A race against time to secure energy supply for the winter

Europe faces a winter in flux. Given continuing uncertainty about the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the proxy economic war on energy, food, and other materials only appears to be escalating. With no immediate end in sight coupled with restricted natural gas flows to Europe; the Continent is bracing for a bleak winter ahead.

Consequently, Europe is in a race to fortify its energy security to protect consumers from power cuts and rationing this winter. Even without an energy supply shock, European governments face the dilemma of protecting households and businesses from exorbitantly high gas and electricity prices or allowing wholesale prices to be passed through to consumers at the cost of higher inflation.

Given the politics of higher energy prices, however, governments may settle on a halfway solution by using a portion of this year’s revenue windfall, from the inflationary effects on tax receipts, to smooth the rise in energy costs on the real economy.

Within Europe, Italy and Germany are the two countries most vulnerable to a gas supply shock, given their heavy use of natural gas and significant dependency on Russia.

In Germany, natural gas provides 26 percent of overall energy requirements, with about 15 percent of electricity generation dependent on natural gas. However, over many years Germany developed an overreliance on a single supplier, and in 2020 almost 60% of its natural gas supply was piped in from Russia largely on long-term contracts. Given the size of the German economy, this represents a significant volume of gas – 55-60 billion cubic meters (and 15.3% of gross available energy).

Italy is even more dependent on gas, which provides slightly over 40% of its total gross energy supply and generates half of its electricity. However, Italy has made more progress than Germany in diversifying its sources of gas, with over three-fifths of its gas now coming from non-Russian sources, principally Algeria. This of course does not shield the Italian economy from the higher cost of gas from non-Russian producers.

Since the Russia-Ukraine conflict began in February 2022, Europe has been on a mission to diversify away from Russian energy. While this has been possible for coal, and shipped oil cargo sanctions will take effect from the end of 2022, natural gas has not yet been subject to EU sanctions. In fact, quite the reverse. Since 2 September, Russia extended the shutdown of gas through key Nord Stream 1 pipeline, citing “malfunctions” on a key turbine along the pipeline. However, the recent restricted flow has been widely seen as a bid to put economic pressure on European governments and undermine EU political support for Ukraine.

Earlier this year, in July, the European Commission coordinated a crisis plan, "Save Gas for a Safe Winter". The central element of this program is a target for member states to reduce gas consumption by 15 percent between Aug. 1, 2022, and March 31, 2023, with provision for it to become mandatory if necessary. Proposed measures include energy savings by lowering heating and air cooling; fuel substitution where feasible; and acceleration of renewables investment.

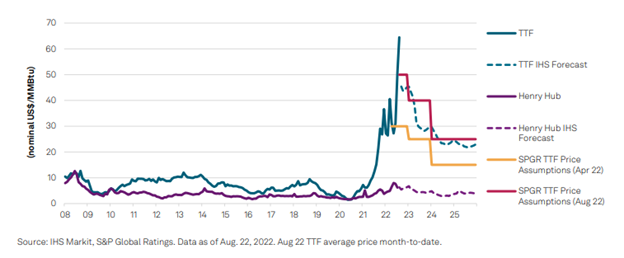

In this downside scenario, we examined the impact of a complete cutoff of the European economy from piped Russian gas. Since the capacity to replace Russian gas with gas imports from other sources is limited, this would restrict supply specifically for winter heating and industrial production. As a result, and as evident already in recent volatility in Title Transfer Facility (TTF) pricing (see chart below), European gas prices would increase significantly above the baseline scenario. Furthermore, some substitutability between fuels would translate into somewhat higher global oil prices.

In addition, in this situation the EU would likely declare a “Union alert” that would enable mandatory gas rationing to be introduced in all member countries, primarily targeting industry (as households and essential services are protected). This would likely be required to achieve the overall 15 percent cut in gas demand compared to the average between August and April over the last five years and over and above the modest scaling back reported so far. S&P Global Commodity Insights reports demand through to the end of July has fallen by about 6% year on year on a weather-adjusted basis across the six largest European economies. These restrictions would affect industries most heavily dependent on gas and all downstream sectors. For example, if restrictions were imposed on manufacturers of glass used in the automotive industry, the reduction in supply (and higher prices) would feed through to car manufacturers, even in the absence of direct restrictions there. Germany would take additional measures.

In particular, according to our assumptions, the country implements the levy on all gas consumers, to pass on 90 percent of the costs currently associated with replacing missing Russian supplies. The levy, together with higher market prices already since the second quarter of 2022, could raise retail gas prices 200 percent year on year on average in the final quarter of this year; retail gas prices would then fall only gradually until end-2025. Retail electricity prices would rise in turn, albeit to a much lesser extent.

Apart from the impact on industrial production, higher gas prices across Europe would lead to a further surge in inflation from the end of the year, reducing households’ real incomes, consumer spending, and, ultimately, GDP growth.

Energy Connects includes information by a variety of sources, such as contributing experts, external journalists and comments from attendees of our events, which may contain personal opinion of others. All opinions expressed are solely the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Energy Connects, dmg events, its parent company DMGT or any affiliates of the same.