Dancers and a Dam: World Bank Hones New Strategy in Mozambique

(Bloomberg) -- World Bank chief Ajay Banga’s visit to Mozambique this month at the invitation of President Daniel Chapo to discuss a $6.4 billion hydropower project the lender is helping fund had all the hallmarks of a political rally.

Dancing women and gyrating men wearing traditional masks were among the hundreds of people who gathered to meet the dignitaries in the central town of Tete, many of them clad in the red garb of the ruling Frelimo party. The six-foot-eight Chapo towered above the crowd as he walked down a red carpet, shaking hands, pumping his fist and shouting chants, with Banga following close behind him. The scene was repeated in Songo, a short helicopter ride away.

While Chapo took full advantage of the events to shore up his own support, Banga said backing for the planned dam is consistent with a new approach he is trying to inculcate at the bank. Its key tenets include cutting red tape to accelerate development in some of the world’s poorest nations.

The shift, which requires the lender’s units to work more closely together to offer everything from funding to political-risk insurance — and focus on bringing in private-sector investment — is already reaping dividends, with project-approval times having almost halved.

Replicating successes across countries “and not reinventing the wheel is all part of what I’m trying to do,” Banga, who has held his post for about two years, said in an interview in Maputo, the capital. “I’m trying to get scale as compared to incremental development.”

That’s a crucial need across much of Africa — and one most nations find hard to fulfill. They include Mozambique, which ranks among the world’s poorest countries, has a median age of about 18 and has massive youth unemployment.

Its problems date back decades. After gaining independence from Portugal in 1975, an event that was itself preceded by a bloody liberation struggle, Mozambique descended into a civil war that dragged on for 17 years.

Debt and corruption scandals have also dogged the nation, as has a Jihadist insurgency in the gas-rich north and a disputed election last year that was followed by protests in which hundreds of people died.

The instability, which has delayed exploitation of some of the biggest gas reserves globally, is a key reason why the World Bank stepped in.

“Working with instability and trying to find a way to help them become stable and developed is what our task is,” said Banga, who previously served as president of Mastercard Inc. and held senior roles at Citigroup Inc. “If a country was stable, they would probably not need us.”

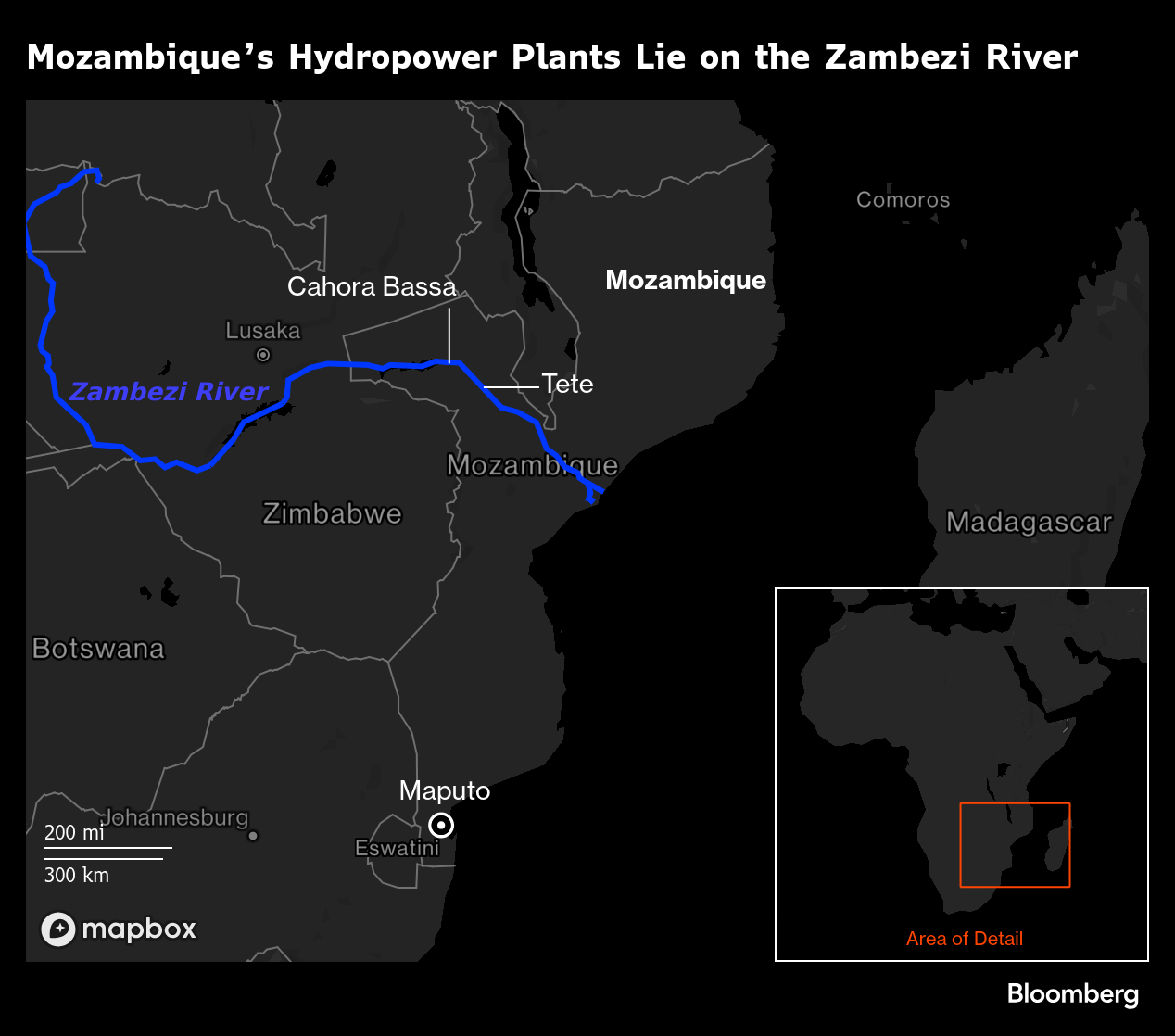

The 1,500-megawatt Mphanda Nkuwa project will be the first major hydropower facility to be built in Mozambique since the 2,075-megawatt Cahora Bassa plant was completed in the dying days of colonial rule in 1974.

A group led by Electricite de France SA, with the International Finance Corp. providing debt and equity, are set to construct the facility about 60 kilometers (37 miles) downstream of Cahora Bassa. Other World Bank arms are funding transmission lines and offering guarantees and insurance to lure private money.

Erik Fernstrom, the World Bank’s infrastructure head for east and southern Africa, pointed out the site from a helicopter on a bend of the muddy Zambezi river, which flows across central Mozambique’s dry, baobab-studded savanna to the Indian Ocean.

The project is expected to support 15,000 jobs during the construction phase and the aim is to use the power it generates to process minerals mined in the country, with any excess exported to neighboring nations.

“You have to play many instruments to make the music work,” Banga told workers and Chapo at Cahora Bassa in reference to the new dam. “It’s not the only thing we will do with Mozambique, but it is probably the single most important one.”

There is some skepticism within Mozambique that the project will deliver the promised benefits and some question the World Bank’s motives and track record.

A Verdade, a prominent independent newspaper, accused Banga of ignoring what it said was Chapo’s “lack of legitimacy” following the disputed election and pointed out that Frelimo has previously blamed the lender for the collapse of the country’s cashew-nut industry and manufacturing sector.

Chapo, who has pledged wide-ranging reforms, reeled off a list of projects he would like to get under way, ranging from new oil pipelines to port expansions and roads. Banga however stressed that World Bank funding for Mozambique — and other countries — is contingent on them changing their regulations to encourage the entry of private capital.

“If it’s necessary to change the law, we will change the law,” Chapo said in an interview. “To create jobs the private sector is the key.”

While posters of Chapo dotted around Maputo herald the onset of “a new era, toward economic independence,” the post-election violence illustrated the disillusionment among young Mozambicans with a party that’s ruled since independence and its failure to ignite the economy despite the country holding some of Africa’s richest natural resources.

Marica Calabrese, the head of Eni SpA’s gas projects in northern Mozambique — a $7 billion floating liquefied natural gas platform with another expected to follow — is upbeat about the nation’s prospects.

“The moment more projects will arrive, there will be even more benefits for Mozambique,” she said. “The potential is definitely huge.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.