The World’s Biggest Consumers of Electricity Are Hidden in Plain Sight

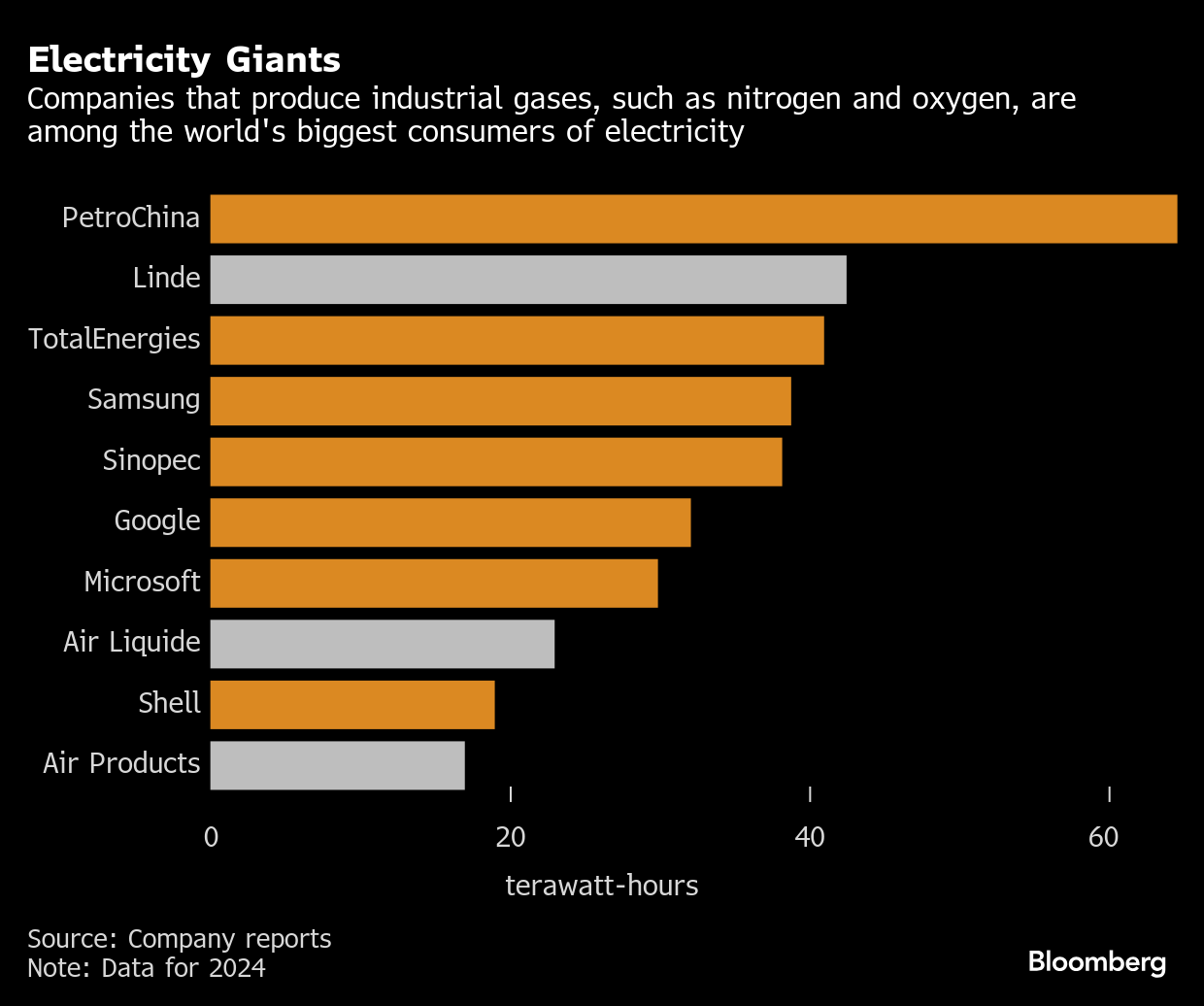

(Bloomberg) -- The rush to secure electricity has intensified as tech companies look to spend trillions of dollars building data centers. There’s an industry that consumes even more power than many tech giants, and it has largely escaped the same scrutiny: suppliers of industrial gases.

Everyday items like toothpaste and life-saving treatments like MRIs are among the countless parts of modern life that hinge on access to gases such as nitrogen, oxygen and helium. Producing and transporting these gases to industrial facilities and hospitals is a highly energy-intensive process.

Three companies — Linde Plc, Air Liquide SA and Air Products and Chemicals Inc. — control 70% of the $120 billion global market for industrial gases. Their initiatives to rein in electricity use or switch to renewables aren’t enough to rapidly cut carbon emissions, according to a new report from the campaign group Action Speaks Louder.

“The scale of the sector’s greenhouse gas emissions and electricity use is staggering,” said George Harding-Rolls, the group’s head of campaigns and one of the authors of the report.

Linde’s electricity use in 2024 exceeded that of Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Samsung Electronics Co. as well as oil giant TotalEnergies SE, while the power use of Air Liquide and Air Products was comparable to that of Shell Plc. and Microsoft Corp. Yet unlike fossil fuel and tech companies, these industrial gas companies are far from household names because their customers are the world’s largest chemicals, steel and oil companies rather than average consumers.

The industry relies on air-separation units, which use giant compressors to turn air into liquid and then distill it into its many components. These machines are responsible for much of the industry’s electricity demand, and their use alone is responsible for 2% of carbon dioxide emissions in China and the US, the world’s two largest polluters.

These companies also produce energy-intensive process gases, such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide and acetylene, which are used for chemical manufacturing and welding.

If only companies’ direct emissions are taken into consideration, then the leading industrial gas firms have impacts comparable to oil majors and retail giants. These so-called Scope 1 and 2 emissions are generated when the company burns fuels on-site or procures electricity from fossil fuel sources.

Linde’s climate and energy goals are the weakest of the three major industrial gas producers, according to Actions Speak Louder. The company has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, but its 2028 target is focused on reducing emissions intensity — a measure of CO2 per unit of electricity consumed. Thus, even if the company’s energy mix gets cleaner, its total emissions may continue to rise.

It can’t do so indefinitely: Linde has committed to an absolute reduction in emissions of 35% by 2035, compared with 2021.

Some industrial customers have “outsourced” the emissions to Linde, said Sanjiv Lamba, the company’s chief executive officer. In other words, instead of making the gases themselves, some companies secure them from Linde instead.

“The fact that we are a large consumer of electricity is in some ways a good thing,” he said. “It gives us the leverage that we need to push to see how renewable energy can become a larger part of the portfolio of energy that we consume.”

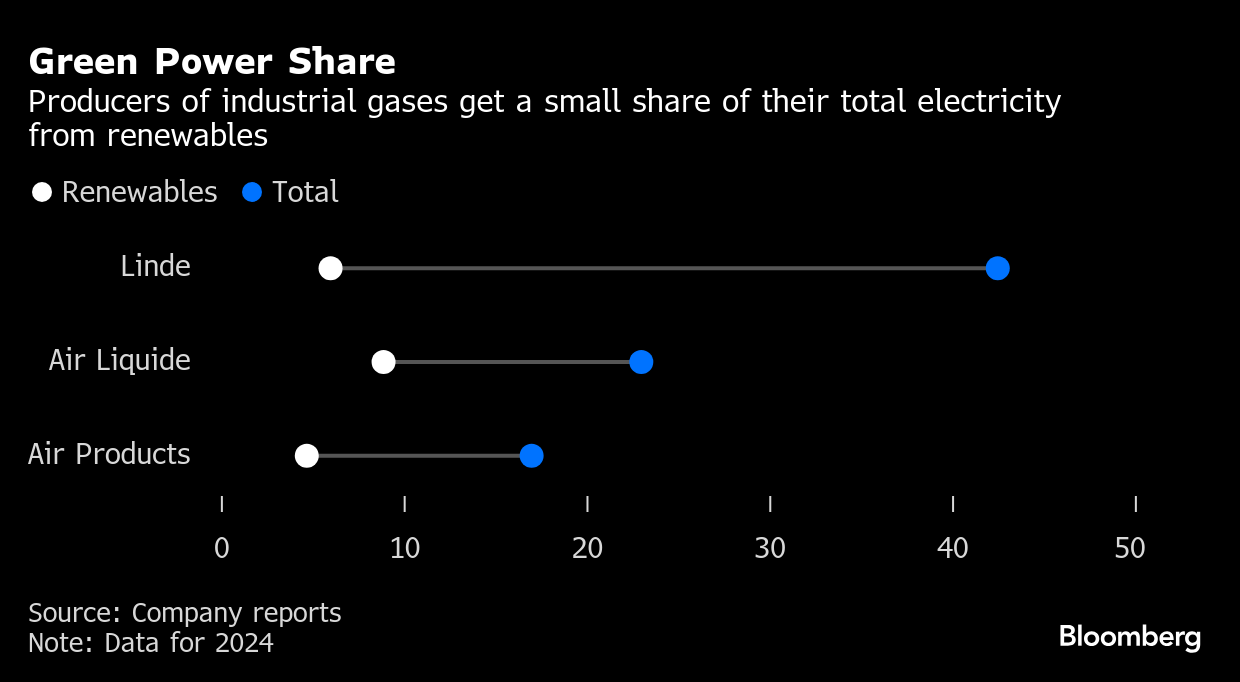

In its 2024 sustainability report, Linde says it secures 47% of its electricity from low-carbon sources. However, only about 14% of its electricity can be reliably sourced back to renewables. The rest of its estimate is based on analyzing the carbon intensity of the grids its operations are connected to and buying renewable energy credits (RECs) or environmental attribute certificates (EACs). Neither leads to emissions reductions, according to experts.

“We have never been fans of credits or attribute certificates,” said Lamba. It’s why Linde has doubled its direct purchase of renewable power in the last four years, he added.

Action Speaks Louder analysis concludes that Linde’s emissions reports use “opaque methodology” that makes it “impossible to verify the full extent of the company’s climate impact.” The company has nearly 600 subsidiaries around the world.

“Our reports have been scrutinized,” said Lamba. “We've gone through audit processes for over 10 to 12 years.”

Air Products has the most ambitious renewable targets among the three major industrial gases companies. It aims to increase the share of renewables in its power mix from 23% in 2023 to more than 90% by 2030. However, the Action Speaks Louder report says that the company’s disclosures are poor. For example, it’s not possible to say how much of Air Products’ renewable electricity is directly sourced and how much comes from RECs or EACs.

“As part of our disclosure strategy, Air Products regularly monitors best practices in the market for disclosure on sustainability-related information,” said Art George, the company’s spokesperson. “We are currently revising our reporting methodology with additional details to come in next year’s report.”

Air Liquide’s goals score a little better than Linde but worse than Air Products, with a commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 alongside a renewable energy goal for 2035. It also says it has electrified more than 90% of its air-separation units, which can lower energy consumption and improve operational efficiency. Non-electric ASUs rely on natural gas or other fuels to generate steam that they use to run their compressors.

However, Harding-Rolls also found that Air Liquide subsidiaries’ emissions and energy-use reporting is strongly lacking in transparency and details. The company also relies heavily on the use of RECs.

“Where markets offer favorable conditions, direct electricity purchase (PPAs) may be complemented with unbundled attributes,” Air Liquide spokesperson said in a statement. “In 2024, unbundled certificates represented only 18% of our total voluntary electricity sourcing.”

The pressure on industrial gases suppliers is growing. Share Action, another green campaign group, published a report in April that concluded these companies “lack robust strategies to transition to renewable energy.” Crucially, with renewables getting cheaper and electricity offering efficiency gains, Share Action argues that these companies are failing to lower their energy cost and thus reducing shareholder returns.

At Linde’s annual general meeting this year, Share Action sent a letter that 22 investors with $2.1 trillion of assets under management signed calling on the company to align its activities with the goals of the Paris Agreement. In 2023, Share Action organized a similar letter for Air Liquide.

Attempts by investors to reduce the emissions of industrial gas companies haven’t always worked. It is why Alix Roy, an analyst with Ecofi and Air Liquide investor, said she has asked the company’s board to respond Ecofi’s concerns about the company’s plans to reduce emissions from energy use.

“We have tried to escalate as much as possible, but so far it has proven inconclusive,” she said.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.