Sao Paulo Battles Drought and Floods Together in Climate Paradox

(Bloomberg) -- Sao Paulo, one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas housing 21 million people, is living through its largest climate-induced stress test in more than a decade as deadly flash floods collide with a severe drought.

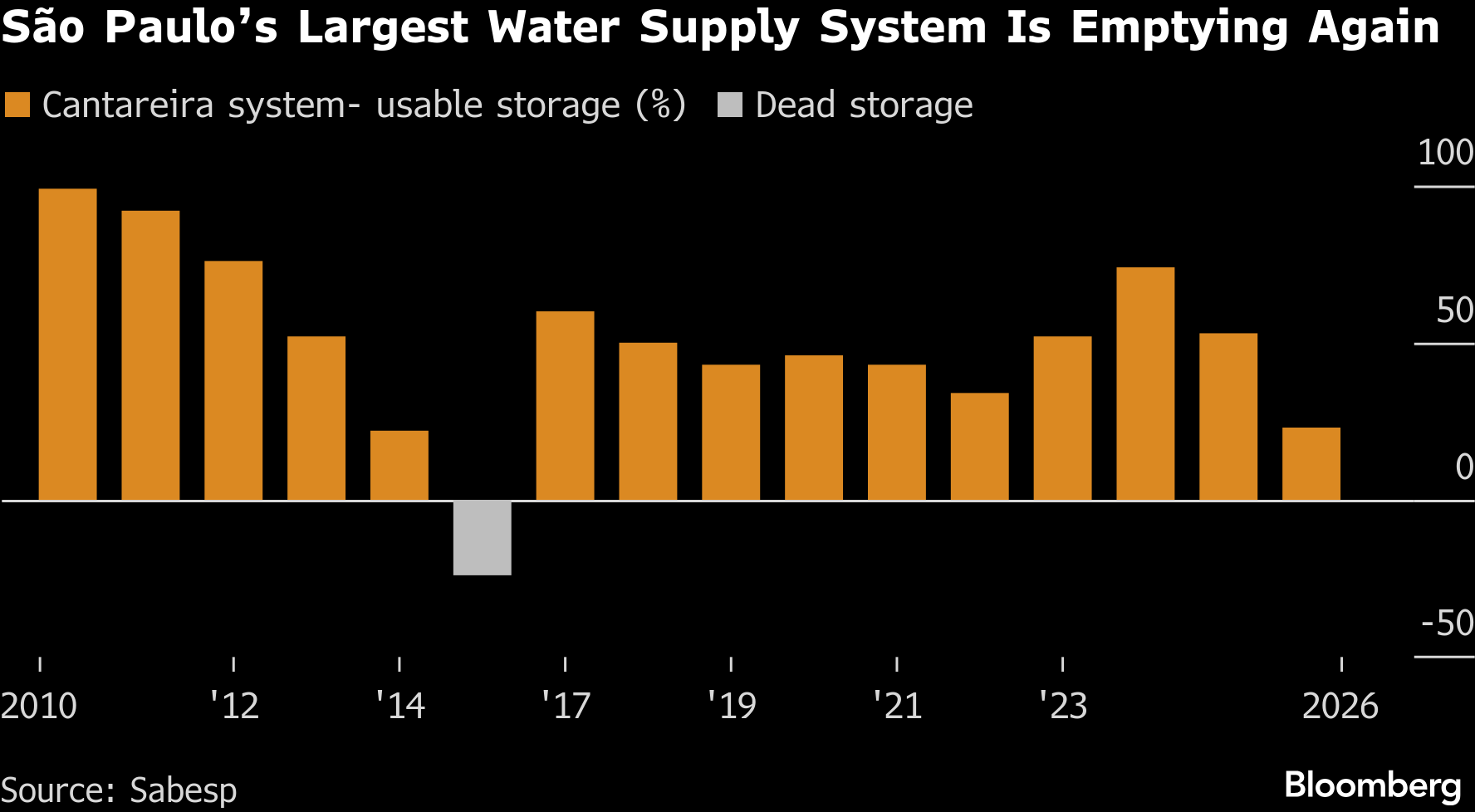

Water in the region’s largest reservoir network is hovering at 32%, the lowest since the region endured its worst water crisis in 2014 and 2015, and is due to dip lower as the dry season approaches. Meanwhile, the Brazilian city has been battered in recent weeks by intense storms that have killed four people, including an elderly couple whose car was swept away by rushing water.

"What's behind all of this is climate change, derived not only from global warming and greenhouse gas emissions, but also from land use change," said Marcelo Seluchi, a meteorologist from Brazil’s National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters, also known as Cemaden.

The federal agency’s data shows that precipitation levels have been falling since the 1960s in much of Brazil, coinciding with widespread deforestation in the central area and in the Amazon. “A forested area evaporates four times more water than pasture,” said Seluchi. “This moisture is a fundamental input for causing rain, along with that which comes from the ocean.”

On the other hand, rising temperatures allow the atmosphere to hold more moisture. That saturated air releases far greater amounts of water in a short time when it rains, producing intense downpours and flash flooding, he said.

The unfolding crisis in Sao Paulo is shaping up to be the city’s largest since a historic drought over a decade ago nearly crippled water supplies for Brazil’s economic engine, home to about 10% of the country’s population

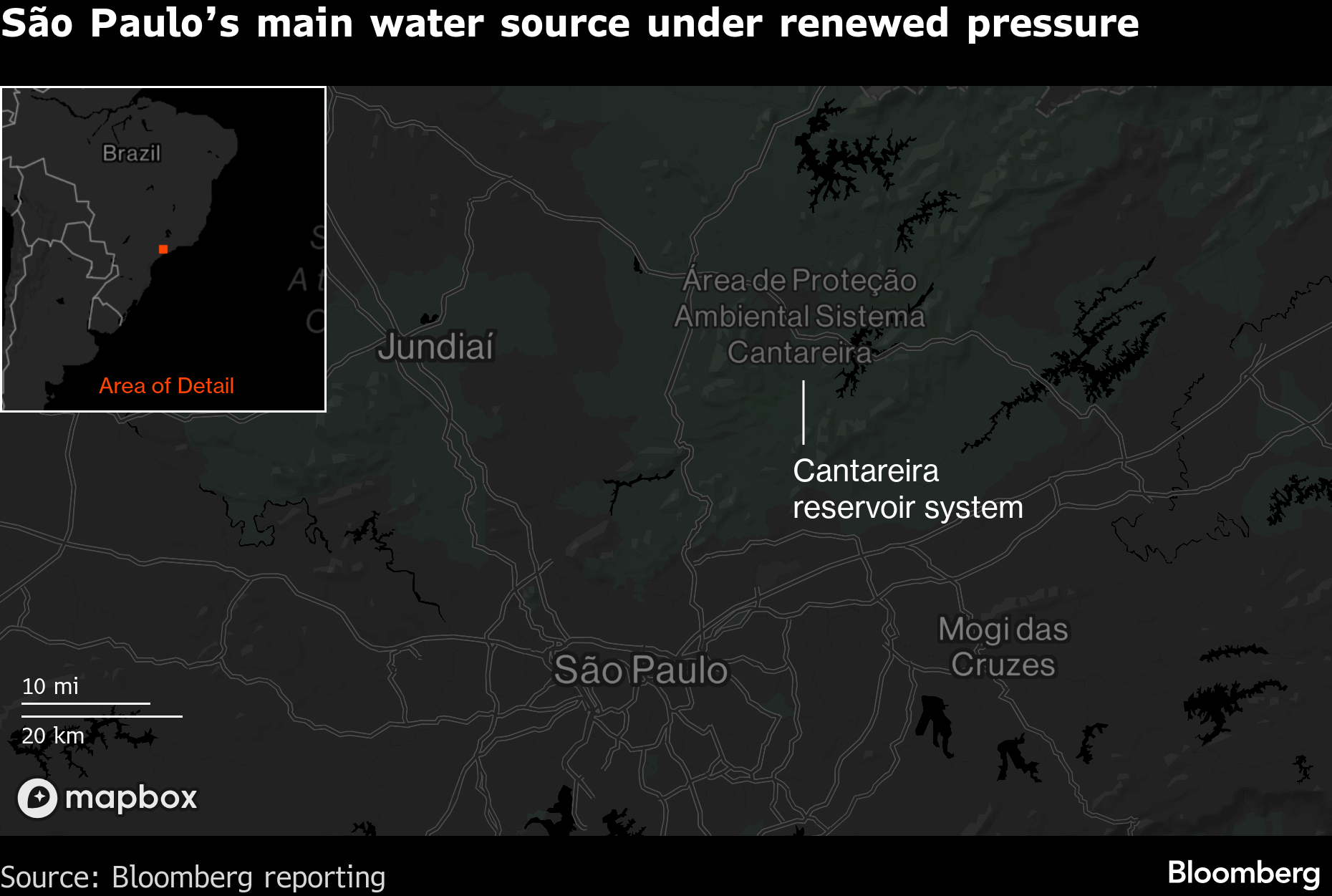

Back then, the Cantareira reservoir system operated under varying restrictions for almost 600 days, impacting millions of people. Several neighborhoods only received water for two to three days a week due to rotating cuts and had to resort to water trucks. Impoverished areas in the outskirts, where water tanks are a luxury, suffered the most.

The crisis affected everything from restaurants to factories, some of which were forced to halt production. Several companies and condominium complexes resorted to drilling their own wells. Drought-related losses totaled $5 billion in 2014 alone, ranking as the world’s fifth-costliest natural catastrophe that year, according to a report by insurer Munich Re.

Now, parts of the city are experiencing similar strains. Pedro Facchini owns a burger shop at the iconic Paulista Avenue, located in one of Sao Paulo’s most affluent neighborhoods. The water cuts off at 10 p.m. every day, but his business continues to operate for another hour and a half. He can’t install a water tank because the restaurant is located inside a gallery.

“In the days I can’t store water to wash the dishes, I have to stop serving and lose revenue,” Facchini said.

Cemaden estimates that the Cantareira system, which supplies water for up to 9 million people, will face restrictions for the rest of the year. If rainfall remains low, Sabesp, Latin America's largest water utility, might have to once again tap so-called dead storage water — sediment-filled pools below the pipes that were used for the first time during the 2014-2015 crisis.

Even when it does rain in Sao Paulo, there’s no guarantee that more water will be collected because the Cantareira system is located quite a distance from the city. Last week, the state government launched a campaign across television, radio and social media urging residents to take shorter showers and repair water leaks. The ad reminded residents that “even when it rains, sometimes not a single drop reaches the reservoirs.”

The metropolis’ paved surfaces present another risk when the clouds finally open up. Over the weekend, heavy rains caused more flash flooding, leaving several streets and avenues impassable and causing a small river to overflow. Thousands of people attending pre-Carnival celebrations had to walk home with their feet in floodwater.

Since August, Sao Paulo’s utilities regulator has instructed Sabesp to reduce nighttime water pressure to limit losses from the system’s extensive underground leaks. The effects are felt most acutely in poorer, outlying neighborhoods and higher-elevation areas, such as Paulista Avenue, where taps often run weak or dry altogether.

Ilana Ori, a student and climate activist who lives in the city’s eastern outskirts, says that she has had to heat up water in the stove and take bucket baths for weeks now. Her house has a water tank, but it isn’t connected to the bathroom.

“The water usually stops flowing around 9:30 p.m., but there have been days with no supply at all,” she said. “Rather than measures that hit the poorest, authorities should support the most vulnerable and curb water use by the most privileged.”

Sabesp said in October that it would install water tanks free of charge in low-income homes that lack proper storage. But Ori said she was unaware of the program and didn't know anyone who had benefited from it.

The utility has invested in several infrastructure projects to alleviate water shortages since the last water crisis, according to Samanta Souza, its director of institutional relations and sustainability. These include a connection to the Paraiba do Sul river basin, which helps replenish the Cantareira, and the creation of the Sao Lourenco system, now the seventh water-supply source serving Sao Paulo.

As a result, more water is available than in the past, Souza said. “It’s as if our glass of water is larger today than it was in 2014,” she said. “We are ready to face a situation like 2014.”

Sabesp, which was privatized in 2024, plans to invest almost $1 billion in improving equipment over the next two years and to speed up reforestation to create a green belt around Cantareira. To tackle the chronic problem of water loss, it’s replacing aging infrastructure and installing 4 million smart meters that allow consumption monitoring every hour via a mobile app to more easily detect leaks.

Sao Paulo state’s public utilities regulator said it is closely monitoring the situation.

Luz Adriana Cuartas, a researcher at Cemaden who has monitored the Cantareira system since the last major drought, argues that a rationing scheme should have been in place since December. The integrated metropolitan system, which gathers all seven sources, is currently operating at about 43% of capacity.

“When conditions become extremely critical, the most responsible course of action is to operate the system as if the worst-case scenario were already in effect,” she said, “precisely to prevent it from happening.”

©2026 Bloomberg L.P.