Methane emissions remains elusive challenge for oil and gas industry, says WoodMac

Methane remains a significant challenge for the oil and gas industry. COP28 could prove a landmark moment for methane reduction commitments, and companies and governments will need to take strong steps to reduce emissions and enforce new standards, according to a new Horizons report from Wood Mackenzie.

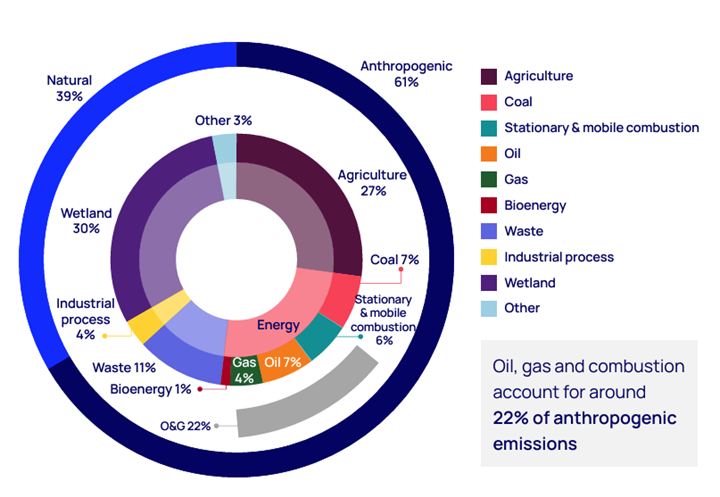

Methane is responsible for almost a third of the emissions-induced increase in global temperatures since the start of the industrial era and the oil and gas industry is estimated to account for up to a quarter of human-caused (anthropogenic) methane emissions, according to the report Mission invisible: tackling the oil and gas industry’s methane challenge.

“The vast majority of methane produced globally is sold as natural gas, but the industry’s challenge lies in its emissions of methane directly into the atmosphere, either intentionally through flaring and venting, or unintentionally through leaks,” said Adam Pollard, principal analyst, upstream emissions for Wood Mackenzie.

Wood Mackenzie classifies emissions in to two broad categories: snowballers, which are minor but innumerable, and super-emitters, which are few by comparison but of very large scale.

“While super-emitters can be reliably tracked by satellite technology, snowballers cannot and they add up to a large cumulative impact,” said Elena Belletti, global head of carbon research for Wood Mackenzie. “So much so, that the currently accepted figure of around 370 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of anthropogenic methane is probably still underestimated.”

According to Wood Mackenzie’s Emissions Benchmarking Tool, typical methane losses per field are small — less than 500 kilogram per hour (around 0.65 million cubic feet per day), which is below the measurable resolution of most current satellites — but around 96% of all fields have emissions on this scale, making it a large, cumulative problem. More significant emissions from larger fields are often spread across multiple production facilities, making them harder to quantify.

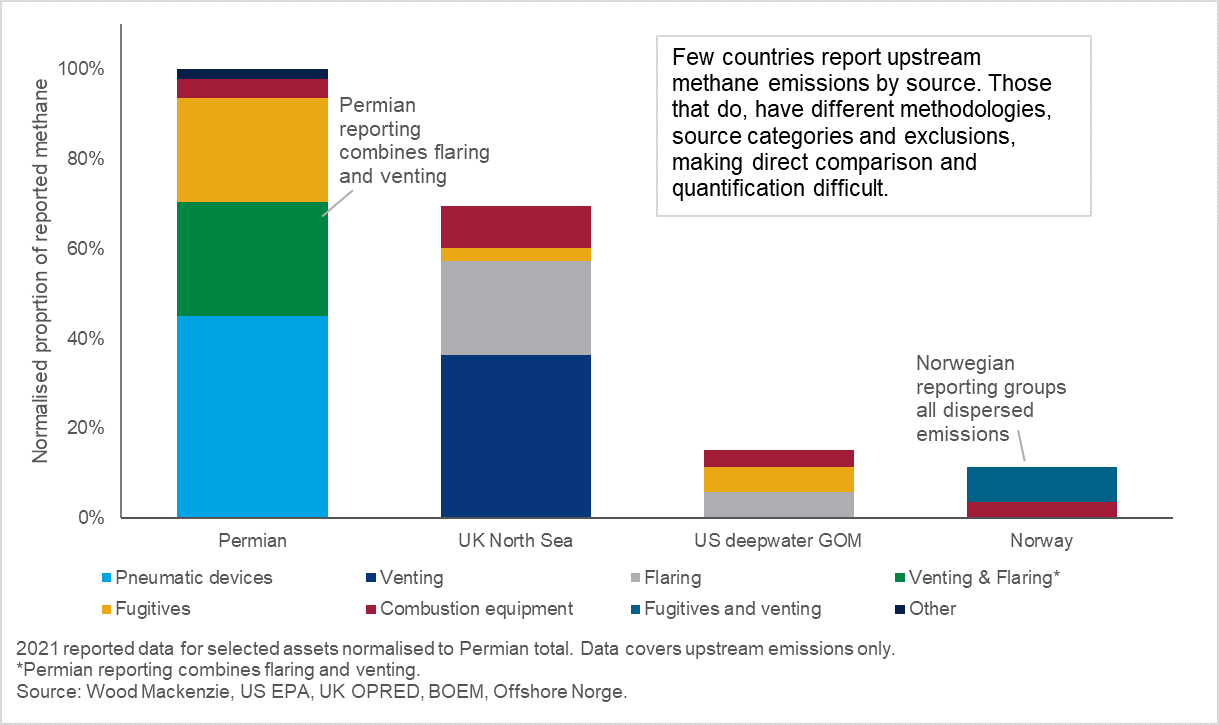

Operational methane emission sources and intensity vary widely by region and asset type

“Tracking methane emissions has been a huge challenge – current satellite technology is not yet able to detect smaller leaks, and airborne or on-the-ground sensors present significant trade-offs on coverage and comparability between different sites,” continued Belletti. “This will come into greater focus as we expect methane reduction commitments to gain momentum at this year’s COP28 climate conference. However, even with the lack of a silver bullet technology to track emissions, there still are existing technologies that can address both the large scale and small-scale leaks. Companies also have financial incentives, as reduced methane losses can increase gas sales and reduce penalties for venting and flaring – which are likely to scale up.”

Oil and gas companies' approach – monetisation

Methane reduction remains one the most achievable ways for oil and gas companies to reduce their scope 1 and 2 emissions – and action is underway. Precedent has been set with the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative’s (OGCI) Aiming for Zero Methane Emissions, the effort of twelve major oil and gas companies to achieve near-zero operated methane emissions by 2030. OGCI member companies have already reduced upstream methane intensity by nearly 45% in the past five years.

“Getting captured emissions into the sales stream should be a main focus for companies, however, the cost to address methane leaks is sometimes greater than the revenue loss, leaving little incentive to act,” said Pollard. “This may change as tougher regulation is put in place, but methane reduction as a service could be a real driver. For example, a methodology was recently passed to generate offsets from plugging methane leaks. The price of these offsets remains relatively low, but as tougher regulations come into play, this kind of offset will become more valuable.”

Pollard also said that companies need to be more regimented in using existing solutions, as reducing flaring and venting often does not require new technology and is straightforward. “For routine operational emissions, progress can easily be made by better monitoring for leaks, tightening valves and swapping out high-bleed devices,” said Pollard.

Source: Wood Mackenzie, based on a range of numbers reported by international organisations (including EPA, EDGAR, CEDS, IIASA, IEA).

Government role

According to the report, government action will be vital to reduction efforts, with three high-level actions that can stimulate progress:

- Greater ambition. Implementable and enforceable policy would be a positive start, such as global collaboration on stopping all large-scale flaring and venting.

- Consistent enforcement. Policymakers and regulators must collaborate with industry to set realistic targets and timelines for emission reductions while ensuring that fees and fines are levied appropriately, and loopholes are closed.

- Financial support for technology. Governments can support funding to improve both measurement technology and abatement solutions. For example, as part of the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) US$350 million in funding is available to monitor and reduce methane emissions.

“Tracking and tackling methane have never been more urgent,” said Belletti. “COP28 could prove to be a watershed for regulating methane emissions if governments move from voluntary pledges to binding commitments. Through tougher penalties and new incentives, companies can transform methane losses into higher revenues and premium prices for certified low-methane supply.”