Texas Utility Makes Case Pipelines Set ‘Unconscionable’ Prices

(Bloomberg) -- Operations and marketing teams for a Texas pipeline company coordinated to sell gas at ever higher prices during a deadly winter storm in 2021, attorneys for the nation’s largest municipally owned electric and gas utility argued in a San Antonio courtroom. Another pipeline firm commanded an unusually large trading position during the deep freeze that drove up index prices used by the broader market, lawyers for CPS Energy said.

In the three years since Winter Storm Uri claimed at least 246 lives across 77 Texas counties, CPS Energy has refused to pay around $350 million of outstanding bills to units of the two pipeline companies — Energy Transfer LP and Enterprise Products Partners LP — while claiming they unfairly inflated prices during the statewide energy crisis. Last week during a consolidated hearing over the various contract disputes, the utility began to sketch out its case.

The pipelines have asked a judge to toss the utility’s claims in one fell swoop without trials, arguing it failed to properly prepare for the storm then breached its contracts by accepting natural gas with no intention of paying for it. The pipelines have said that behavior by CPS amounts to fraud.

“CPS just didn’t want to pay for it after the fact,” an attorney for Energy Transfer, Bryce Callahan from Yetter Coleman LLP, said at the hearing.

Much of the evidence and expert testimony hasn’t been made public. Still, the arguments made in the recent summary judgment hearing provide a rare look into efforts to challenge the power of big gas suppliers in a state that prefers limited regulation. The 2021 storm that racked up billions in damages spurred calls for change — but little immediate action.

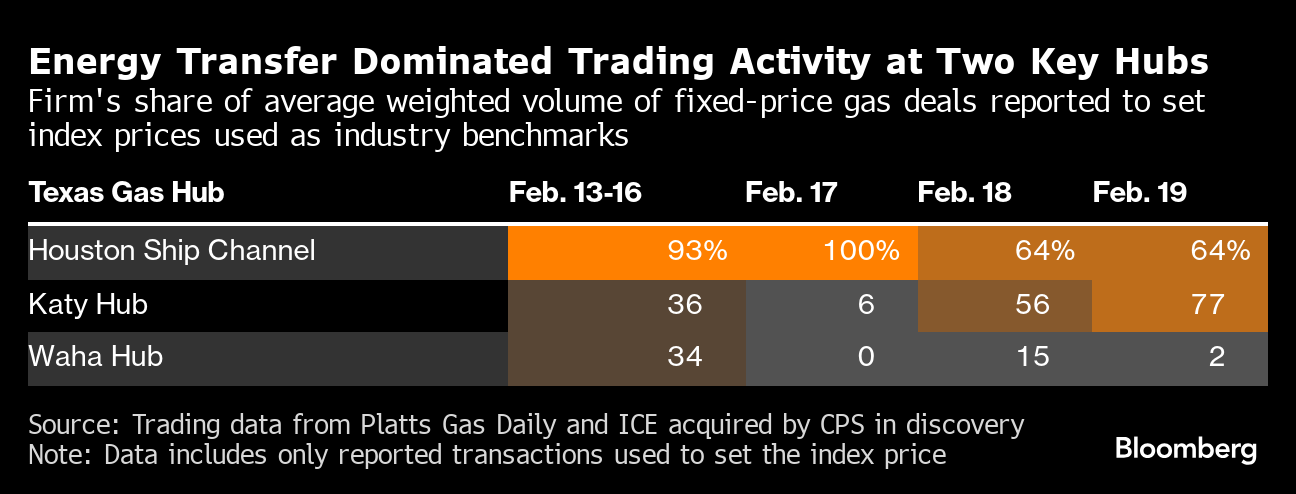

According to San Antonio-based CPS, Energy Transfer’s influence on gas prices during the storm was in part tied to its unusually large trading position at key regional hubs. On Feb. 17, 2021, for instance, Energy Transfer was behind 100% of the gas trades reported at the Houston Ship Channel, according to non-public trading data from the Intercontinental Exchange and Platts Gas Daily shared in the courtroom by CPS. Two days later, when the state was still reeling from frigid conditions, the company was behind more than three-fourths of daily trades reported at the state’s usually quite liquid Katy Hub. Not every company reports its transactions to the index.

The disputed trades between CPS and Energy Transfer were all direct deals done at fixed prices, or prices negotiated directly between the two parties, not at the index prices. But those kinds of fixed-price deals are then used to set the index utilized by the broader market as a pricing benchmark, such as for spot gas purchases or derivatives.

Energy Transfer argues that the overall spot gas market is much bigger than the transitions it reports for the index as many suppliers opt not to report their deals; likewise, its sales to CPS were in line with the market and what CPS negotiated with other suppliers, it says. When index prices went to $359 at the Katy Hub and $208 at Waha on Feb. 17, Energy Transfer accounted for a minority or no trades at those locations.

Separately, CPS said pipeline operator Enterprise — which can monitor metrics like third-party gas flows and storage on its system — used its unique insight into the utility’s growing supply crunch to sell CPS incremental gas at excessive prices. Federal regulations require that firms maintain a strict firewall between their trading arms and interstate pipeline divisions to prevent gaining access to market information others don’t have, but that provision doesn’t apply to Texas intrastate pipelines that don’t leave the state’s borders.

Enterprise’s top executives were also micromanaging deals and urging traders to sell at higher prices even as internal communication shows the pipeline knew CPS was in a vulnerable position, the utility’s counsel said.

In one text exchange presented by CPS, an Enterprise employee said he’d sold gas during the freeze to the utility for $185 per MMBtu, or million British thermal units, a common measure of heating content. That price is well above the $38.83 per MMBtu that CPS claims in court filings “should be declared illegal.” In the Enterprise messages, one executive called the transaction “amazing,” then suggested the original trader “push the numbers.” During normal trading windows, natural gas prices are generally closer to $3 per MMBtu.

The companies said the $38.83 number from CPS is made up and arbitrary. CPS has paid a portion of the bills to the tune of tens of millions of dollars but is contesting the rest, which has been accruing interest.

A transcript of a chat that was introduced at the hearing indicates that CPS was growing increasingly desperate for supply. “I have to buy gas for human need. Please show me offers because I have to buy gas. I have to supply our people,” Ken Skaer, who at the time was manager of gas supply at CPS Energy, said to Enterprise employees during the disaster. That same day, CPS says it was charged more than $400 per MMBtu for gas from Enterprise, priced off the Houston Ship Channel index.

“Profiteering was happening,” said Lauren Valkenaar, a lawyer from Chasnoff Valkenaar & Stribling LLP representing CPS against Enterprise. “Prices were not commercially justifiable.”

The companies have refuted the claims and say CPS breached its contracts, arguing that CPS is a big, sophisticated buyer that knew exactly what it was doing when it agreed to buy gas during the winter storm. CPS could have bought gas ahead of time and stored it, or it could have bought from third parties if it didn’t like the prices, which the pipelines maintain were driven by simple supply and demand fundamentals. The utility could have also bought more financial hedges to mitigate the risk of higher prices. CPS has filed lawsuits to “shift the blame,” Callahan said.

A judge will now decide whether to issue a judgment to halt CPS’s cases against the companies, requiring the utility to pay its outstanding bills. Any claims that remain after that decision will be able to proceed and may take years to resolve. If Enterprise is unsuccessful in getting the claims against it dismissed, they may be heard in front of a jury; Energy Transfer’s would stay in Bexar County and be decided by a judge.

The case is re CPS Energy Gas Supplier Litigation, master file No. 2022-CI-02789, 407th District Court, Bexar County Court, Texas (San Antonio).

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More gas & LNG news

Oman Will Seek Talks With BP, Shell to Secure Latest LNG Project

GE Vernova Sees ‘Humble’ Wind Orders as Data Centers Favor Gas

China’s Oil Demand May Peak Early on Rapid Transport Shift

Qatar Minister Calls Out EU for ESG Overreach, Compliance Costs

Chevron Slows Permian Growth in Hurdle to Trump Oil Plan

After $2.5 Billion IPO Haul, Oman’s OQ Looks at More Share Sales

ADNOC signs 15-year agreement with PETRONAS for Ruwais LNG project

Woodside signs revised EPC deal with Bechtel for Louisiana LNG

Vitol, Glencore Eye New Fortress’ Jamaica LNG Assets