Gas Is Here to Stay for Decades, Say Fossil Fuel Heavyweights

(Bloomberg) -- The biggest fossil fuel players are making the message clear: the transition to a green future will require much more natural gas.

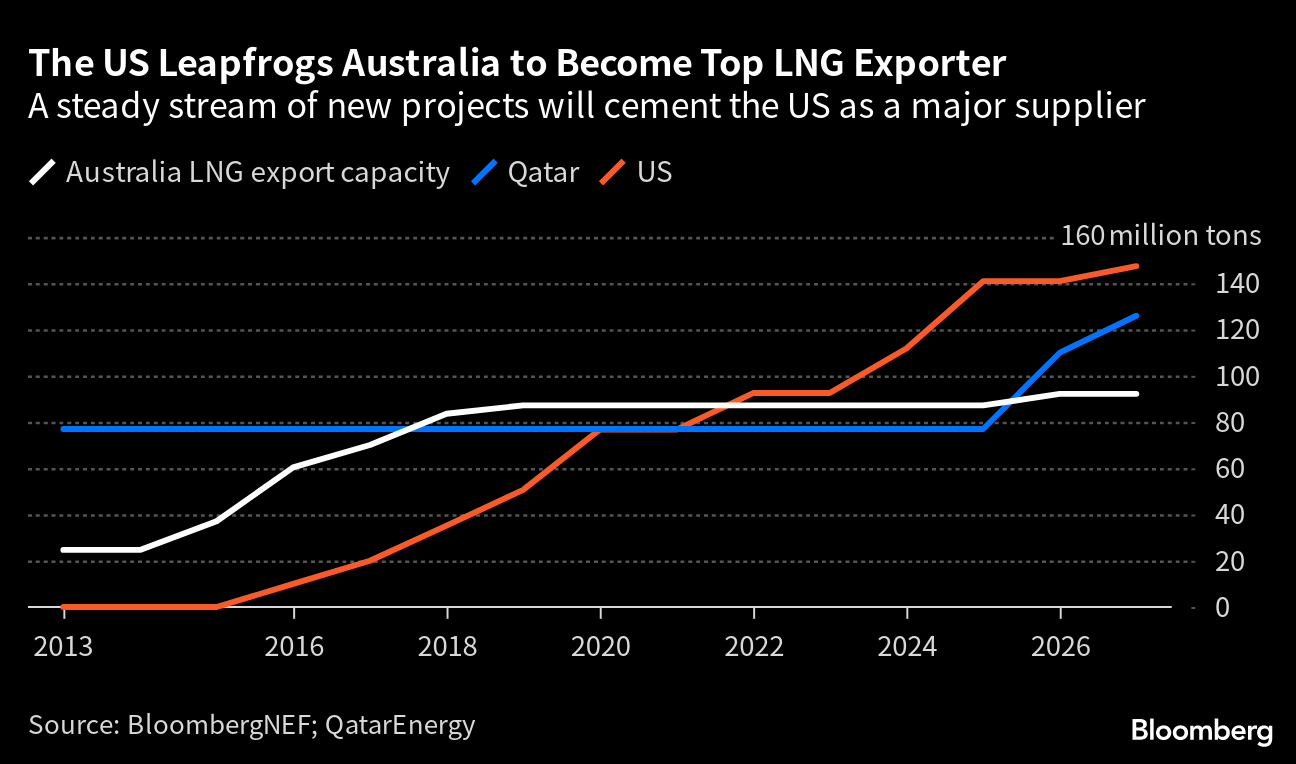

From Shell Plc to Chevron Corp., the world’s top producers plan to accelerate investments in the fuel. China keeps signing deals to buy liquefied natural gas past 2050, with European importers not far behind. The US is forging ahead with new projects that will make it the world’s top LNG exporter for the foreseeable future.

This momentum marks a turning point for gas. The “cleanest” fossil fuel was seen as a short-term bridge to greener energy sources, and environmentalists have sought to phase it out amid worries that gas is far dirtier than advertised. Now, the idea that gas demand will peak anytime soon is disappearing.

“LNG sellers look around this market and feel pretty confident that gas demand will be with us for decades to come,” said Ben Cahill, senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the subsequent energy crisis and record-breaking price surge, has changed the long-term prospects for natural gas. Europe is rushing to replace Russian fuel while emerging nations are signing long-term deals to avoid future shortages.

China signed a 27-year agreement with Qatar on Tuesday to safeguard its energy security, and a German importer on Thursday inked a landmark contract to buy LNG from the US through 2046 — even though Germany aims to be carbon neutral a year before that.

About 60 billion cubic meters of new gas production capacity has been approved since Russia invaded Ukraine, nearly double the rate compared with the past decade, according to the International Energy Agency.

Doubling down on gas also makes sense for shareholders, said Saul Kavonic, a Sydney-based energy analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG. The fuel has been profitable over the last few years while the pursuit of green energy targets has been more of a struggle, he said.

Gas has been the main earnings driver for energy companies including Shell and BP Plc over the past few years. Producers had plunged into the lower-margin renewable power business years before, but are now rethinking those investments due to lackluster returns.

“Liquefied natural gas will play an even bigger role in the energy system of the future than it plays today,” Shell’s Chief Executive Officer Wael Sawan told investors this month as he outlined a strategy shift following his promotion to the role in January. “LNG can be easily transported to places where it is needed most. And what’s more, on average, natural gas emits about 50% less carbon emissions than coal when used to produce electricity.”

Shell plans to increase natural gas investments by about 25% this year to a record $5 billion and keep spending at that level through 2025. Last year, the London-based company joined Exxon Mobil Corp. and ConocoPhillips to invest in Qatar’s $30 billion LNG expansion, the biggest ever in the industry.

Gas is also key to Italian energy group Eni SpA’s growth plans — that was a big motivation behind Friday’s $4.9 billion deal to buy Neptune Energy Group Ltd. Elsewhere, Romania’s two biggest natural gas producers agreed this week to invest as much as €4 billion ($4.4 billion) in a Black Sea gas project after decades of debate. Chevron and Exxon are adding more staff to build up their gas trading activities in London and Singapore.

In the US, the development of new LNG plants is being underpinned as buyers in countries including Germany and Japan — both of which have ambitious green goals — sign long-term contracts with exporters. TotalEnergies SE gave a boost this month to plans to build a US export terminal, agreeing to buy stakes in the project and its developer. The French company is also in discussions with Saudi Arabia to invest in its massive natural gas project.

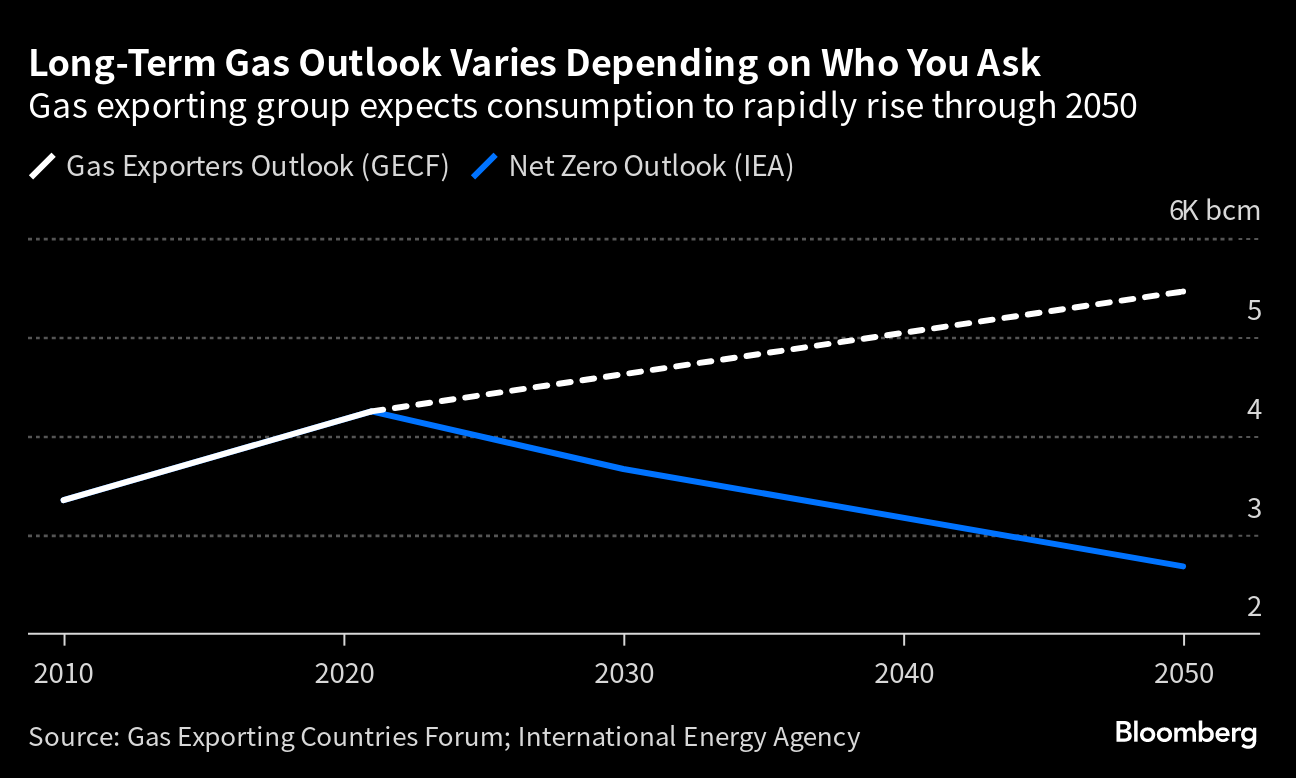

Still, there is a debate over how much gas and investment will be needed, with demand likely to hinge on how successful nations are in reducing emissions.

The IEA says gas demand needs to fall dramatically by the end of the decade in order to keep the world on track for net zero by 2050. The agency in 2021 calculated that all new developments of oil, gas and coal fields need to be stopped to meet that scenario.

Producers and financial institutions need to “commit to end financing and investment in exploration for new oil and gas fields, and expansion of oil and gas reserves,” United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told reporters this month in New York. “We are hurtling towards disaster, eyes wide open.”

One of the biggest arguments against natural gas is methane emissions, a byproduct of gas production that traps more than 80 times more heat than carbon dioxide in its first two decades in the atmosphere. Gas leakage of more than about 3% makes the fuel worse for the climate than coal, according to a study published by the National Academy of Sciences, undermining industry claims that it is a cleaner fossil fuel.

In order to market natural gas as a clean alternative to coal, energy majors are working to cut methane releases. Shell, Exxon Mobil and more than a dozen other producers aim to achieve “near-zero” methane emissions by 2030 as part of an initiative launched last year.

“By finally taking the reduction of methane emissions seriously, the majors believe they can thread the needle of making a positive contribution to climate change and keeping their assets commercially relevant,” said Ira Joseph, a global fellow at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More gas & LNG news

Slovakia Plans Talks on Gas Transit Via Ukraine Starting Next Week

Tesla-Supplier Closure Shows Rising Fallout of Mozambique Unrest

UAE Names Former BP CEO Looney to New Investment Unit Board

Oman Will Seek Talks With BP, Shell to Secure Latest LNG Project

GE Vernova Sees ‘Humble’ Wind Orders as Data Centers Favor Gas

China’s Oil Demand May Peak Early on Rapid Transport Shift

Qatar Minister Calls Out EU for ESG Overreach, Compliance Costs

Chevron Slows Permian Growth in Hurdle to Trump Oil Plan

After $2.5 Billion IPO Haul, Oman’s OQ Looks at More Share Sales