Six Reasons Asia's Oil Refiners Aren't Going Away Anytime Soon

(Bloomberg) -- Predictions of peak oil and the impending demise of fossil fuels will hit Asian oil refiners especially hard. The region is home to three of the top four oil-guzzling nations, and more than a third of global crude processing capacity. Yet, Asian refiners are expanding at a breakneck pace, even building massive new plants designed to run for at least half a century.

What is going on?

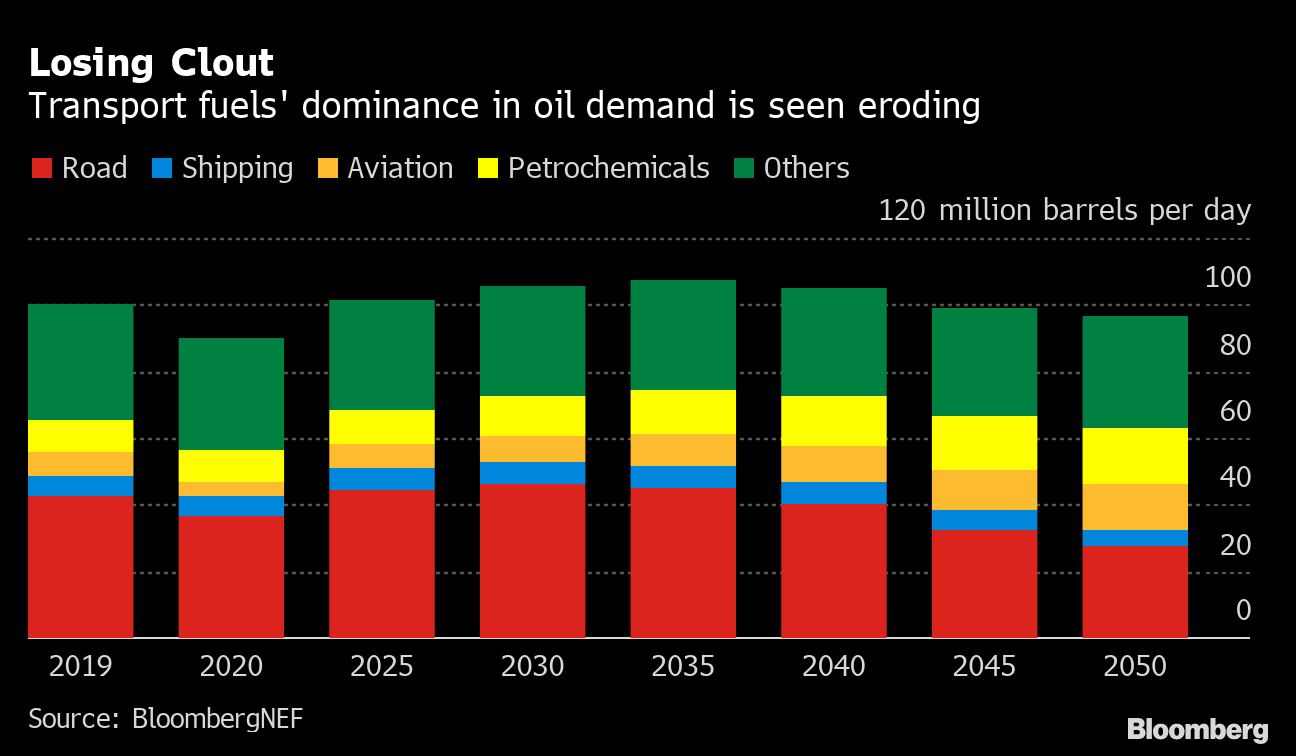

After a century of powering the world’s vehicles, oil refiners are having to plan for an oil-free future in mobility as cars begin switching to batteries, ships burn natural gas, and innovation brings on other energy sources such as hydrogen. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. predicts oil demand for transportation will peak as early as 2026.

Yet, even as a slew of headlines announce oil major BP Plc selling its prized Alaskan fields or Royal Dutch Shell Plc pulling the plug on refineries from Louisiana to the Philippines, Asia’s big refineries are planning for a much longer transition. Chinese refining capacity has nearly tripled since the turn of the millennium, and the nation will end more than a century of U.S. dominance this year. And China’s capacity will continue climbing – to about 20 million barrels a day by 2025, from 17.4 million barrels at the end of 2020. India’s processing is also rising rapidly and could jump by more than half to 8 million barrels a day in the same time.

“Asia is going to be the center of global activity and hence the choices that are being made in Asia about pioneering cleaner technology development, or not, are very important,” said Jeremy Bentham, vice president of global business environment at Royal Dutch Shell Group. “Economic development is going to be very Asian centered, hence the consumption of energy will be very Asian centered and hence then the opportunity to take a lead in deploying clean technologies is there.”

Refiners have begun the long path of reinventing their business. There has been a flurry of announcements from processors in South Korea, China and India in the past few months about ‘net-zero’ targets, switching to hydrogen and capturing carbon. But behind those promises is a business model that will continue to rely for several decades on rising demand for traditional vehicle fuels and even faster growth in the use of petrochemicals and plastics.

“Energy transition is happening in many ways already,” said Sushant Gupta, research director for Asia Pacific refining and oil markets at Wood Mackenzie. “But in Asia, over the next two decades, we still see transport fuel demand. It will be slower, but will still be there.”

Here, then, is a roadmap for Asian oil refiners to make it to 2100 by adapting their businesses in stages.

1. Keep making gasoline

Gasoline and diesel for vehicles may be the first major product area to vanish from refineries, but it is unlikely to happen soon in Asia. About 3.5 million barrels per day of global capacity will be shuttered by the end of 2023 -- 1 million barrels more than has already been announced, industry consultant FGE predicts. But Asia’s big, new refineries have the advantage of modern facilities, located close to growing markets.

Rongsheng Petrochemical Co.’s 800,000 barrels-a- day plant at Zhoushan became fully operational this year and will yield almost 30% transport fuels, mostly gasoline and diesel, and 70% petrochemicals. Hengli Petrochemical began operating its 400,000 barrels-a-day refinery in northeastern China in late 2018, which can produce almost 10 million tons annually of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel.

While Asian refiners produce more vehicle fuel, processors in the mature Western markets are likely to see demand peak sooner as automakers switch to electric propulsion. Already, Shell’s Convent Louisiana facility, three plants of Marathon Petroleum Corp. and two of Phillips 66 are being either shut down or converted into oil terminals or biofuel plants on concern that gasoline demand will never recover from the pandemic-induced slump. Shell announced on Tuesday an agreement to sell its Puget Sound Refinery as it focuses on sites that have integrated oil refineries and chemical plants -- a bet on the future growth of petrochemicals. Almost 80% of US refinery output on average is gasoline or middle distillates – a category that is mostly diesel, according to the IEA.

“There will be closures and there will be the transformation of existing refineries to shift yields from transport fuels to petrochemicals,” Gupta said. Even so, he expects gasoline and diesel yields globally to drop by only 2.5%-3% by 2040.

Some fuel markets will last longer than others. While natural gas and alternatives are becoming increasingly important fuels for big ships, it will take decades to wean the armadas of ferries, fishing vessels and small craft off marine diesel. And jet kerosene will probably remain the only viable propulsion for large aircraft until well into the second half of the century.

2. Produce more plastic

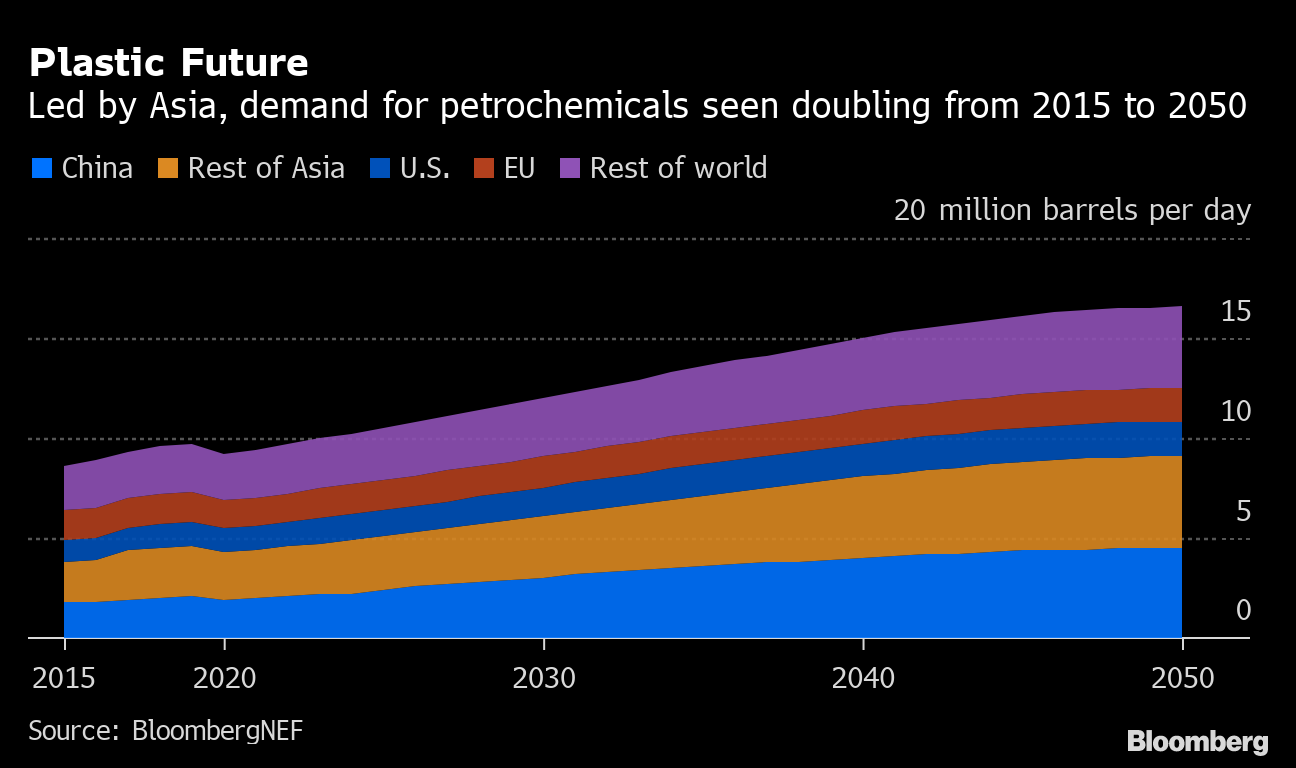

Shifting more capacity to plastics and polymers can be done relatively easily using existing plants. Petrochemicals will account for more than a third of global oil demand growth to 2030 and nearly half through 2050, the International Energy Agency predicts.

Even if the drive to eliminate single-use plastics revives in a post-Covid world, the demand for other petrochemical products, which include everything from water pipes to nail polish, is predicted to keep rising. Asia’s expanding middle class will drive demand for consumer goods and plastics used in buildings and packaging. Ironically, even manufacturers of autos and airplanes will use more plastic as they strive to lighten vehicles to meet emissions standards, according to FGE.

The overall result is that global plastics consumption will rise more than 60% to close to 600 million tons by 2050 from 2019 levels, requiring refiners to produce an additional 7 million barrels a day in feedstock, FGE said.

“Petrochemicals will become the new base-load for oil demand, driven by economic growth and rising consumption especially in emerging markets,” Goldman Sachs said last month.

China, the biggest market, is leading the transition. The country’s new mega refineries can convert as much as half of their crude oil into petrochemicals, way more than the traditional 10%-15% yield for most processors.

In South Korea, home to three of the world’s 10 biggest refining complexes, four new steam crackers will come onstream over the next 4-5 years to make ethylene, the building block for plastics, according to Gupta. India’s Reliance Industries Ltd., which owns the world’s biggest refining complex, plans to replace sales of road fuels like diesel and gasoline, eventually producing only jet fuel and petrochemicals, as part of a plan to reach net zero by 2035. Rival Indian Oil Corp., the nation’s biggest refiner, aims to double petrochemicals output from its nine refineries.

3. Switch to hydrogen

Eventually, markets for traditional transportation fuel will dry up and refiners have already started working on replacements. Perhaps the most promising from the point of view of their traditional business model is hydrogen, which, like gasoline, is a combustible, storable and transportable fuel that could power vehicles of all sizes and types.

“Hydrogen is the ultimate green option,” said to S.S.V. Ramakumar, director for research and development at Indian Oil, which is running a pilot project in New Delhi to power buses using hydrogen spiked with natural gas. “But there is a journey for hydrogen to make to attain that status of mainstream energy source.”

China’s biggest refiner China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., better known as Sinopec, touted the gas in a recent broadcast on state television, and the National Development and Reform Commission, the nation’s top planning body, selected it as one of the nation’s “future industries.” Sinopec has about 27 pilot hydrogen refueling stations and plans to expand the network to around 1,000 by 2025.

“In some cases it will be hydrogen as a gas or liquefied form, and in some cases people are looking at carriers of hydrogen like ammonia, potentially as a fuel for marine,” said Shell’s Bentham.

Refiners are already among the biggest hydrogen producers because they use it to remove sulfur from fuels and to maximize production of gasoline and other lighter fuels. With less gasoline needed, some of that hydrogen can be diverted. But current production of the gas is largely powered using fossil sources, with every kilogram of hydrogen producing about 10 kilograms of CO2, according to Ramakumar.

Like most companies studying hydrogen, Indian Oil is banking on eventually using electricity from wind, solar and hydro power to make carbon-free hydrogen by electrolysis, but it’s also looking at making the fuel from compressed biogas.

Whatever the production method, the cost of making hydrogen needs to drop substantially if it’s to compete commercially with natural gas. That may mean finding places with cheap renewable energy, such as Chile and Saudi Arabia, or relying on improved technology. Under India’s National Hydrogen Energy Mission roadmap, the country could use renewables to make some of the world’s cheapest hydrogen, according to BloombergNEF.

4. Make biofuels

Hydrogen isn’t the only option. An alternative popular in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia that produce palm oil, is to adapt refineries to produce biofuels. “There are limitations to the amount of vegetation and land available for developing those kinds of fuels, but they are there and they will play a role,” said Shell’s Bentham.

Indonesia, the world’s largest palm-oil producer, is planning to produce more biofuels at existing petroleum refineries and also set up dedicated refineries to turn palm oil into biodiesel. It increased the required blend of palm biodiesel to 30% last year. Marathon Petroleum Corp., the largest U.S. refiner, is converting a plant in Dickinson, North Dakota, to make renewable diesel, while Phillips 66’s Rodeo refinery near San Francisco will make fuel from used cooking oil and other fats.

Refiners in Asia and across the globe are also investing in a host of technologies in renewables, energy storage and other alternative fuels. Indian Oil is evaluating prototype batteries based on aluminum-air technology with Israeli startup Phinergy. Trials could take six months to a year and, if successful, would lead eventually to a gigawatt-scale manufacturing facility, Ramakumar said.

5. Capture carbon

Even with the switch to plastics and hydrogen, refineries and the fuels they make will still produce greenhouse gases, so a third part of the plan has to include ways to capture those gases and store or reuse them. The methods to do this have generally been too expensive to be commercial, but rising penalties for CO2 emissions and increased spending on technology are likely to balance the equation.

China’s Sinopec aims to have a 1 million ton carbon capture project running by 2025, while Indian Oil plans to turn carbon monoxide and CO2 into ethanol at its Panipat refinery. To get the technology to work, some companies are teaming up with innovative startups. South Korea’s biggest refiner, SK Innovation Co., has joined a carbon capture and storage research project led by Norway-based Sintec.

6. Get it right

The speedy adoption of technologies such as electric vehicles is causing the biggest shock to the oil industry in half a century and navigating a way through the changes that have already begun won’t be easy. There are likely to be far fewer oil refineries in the second half of the century and the ones that survive will need to adapt rapidly and embrace new markets and new production systems.

“Refiners can no longer ignore these emerging technologies and no longer can they just rely on traditional refining,” WoodMac’s Gupta said. “Non-conventional ways will become more conventional.”

(Adds detail on Shell refinery sale in 11th paragraph.)

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More gas & LNG news

Tesla-Supplier Closure Shows Rising Fallout of Mozambique Unrest

UAE Names Former BP CEO Looney to New Investment Unit Board

Oman Will Seek Talks With BP, Shell to Secure Latest LNG Project

GE Vernova Sees ‘Humble’ Wind Orders as Data Centers Favor Gas

China’s Oil Demand May Peak Early on Rapid Transport Shift

Qatar Minister Calls Out EU for ESG Overreach, Compliance Costs

Chevron Slows Permian Growth in Hurdle to Trump Oil Plan

After $2.5 Billion IPO Haul, Oman’s OQ Looks at More Share Sales

ADNOC signs 15-year agreement with PETRONAS for Ruwais LNG project