Coal Loophole Undermines Bank Pledges to Cut Fossil Fuel Funding

(Bloomberg) -- In the parts of the financial world that have spent the decade since the Paris Agreement trying to curb the most-polluting fossil fuel, there are actually two distinct types of coal — with two very different sets of rules.

Thermal coal, burned in power plants to generate electricity, faces restrictions from roughly 150 of the world's largest financial companies, according to Paris-based nonprofit Reclaim Finance, which monitors the pledges. Metallurgical coal used to create steel faces pushback from just 13 firms.

Restrictions on thermal coal have been heralded by climate hawks as a crucial lever in breaking the long-running link between finance and fossil fuels, helping to accelerate a transition to cleaner alternatives for producing electricity like solar or wind. The problem is that the distinction between the categories isn’t always so precise and, in some instances, the real-world trade in coal can undermine efforts to isolate the polluting commodity’s use in the energy sector.

A portion of steelmaking coal is suitable for use by power plants, and there can be a switching of cargoes between markets when demand fluctuates or prices are more attractive. While small in volume, the trades have seen a revival in Asia as the steel sector has cooled this year, according to commodities traders in the region, who declined to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly. It follows a spike in the dynamic following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when European utilities clamored for fuel and sent thermal coal prices surging.

Though the scale of the trading is limited, the sales cast doubt on claims by lenders and investors that they can exclude themselves from, or limit their exposure to, coal’s use in the energy industry, while continuing to support the fuel’s deployment in steel mills.

“If prices are low, high-quality coal can indeed also be used for electricity and heat,” said Daan Wentholt, a press officer at Amsterdam-based ING Groep NV, one of the largest lenders to commodities traders and which began exiting thermal coal about a decade ago. The result is the bank “can’t be 100% sure” that it’s in compliance with its own commitment to reduce thermal coal exposure to “close to zero” this year, he said.

Power plants in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have in recent months made purchases of semi-soft coking coal, a type of metallurgical material typically classified as a steelmaking input, according to the traders. Miners, including Whitehaven Coal Ltd. and Peabody Energy Corp., the largest US producer of the fuel, have noted in investor calls this year an industry trend of increased sales in the category to electricity generators.

There “isn’t a 100% distinction between met coal and thermal coal in practice,” said Nazmeera Moola, Cape Town-based chief sustainability officer at Ninety One Plc, which manages about $170 billion of assets and holds shares of Thungela Resources Ltd., a supplier of coal to the energy sector. “So that is a risk that remains.”

Miners and bankers alike have long argued it’s crucial to maintain support for metallurgical coal as few steelmakers have widely available or cheap alternatives to processes that require fossil fuels, and because their products are required for use in everything from power grids to wind turbines.

“Steelmaking coal is recognized as a critical mineral in many countries,” Gary Nagle, chief executive officer of Glencore Plc, one of the world’s largest miners and traders of the commodity, told investors in February. “It’s recognized that this is needed for the transition, so steelmaking coal is in a completely different category to energy coal.”

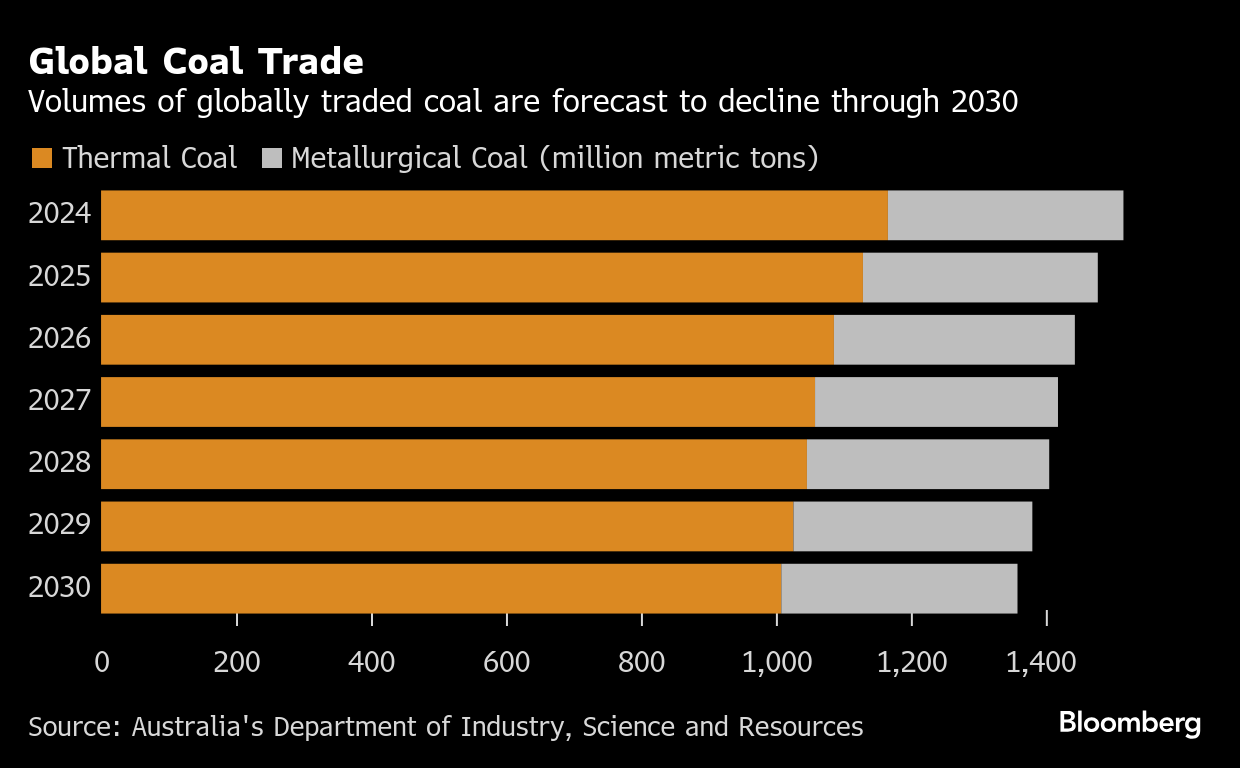

Roughly 1.5 billion tons a year of coal is traded globally — about three-quarters of which is for power plants, according to government estimates in Australia, the top shipper of metallurgical products and second only to Indonesia for thermal categories. Semi-soft coking coal can comprise as much as about 20% of the total metallurgical market, said S&P Global Commodity Insights analyst Paul Bartholomew.

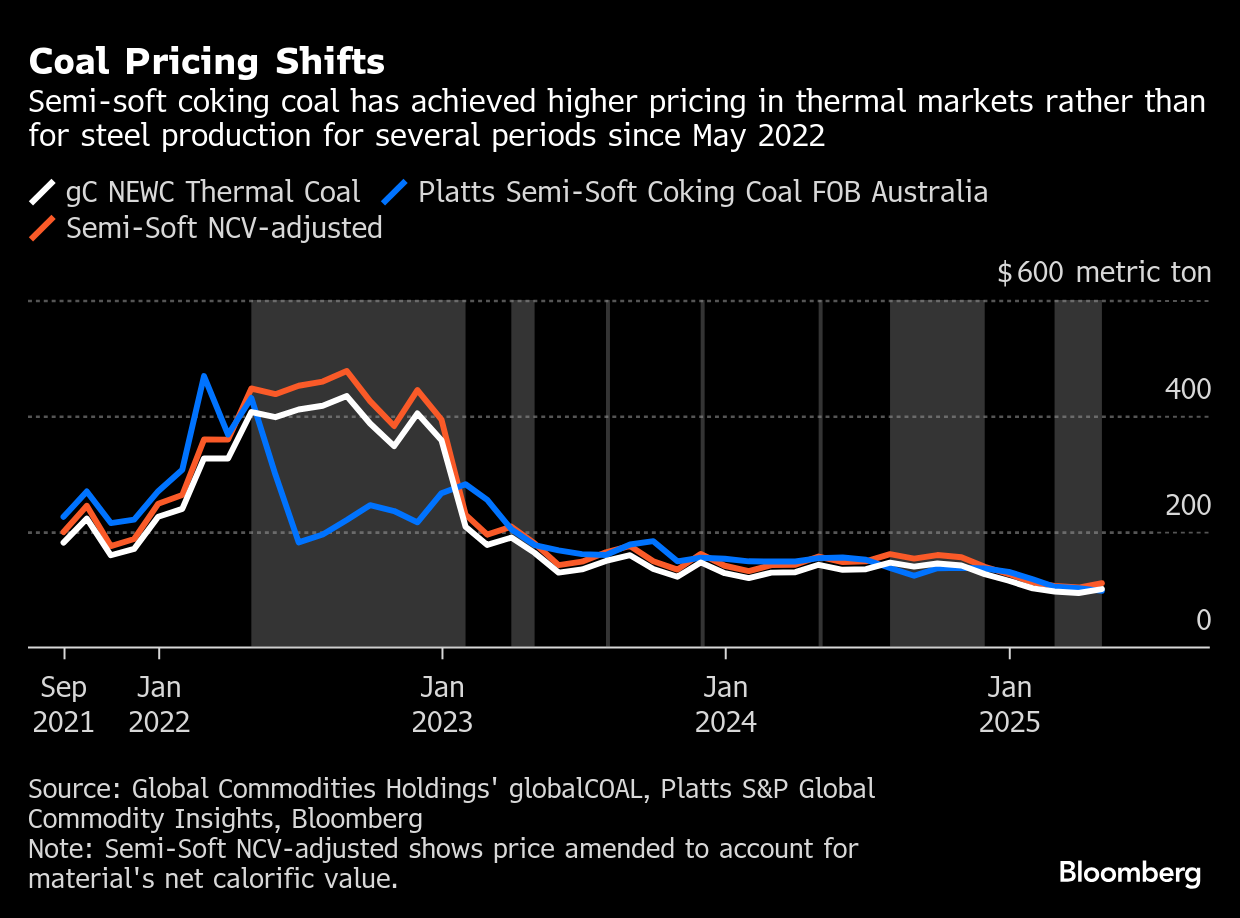

Metallurgical coal has typically commanded a premium over material bound for power stations, though for some types of products those prices have recently been almost identical.

If power-sector coal prices are more lucrative, or if steel demand weakens further, more than a third of Australia’s exports of semi-soft coal could be diverted to thermal markets this year, said Matt Anderson, director of research and consulting at Brisbane-based Commodity Insights Pty. Australia exports about 24 million tons of the material a year, according to the firm’s estimates.

Miners acknowledge they have an ability to switch some products between markets. “This is just an economic question” for specific types of semi-soft material, Whitehaven CEO Paul Flynn said on a February earnings call. Whitehaven declined to comment further.

Ascribing precise definitions to categories of coal doesn’t necessarily reflect a real-world reality that’s “all about shades of gray,” said Nick Stansbury, head of climate solutions at Legal & General and previously head of commodity research.

Since August, the spread between benchmark prices of semi-soft coking and thermal coal has narrowed — and the products have regularly traded within a $10 band per ton, according to data providers globalCOAL and Platts, S&P Global Commodity Insights. Semi-soft rates slipped in May to roughly $3 less than some thermal products.

Because thermal markets factor in the calorific value of coal, prized because it determines the amount of heat released during combustion, sellers have recently been able to achieve a higher price for semi-soft cargoes from power producers than from steelmakers, the traders said.

That’s potentially attractive for miners struggling with squeezed margins. In Queensland, as much as 30% of metallurgical coal production is currently unprofitable, according to Stuart Bocking, CEO of Coal Australia, an industry advocacy body.

Major banks, and in particular US lenders, are already reviewing the restrictions they’ve introduced on fossil fuel projects, and preparing to increase activity in the oil, gas and coal sectors, people familiar with the discussions said in April.

Curbs on coal already can vary widely. Some prevent funding for thermal coal mines, while other policies take a threshold approach and exclude companies that generate more than a certain percentage of revenue from the commodity, or produce more than a specific volume.

Ambiguity over the switching of some metallurgical coal cargoes to power markets can further diminish the impact of the policies, said Yann Louvel, senior financial institutions policy analyst at Reclaim Finance. “Loopholes can make financial institutions' commitments meaningless.”

Since December, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Wall Street peers have led an exodus of global lenders from the United Nations-convened Net-Zero Banking Alliance, which had set voluntary emissions targets for the sector and encouraged greater clean energy financing.

President Donald Trump signed a raft of measures in April aimed at expanding the consumption and production of coal inside the US. That political support may spur financing to the sector, which totaled about $13.9 billion this year through mid-June, compared with $20.4 billion in the same period of 2024, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

China-based firms accounted for more than 80% of loans and bonds issued for coal companies in 2024, and 19 of the 20 largest underwriting entities were all headquartered in the country, the data shows. Outside of China, Bank of America Corp. and Jefferies Financial Group Inc. were the leading providers.

In December 2023, Bank of America replaced a pledge not to finance new thermal coal mines with a requirement for enhanced checks ahead of doing so, as part of a wider walk back of fossil-fuel restrictions. Last year, Sydney-based Macquarie Group Ltd. also loosened its rules to allow for lending or advisory services to, and investments in, metallurgical coal mines, reflecting the “limited viable alternatives” in steelmaking, the bank said in a report published in May.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.