to tell how exactly the sanctions will impact Russia’s economy, and, in turn, emissions. The World Bank estimates that gross domestic product could shrink more than 10% this year and the country’s central bank has warned of a “ reverse industrialization” that will increase waste and pollution.

There are signs that the immediate hit could lower Russia’s pollution. For example, jet fuel demand has plunged at Russian airports since the Ukraine invasion, according to French geoanalytics company Kayrros SAS. But Kayrros researchers also estimate that carbon-intensive cement production and coal-fired power generation are mostly in line with seasonal averages.

Meanwhile the war is having other negative consequences on global emissions. A push by Western countries to wean themselves off Russian fossil fuels has spurred a boom in the coal market. Surging energy prices are also boosting demand for dirty fuels, including gas, in other parts of the world.

READ MORE: Russia’s War Is Turbocharging the World’s Addiction to Coal

Still, there’s a chance that sanctions could leave more hydrocarbons in the ground. Russia’s oil production this year may drop by as much as 17% due to international restrictions, Finance Minster Anton Siluanov said this week. The U.S. has so far refrained from placing limits on the sale of onshore and conventional shallow-water drilling gear from companies like Schlumberger NV and Baker Hughes Co. Doing so could also reduce Russia’s ability to extract more oil and gas.

Uncertainties over how far the war will escalate hang over Russia’s companies. Executives are now operating in a wartime economy, rather than the increasingly globally integrated model of the past, making the declaration of future plans all but impossible. With businesses struggling to stay afloat, climate targets are hardly the most pressing issue.

Russian companies “do not understand the expectations of the state. One day they might announce termination of one of their key projects and the state says ‘you are a national betrayer,’’’ said Mitrova. “It's survival boats.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

House Committee Says It Finds Evidence of ‘Climate Cartel’

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid