A California Startup Now Offers a Full EV Battery in Just 10 Minutes

(Bloomberg) -- On a Wednesday afternoon in May, an Uber driver in San Francisco was about to run out of charge on his Nissan Leaf. Normally this would mean finding a place to plug in and wait for a half hour, at least. But this Leaf was different.

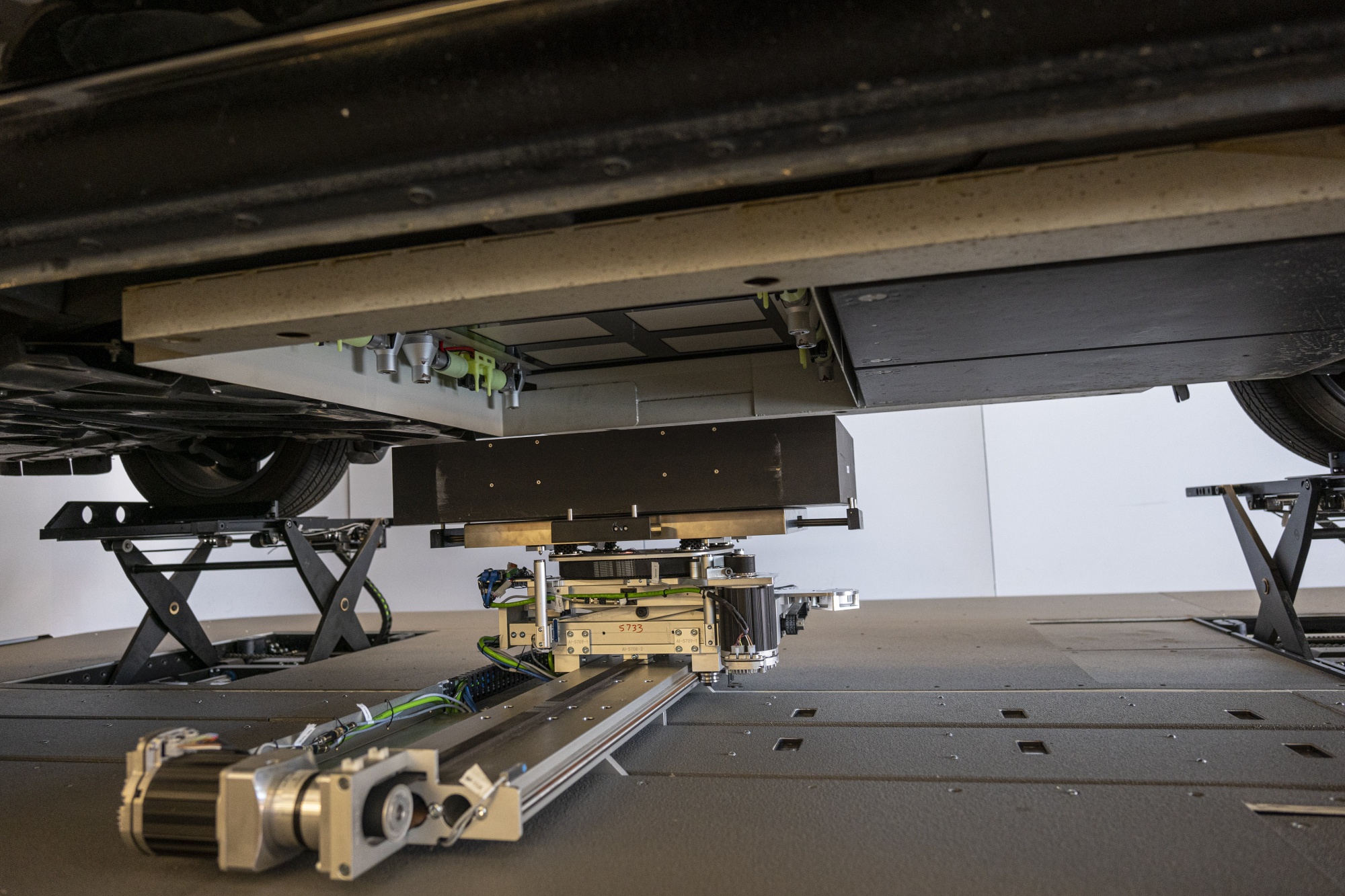

Instead of plugging in, the driver pulled into a swapping station near Mission Bay, where a set of robot arms lifted the car off of the ground, unloaded the depleted batteries and replaced them with a fully charged set. Twelve minutes later the Leaf pulled away with 32 kilowatt hours of energy, enough to drive about 130 miles, for a cost of $13.

A swap like this is a rare event in the U.S. The Leaf’s replaceable battery is made by Ample, one of the only companies offering a service that’s more popular in markets in Asia. In March, Ample announced that it had deployed five stations around the Bay Area. Nearly 100 Uber drivers are using them, the company says, making an average of 1.3 swaps per day. Ample’s operation is tiny compared to the 100,000 public EV chargers in the U.S.—not to mention the 150,000 gas stations running more than a million nozzles. Yet Ample’s founders Khaled Hassounah and John de Souza are convinced that it’s only a matter of time before the U.S. discovers that swapping is a necessary part of the transition to electric vehicles.

China, which is home to roughly half of the 7 million passenger EVs on the road as of last year, has more than 600 swapping stations and is on pace to have 1,000 by year’s end, according to a tally by clean-energy research group BloombergNEF. “They've already made the determination that swapping has to be a significant part of the solution,” says Hassounah, “We don't have enough deployment yet to realize that we need this in the U.S.” Even in China, however, where the swapping industry dwarfs that of the U.S., the technology is still only a small piece of the charging infrastructure.

In the U.S. most investment so far has gone into building faster plug-in stations and batteries that can accept power quickly without overheating. President Biden has proposed a target of 500,000 public chargers by 2030. His plan, which calls for scaling and improving fast-charging networks, makes no mention of battery swapping. Yet plug-in chargers come with limits that can’t be overcome simply by adding more. They are a burden on the power grid, expensive to build, and, even at their fastest, agonizingly slow compared to gas pumps.

Hassounah and De Souza founded Ample in 2014 and have raised about $70 million to date from investors including the venture arms of oil and gas giants Royal Dutch Shell plc and Repsol SA. They’ve spent the last seven years studying how to swap batteries in a cheap, vehicle-agnostic way and believe they’ve finally cracked it. For now they are focusing on ride-hailing fleets, as professional drivers have the most need for fast charging. Late last year, Ample entered a partnership with Uber to help coordinate with the the fleet management services that provide drivers with cars, insurance, and other services. On June 10, Ample announced a separate partnership with the fleet management service Sally, which specializes in making EVs available to ride-hailing and delivery drivers. The two plan to work to together to deploy EVs and swapping stations in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Sally aims to have hundreds of Ample-ready Kia Niro EVs running in the Bay Area by the end of this summer and to begin offering swapping to drivers in New York by the fall.

Sally co-founders Nicholas Williams and Adriel Gonzalez say the company chose to work with Ample because plug-in fast-charging options degrade batteries, come with high energy costs during peak use, and are too slow. “We had a supercharging concept that would probably do it in 30 minutes, but that was really too long for us,” says Williams.

Drivers in San Francisco rent Ample-ready EVs from fleet management services, just as they would for a combustion engine car, and pay the fleet manager for their swaps at the end of each week. The fleets then pay Ample by the mile for the energy, with no upfront fees for installing stations. The energy cost for fleets, according to Ample, is typically 10 to 20 percent cheaper than gas. “All the drivers that have used it have come over from gas vehicles,” says De Souza. “This is the first time they're driving an electric vehicle.”

Most EV charging in the U.S. happens at private chargers in driveways and garages, where drivers can use vehicle downtime to refill batteries slowly. But convincing Americans to ditch combustions engines and go electric means competing with the convenience of gas stations. The average fill-up, according to the NACS, a trade group for convenience stores and gas stations, takes 4.5 minutes, including the time it takes to pay. With a typical fill-up of about 12 gallons, a car that gets 25 miles per gallon can add 300 miles of range in less than five minutes. Doing the same in 40 minutes counts as ultra-fast for an electric charger. Ten such chargers on the side of a highway would need at least a megawatt connection, enough to power hundreds of homes.

Swapping, at least in theory, offers an elegant solution to the problem of re-charging EVs quickly without taxing the grid. Where an ultra-fast charger acts as a firehose, delivering a rush of energy on demand, Ample’s system works like a garden hose, constantly filling small buckets and handing them over a few at a time. So far, however, attempts at swapping in the U.S. have come to nothing. Tesla experimented with the technology in 2013 but soon abandoned it, opting instead to build its network of “Superchargers.” The startup Better Place, which planned to sell swappable batteries in its EVs, went bankrupt that same year, after raising nearly $1 billion.

There are two basic reasons that the electric vehicle industry in the U.S. has so far opted to plug-in rather than swap out. The first is weight. Batteries are heavy. Every mile of range adds a few pounds to the weigh of an EV battery, so a car with 250 miles of range might be carrying a a pack that weighs as much 1,000 pounds. Replacing a pack of that size is not as simple as swapping out a few D cells from a flashlight. Building a station that can handle these loads, says De Souza, typically costs around $1 million.

Ample tackles the weight problem by breaking the battery pack into pieces. The company uses a modular system of lithium-ion packs, each about the size of shoe box, and arranges them on trays. Each module holds about three kilowatt hours of power and weighs around 30 lb. Most cars take 16 to 32 modules, depending on the size and desired range. The modules are stacked on trays four or five at a time, with a typical car holding three to five trays. The robotic arms in Ample’s stations move the trays one at a time so that they never have to carry more than about 150 pounds. The average swap takes ten minutes. Ample’s goal is to get it down to five minutes by the end of this year.

Each stations holds about ten car’s worth of batteries, all steadily re-charging as cars come and go. This allows them to deliver energy at a rate between 500 kilowatts and 1.5 megawatts per hour with a connection of only 60 to 100 kilowatts. Ample says it can build and deploy one of its swapping stations in a footprint the size of two parking spots for tens of thousands of dollars. No digging is required because power can be taken from an overhang connection. “Give us six weeks. We can set up a whole city,” says Hassounah.

If Ample can deliver on this promise, it would undercut not only the existing swapping options, but most fast chargers as well. According to a BloombergNEF survey last year, installation costs for ultra-fast chargers, which require digging in the ground, ranged from $111,000 to $333,000 per megawatt, with hardware starting at about $30,000 per connector and running as high as $125,000.

While dealing with heavy batteries is a chore, the biggest challenge for swapping is getting automakers to change the way they build EVs. “Compatibility is a massive problem,” says Ryan Fisher, an analyst for electrified transport at BloombergNEF. “When you talk about doing it across multiple manufacturers, that becomes pretty complicated quite quickly.”

Plus, there are other ways of smoothing the peaks and valleys in energy demand that don’t require making alterations to EVs already on the road. The startup Freewire, for instance, stores power in batteries inside of its chargers, allowing them to sip power from the grid and deliver to cars quickly.

When Tesla flirted with swapping, it built a proprietary system with its own swappable packs. Swapping stations in China have largely followed the same model, with carmakers building their own networks. NIO, the industry leader, has done more than 2 million swaps at 192 stations. BloombergNEF analysis shows that NIO’s stations are exceptionally efficient at delivering power, with an average of 1,543 kilowatt hours per day per station—33 times the rate of China’s average public plug-in connectors. But building multiple proprietary swapping networks in the U.S. makes little sense. “It's almost like every car company has to build their own gas stations all around the country,” says De Souza. And creating a standard battery pack for every EV is also a non-starter. Automakers are not about to forfeit control over the most expensive part of an electric vehicle and one of the main ways they differentiate themselves from the competition.

Instead of asking automakers to adapt, Ample has created a flexible system that adapts to automakers.“We've built an adapter plate that has the same shape as the original battery,” says Hassounah. “So for one vehicle, it's a one adapter plate, for another, it's a slightly different plate.”

Each plate is designed to interface with the car in exactly the same way as the original battery, with the same bolts, the same electrical connection, and same software—and meeting the same safety standards. The plate, which holds the battery trays, never leaves the car. “You just put this thing in and it works,” says Hassounah, “kind of like replacing a tire.”

Ample says it is working with five manufacturers and has so far built plates for ten models. Non-disclosure agreements prohibit them from saying which automakers, but models seen in their promotional materials include the Nissan Leaf, Kia Niro and Mercedes-Benz EQC. The idea is for automakers to be able to offer swappable battery packs as an option in their EVs. The biggest hurdle at the moment is getting the car companies, who already struggling with supply chain disruptions, to integrate Ample into their manufacturing. For now, Sally and Ample plan to retrofit Kia Niro’s with swappable battery packs. The hope is that if Sally and other fleet managers say they want to place orders for hundreds of thousands of Ample-ready cars, that will help push manufacturers to build them.

“It's very much in the early stages of the industry,” says Fisher. “So the proof is in the pudding.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

WEC Energy Offered $2.5 Billion US Loan for Renewable Projects

With Trump Looming, Biden’s Green Bank Moves to Close Billions in Deals

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

Climate Tech Funds See Cash Pile Rise to $86 Billion as Investing Slows

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals