A Software Billionaire Is Betting Big on a Wild Climate Fix

(Bloomberg) -- Moore’s Law says that the number of transistors crammed onto microchips will double every two years, magnifying computing power with a minimum cost increase. It’s been a key benchmark for technological progress since Intel Corporation co-founder Gordon Moore coined the rule in 1965.

The concept is instructive for Mike Cannon-Brookes, the billionaire co-founder of software giant Atlassian Corp. But that’s not the sector where it's most applicable. In his estimation, technology’s most important law applies to the radical transformation of the energy system in the coming decades.

“Moore’s Law is not a law of physics, it’s a law of belief,” the 44-year-old Cannon-Brookes says during a three-hour interview over dinner in Manhattan this past winter. “That belief, though, doesn’t happen with just daydreaming. It happens with really freaking smart people that have been paid a lot of money at Intel and lots of other companies to make that happen. But it starts with, ‘I believe people will need lots more chips in the future and that there will be a market.’”

It’s not a belief that the world will need a lot more renewable power; that’s a given. United Nations reports have laid bare the consequences if we fail to swap fossil fuels for clean energy, from fiercer storms and wildfires to higher seas that swallow coasts.

Where belief comes in for Cannon-Brookes is where the power is generated. If the world's energy grid is a microchip, the Australian billionaire believes his home country is the crucial component, offering the abundant sunshine and land to install millions of solar panels that can increase green electricity generation exponentially. And he’s putting his fortune and technologist mindset to work to will that into existence, including buying a project to link what would be the world’s largest solar farm to Asia via an undersea power line: the SunCable development.

It’s a pivotal moment. At last year’s international climate talks, governments agreed to triple renewable capacity by 2030. There’s no better place to put that principle to work than Australia, which has some of the sunniest land on Earth — but is also the planet’s second-biggest coal exporter. And Cannon-Brookes is treating the problem like a computer scientist would build software.

He’s broken up the project into modular chunks — among them are planning to build a cable factory, map the seabed and submit voluminous amounts of paperwork for siting a massive solar project. He’s also worked on a beta version of a cleaner Australian grid having purchased a major stake in one of the country’s top utilities and getting new board members installed to speed up its decarbonization timeline. None of this is to say his grand vision will come together, let alone be enough to solve the climate crisis. Cannon-Brookes himself has referred to the undersea cable plan as a “completely bats--t insane project,” reflecting the long-shot odds it faces.

“In many facets of the energy transition, we are trying to go bigger or further or faster than we have ever before,” says Dani Alexander, the chief executive officer of the University of New South Wales Energy Institute. “But of course there are technology hurdles that need to be overcome. We see many examples of large infrastructure projects that come up against not just technological hurdles but also regulatory hurdles, political hurdles.”

Atlassian is an enterprise software giant with a global footprint, but while Cannon-Brookes’ efforts to address climate change have made him a household name in Australia, he still has a relatively low profile elsewhere. If his plans to make Australia a renewable energy-exporting powerhouse come true, though, it would make him one of the leading figures in the energy transition.

Cannon-Brookes is a quintessential Gen Xer. Talk to him for more than a few minutes and you’ll hear “dude” quite a few times as well as a not-inconsequential amount of profanity. When he shows up to dinner, he sports a black fleece and his signature long hair pulled back in a ponytail. His climate epiphany also tracks with that of many 40somethings: He saw .

Al Gore’s 2006 slideshow-turned-movie laid out the stark impacts of climate change, many of which have subsequently come to bear faster than anticipated. It affected Cannon-Brookes, though it didn’t exactly change his day-to-day.

“I remember thinking that's a bit f---ed — and then went home and did absolutely nothing,” he says.

To be fair, Cannon-Brookes was pretty busy. He was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1979 but largely grew up in Australia, including going to college at the University of New South Wales.

There, he met Scott Farquhar. The two founded Atlassian, which makes Trello and other project management software, in 2002 following the dot-com bubble. When came out, Atlassian had around 1,000 customers and was continuing to grow. Today, it has over 300,000 customers and generated $3.5 billion in revenue for fiscal year 2023.

Cannon-Brookes says he devotes 95% of his time to the company that’s created the majority of his $11.8 billion fortune , according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. But he has plenty of passion projects to fill that other 5%. He’s a co-owner of the Utah Jazz (he has a multi-decade plan to deliver a championship), and he has a stake in the South Sydney Rabbitohs, the rugby team he grew up rooting for (he’s happy to expound on the long history of the club, named for rabbit meat sellers from the early 20th century).

But get him talking about solar power, and it opens up another realm of obsession. Cannon-Brookes is steeped in the language of renewable energy nerds, waxing on about intracontinental transmission and the duck curve (the graph showing solar power production and energy demand over the course of a day looks like a waterfowl). He talks about demand response patterns and high-voltage direct current with the intensity of relaying the highlights of an NBA Finals game.

“There are a lot of parallel rules about what it takes to have technology disruption: modular technologies, economic change, customer experience,” Cannon-Brookes says of the energy transition. “Everyone changed to a smartphone over a five-year period.”

Averting catastrophic climate change will require a similar rapid societal shift, including changing how energy is generated and delivered. In BloombergNEF’s net-zero scenario, solar will be the world’s largest source of clean energy by 2030. To get there will require building the equivalent of the world’s largest solar farm every few days by the end of the decade.

But traditional project development can be a glacial process. The software development mindset of working in sprints and breaking up tasks into smaller parts could be one way to speed up the timeline.

“One thing Mike did really well was he wasn’t afraid to challenge some of that orthodox thinking,” says Fraser Thompson, one of the three founders of SunCable, the company Cannon-Brookes now owns and that he hopes will create a new paradigm for how renewable energy is generated and transmitted.

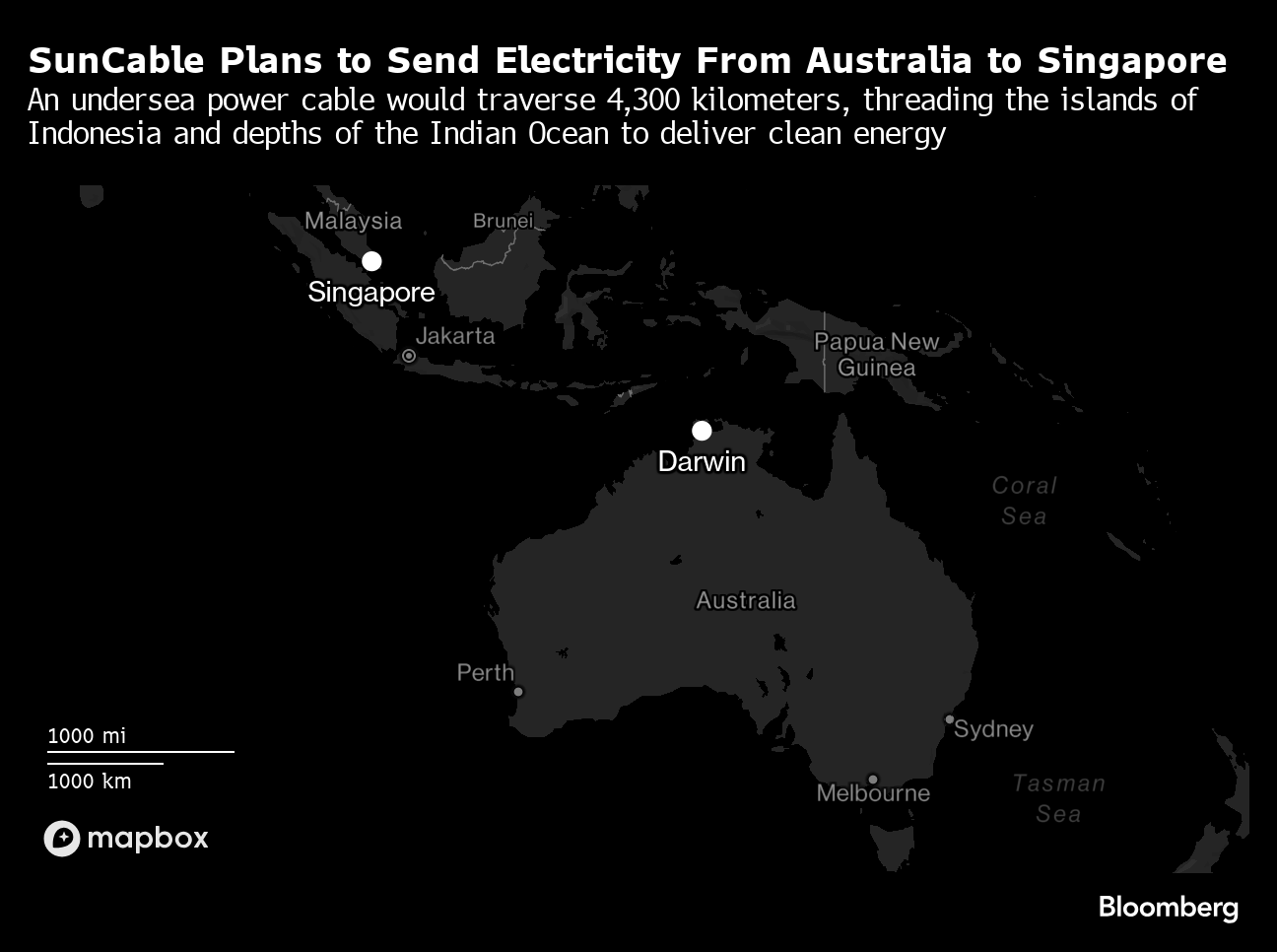

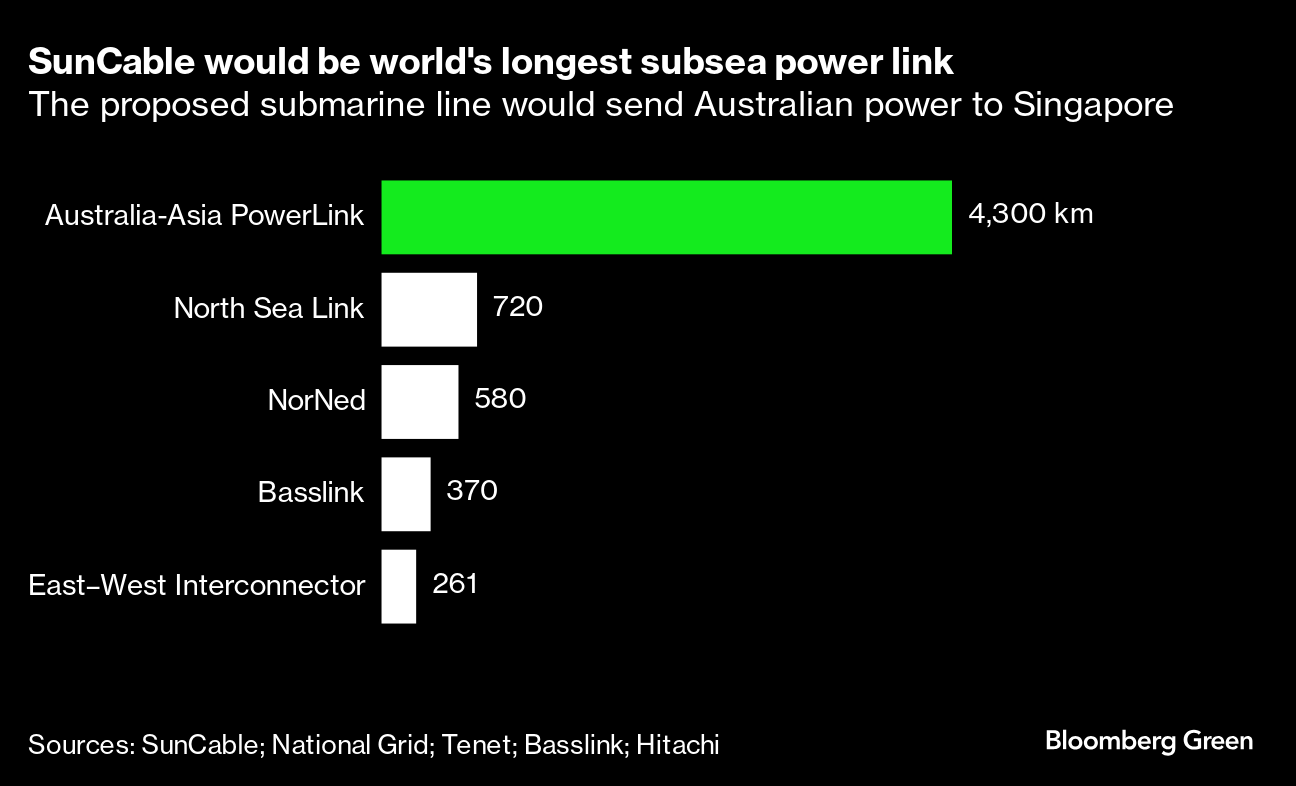

SunCable’s goal is audacious: Build a massive solar farm in Australia and ship the power to Asia via a 4,300-kilometer (2,700-mile) undersea cable. The project is formally known as the Australia-Asia PowerLink and the company was founded in 2018 by a trio of energy and business veterans that include Thompson. Cannon-Brookes had been laying out a vision of Australia’s future for a few years prior to the company’s founding, which led the group to enlist his support.

“Mike was very publicly in the media championing the opportunity for Australia to be at the forefront of the clean energy transition,” at a time when many other public figures “were so blind to this massive economic potential,” says Thompson, who served as chief strategy officer before leaving SunCable last year.

Cannon-Brookes invested in SunCable’s Series A through his investment firm Grok Ventures, as did Andrew Forrest, the billionaire founder of Fortescue Metals Group Ltd., who invested through renewable company Squadron Energy. Both men agreed on solar as the means to generate power for export, which they saw as key to the country’s future. Doing so would take Australia’s long history of exporting natural resources — the biggest source of the country’s wealth — and turn it on its head. For Cannon-Brookes and Forrest, there was no reason one form of energy couldn’t be swapped for another.

Australia’s solar generation potential could easily match the amount of power exported via coal each year. The country could generate 10,000 times more than its total energy consumption solely using the sun, according to government research agency Geoscience Australia. Building enough solar farms to capture even a fraction of that energy and exporting it could slingshot Australia’s economy into the 21st century. (In BNEF’s net-zero scenario, the country will install more than 200 gigawatts of utility-scale and rooftop solar capacity by mid-century.)

SunCable targeted Singapore as a recipient owing to its limited land but voracious appetite for electricity. Its goal is to peak carbon emissions by the end of the decade. That plan is deemed “critically insufficient” by the Climate Action Tracker, which grades countries’ pledges to the Paris Agreement and their plans to meet them. The country also lifted a moratorium on new data centers in 2022 and the industry is slated to grow in tandem with artificial intelligence’s voracious computing needs. That means Singapore has room to increase its ambition — and expand its search for clean power.

The billionaire developers had one key difference of opinion: What, exactly, to export. Forrest favored using solar power to run electrolyzers, machines that split water molecules apart into hydrogen and oxygen. That hydrogen can be used as a clean-burning fuel source, which Forrest wanted to ship abroad via tanker. Cannon-Brookes favored transporting the solar power as electrons via cable.

This difference in opinion proved to be the partnership’s undoing. The tussle over how to run the project eventually led to its collapse; it entered a process called voluntary administration to determine its fate. Cannon-Brookes ultimately emerged as the sole owner.

For Cannon-Brookes, the fight over what to build exemplified two ways of thinking. If someone made a movie about the duo’s dispute over SunCable, he says, “it would be a classic battle between industrialism and technology.” In essence, it would be Willy Wonka versus Iron Man.

Forrest, after all, founded Fortescue, the mining company that’s the world’s fourth-largest iron ore exporter. It’s expected to ship as much as 197 million metric tons of raw steelmaking material in the year ending June 30, and sells the vast majority of its products to China.

“He’s an industrialist, he builds big things. That’s what he’s done,” Cannon-Brookes says. “I’m a technologist, I understand the technology. You look at VC funding of technology companies, it’s very founder-driven and [about] investing in ideas and technology. You look at industrial funding, it’s very different. It's like, ‘hey, I gave you the money, I own the thing’ versus ‘we backed these dudes to do their thing.’”

Many founders have done their thing with great success, from Cannon-Brookes himself to the likes of Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. There are also cautionary tales of successful people and companies who have taken a misstep, from Elon Musk’s ill-fated Hyperloop vision to Apple’s now-shuttered electric vehicle program. Success in one tech field doesn’t necessarily translate to another, particularly building something completely new on a massive scale.

And now, Cannon-Brookes is the guy who owns the thing that requires not one but two major components to work: the largest solar project ever proposed as well as the largest undersea energy transmission cable project.

SunCable plans to build up to 20 gigawatts of solar capacity, an amount equal to all the rooftop solar installed in Australia. There will also be battery backup to store energy once the sun goes down. Then there are the 800 kilometers of overland transmission lines and the high-voltage DC cable capable of transmitting 1.75 gigawatts of the electricity generated along a 4,300-kilometer undersea route to Singapore. Building all this infrastructure is projected to cost A$30 billion ($21 billion), though SunCable wouldn’t share a cost breakdown.

Similar — though far smaller — projects are already operational, including interconnectors between the UK and France, and the NordLink between Germany and Norway that includes more than 500 kilometers of submarine cabling.

Several other ambitious energy generation and subsea transmission projects have been proposed elsewhere. They include a SoftBank-backed group promoting a super grid connecting China, Japan, Mongolia, Russia and South Korea founded in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster, and Xlinks Ltd.’s project that would send Moroccan solar power to the UK. There are also a handful of other projects under various stages of consideration.

That none of the larger developments have been realized so far points to the massive hurdles to constructing the Australia-Asia PowerLink, let alone delivering power to Singapore within the next decade. Seabed mapping has covered around 2,500 kilometers as of March and is still ongoing as are government approvals for the solar farm at the center of the project. But not a single solar panel has been put in the ground nor has a single foot of cable been laid. In fact, not a single foot of cable has been produced.

The Global Wind Energy Council has warned that a lack of cables could be a “critical constraint” for the offshore wind industry, let alone for intercontinental undersea transmission projects. High-voltage DC cable demand in other parts of the world is already straining supply, which is in part why SunCable has elected to manufacture its own. The company identified a “potential site for an advanced cable manufacturing facility” in Tasmania to build a cable manufacturing plant late last year, and is working to secure government financing.

Yet the cable part is the most daunting challenge for the company with “cable” in its name, according to Kavita Surana, a researcher who studies energy transmission and innovation at the Vienna University of Economics and Business. Undersea transmission has largely been limited to sending power generated by offshore wind farms to land over relatively short distances and shallow depths.

“It's a high-risk kind of activity because you need a lot of cable to do it and a depth that has not been proven right now,” Surana says. When asked about the odds of the project succeeding, she takes a palpable pause. “I hope it happens,” she says.

Moreover, there are only a handful of companies in the world with the know-how to manufacture high-voltage underwater cables. While Cannon-Brookes notes that Australia is home to a highly educated workforce, the global knowledge pool to get such a unique cable manufacturing operation off the ground and running without issue is very small. Surana says that it’s “not infeasible” for SunCable to find enough workers to handle such a delicate task, which isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement.

Singapore also has yet to commit to buying energy from SunCable. The nation has granted conditional approvals for an initial 4 gigawatts of clean electricity by 2035 from Cambodia, Indonesia and Vietnam, though it’s continuing talks with other potential suppliers and sees imports accounting for as much as 60% of its power mix in 2050.

Officials have “been in discussion with the companies which have submitted their proposals, including SunCable,” the nation’s Energy Market Authority said in a statement. Singapore will consider factors including “price-competitiveness and source diversity when evaluating the proposals,” the authority said.

Even in the best of scenarios building renewable energy projects, “we often see those unforeseen circumstances coming up and that leading to not just cost blowouts, but also time delays,” says Alexander, the UNSW energy expert.

The project’s costs are already estimated to be well into the billions, but a BNEF analysis shows that several issues, including supply chain problems, have caused “large-scale renewable energy investment in Australia to grind to a halt.” In that environment, a project as costly as the Australia-Asia PowerLink could have trouble finding backers.

“Because it’s so big, the project cost is massive,” says Oliver Senter, founder of Japan Interconnector Inc., a startup developer conducting feasibility studies for high-voltage power lines linking Japan with Taiwan and South Korea. “It gets a bit on the uncomfortable side of project finance.”

The electricity losses as the electrons traverse the sea, impact of ocean currents at depth, complexity of monitoring the system and availability of insurance are all amplified in a larger project, he said.

Projects of 700 kilometers to 1,000 kilometers are “starting to get comfortable, but 3,000 kilometers to 4,000 kilometers is challenging,” according to Senter. “Longer cables over longer areas is more risk for things to go wrong.”

For Surana, it also comes down to the cable figuring out if the “costs outweigh the benefits when you can get the same electricity in Singapore at a lower cost elsewhere or do you need very expensive transmission cable?”

To say Cannon-Brookes’ faith in a Moore’s Law of climate change will be tested by this project would be an understatement. And yet he and the people surrounding him don’t see another option but to keep pushing for Australia’s radical transformation.

“This vision of Australia being a renewable energy superpower and that we are going to deal with climate change?” says Eytan Lenko, a former software executive who runs Cannon-Brookes’ philanthropic effort Boundless. “It is the right vision in the sense that there’s no plan B.”

For Cannon-Brookes, the belief that Plan A has to work has informed more than his work on SunCable. It’s also why he doggedly pursued a plan to take over AGL Australia Ltd., Australia’s largest utility, in 2022 with the intent of speeding up its timeline to end the use of coal. Working with a group including Canadian investment firm Brookfield Corp., Cannon-Brookes submitted a takeover bid that was eventually rejected.

When AGL announced plans to spin its coal plants out — a move that would essentially allow it to claim its generation portfolio was cleaner while the plants continued to operate — Cannon-Brookes took a new tactic: Becoming the company’s largest shareholder and waging a campaign to stop the demerger. He spent around $455 million at the time to buy an 11.3% stake in the utility with a vision of making it a 21st-century clean energy powerhouse.

Cannon-Brookes not only successfully fought the demerger, he also helped flip the board to include four new independent directors.

“Since they’ve done that, it's been beneficial for the company,” says Jamie Hannah, Sydney-based deputy head of investments and capital markets at Van Eck Associates Corp., which holds AGL shares.

Cannon-Brookes’ Grok Ventures has invested around $1 billion, largely in climate startups, to date. He plans to spend $1.5 billion on climate investments and advocacy work, including through his philanthropic fund called Boundless.

The potential market for clean electrons generated on Australian soil is huge. Thompson, one of SunCable’s founders, estimates that should the Asia Pacific region set a target of ensuring 15% of electricity crosses borders, the market could be $490 billion annually.

“Australia, with our abundance of land, our good relationships with our neighbors and the quality of our solar resource, all that means we should be in pole position for that opportunity,” he says.

Cannon-Brookes has a plan to put those pieces together, and a vision of building a network of undersea cables snaking under the Pacific and Indian Oceans to deliver clean power to rapidly developing countries in Asia. But he has to prove it can work once first.

“As I’ve told the company, if we don't get one done, two through 10 don't matter at all,” he said. “We have to focus on one really big and hard problem.”

(Updates to add Singapore Energy Market Authority comment.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.