Sweden’s Once-Pioneering Green Ambitions Are Unravelling

(Bloomberg) -- Six years ago, the cobbled square outside Sweden’s parliament buzzed with energy as Greta Thunberg and her “Fridays for Future” demonstrators urged passing lawmakers to act on climate change through loudhailers and whistles.

On a recent Friday, it was far different. Two protesters, a small cardboard sign and a quiet vigil.

The energy that’s drained out of the campaign mirrors a broader deflation of green ambitions in Sweden and across the continent. Populist groups are pushing back against environmental initiatives, spurred on in part by Donald Trump’s anti-green agenda, and there’s been a weakening of near-term emission-reduction measures, especially where climate and cost-of-living policies have clashed.

The shift is widespread, but it marks a particularly sharp turn for Sweden, long a European leader on climate defense, driving aggressive emissions cuts through fossil fuel taxes and support for cleaner industries.

Now, skepticism has taken hold in parliament, the environmental drive gone into reverse, and investors in giant clean industrial projects are getting cold feet. Among those at risk is the world’s biggest new green steel plant, strapped for cash before it’s even started production.

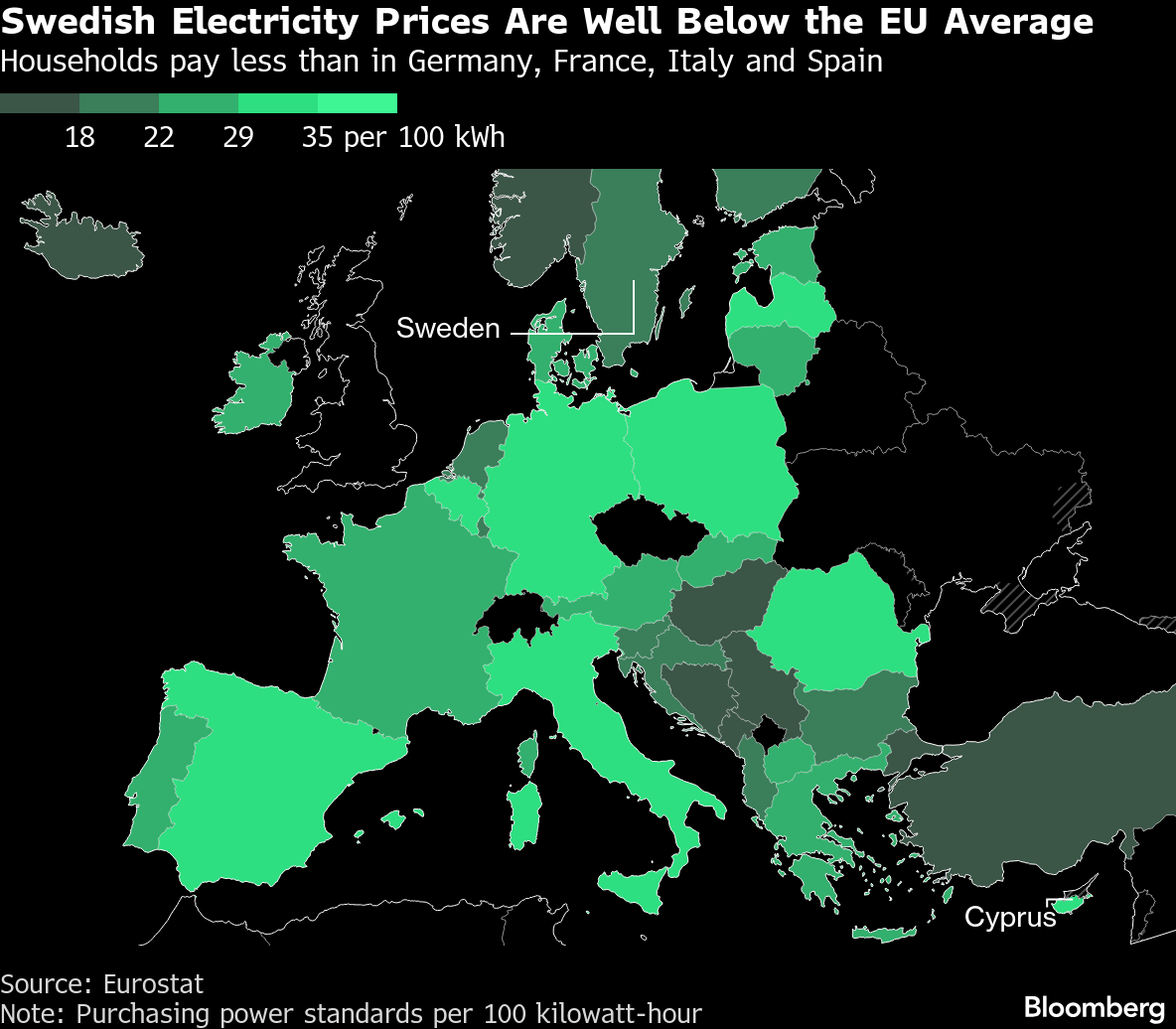

Sweden’s backslide is even more striking given its energy backdrop. The country not only has access to copious amounts of emissions-free electricity from hydro power, nuclear plants and wind farms; More importantly, it’s among the cheapest in the world.

If a rich trailblazer, where consumers have felt the financial benefits of green energy directly in their pockets, can’t stay the course, who can?

“We were one of the first economies in the world that really showed that we could decouple economic development from emissions,” said Johan Rockstrom, a Swedish scientist and director of The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “Now we're losing that reputation of being a country that others respect.”

The most high-profile commercial failure has been Northvolt AB. Once Europe’s best hope for local battery production for car makers and others, cost overruns and production delays pushed it into bankruptcy. After it ran into trouble, the government refused to bail it out.

Stegra AB — the start-up behind the green steel facility — has also received a cold shoulder from fiscal policymakers in Stockholm as it tries to raise capital to avert a funding crisis.

With the next general election just eight months away, battle lines have already emerged around climate issues, and whoever wins will be hugely important to companies with ambitious projects. Opposition parties — including the Social Democrats and Greens — say they will renew the green push through an extension of credit guarantees and grants for emission-lowering industries, as well as a new state green investment bank.

Recent polling suggests the opposition bloc have around a seven-point lead.

Green Revolution

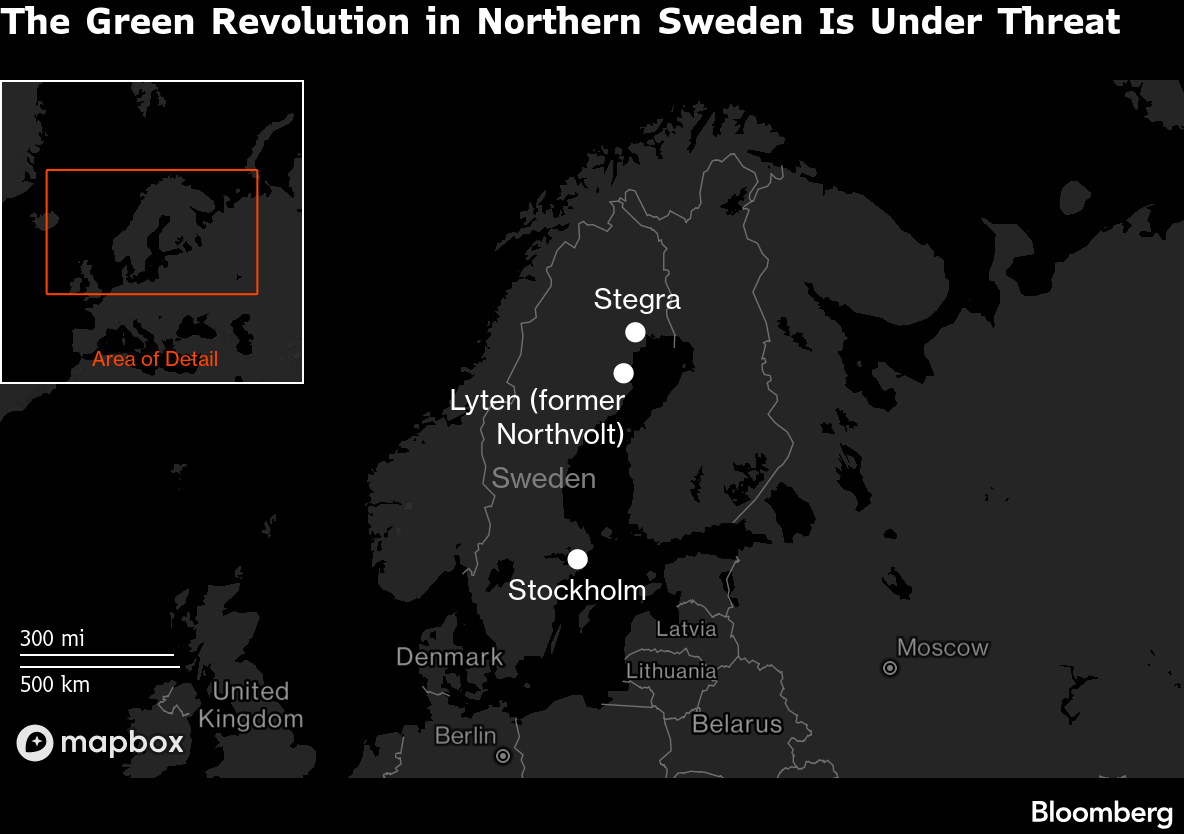

Both Stegra and Northvolt are part of what Sweden’s previous government intended to be a green industrial revolution. The plans are backed by a system of credit guarantees of up to $8.5 billion over the four years to 2025.

The tone changed in 2022, when Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s coalition came to power. It’s supported by the right-wing Sweden Democrats, which believes the climate crisis has been exaggerated.

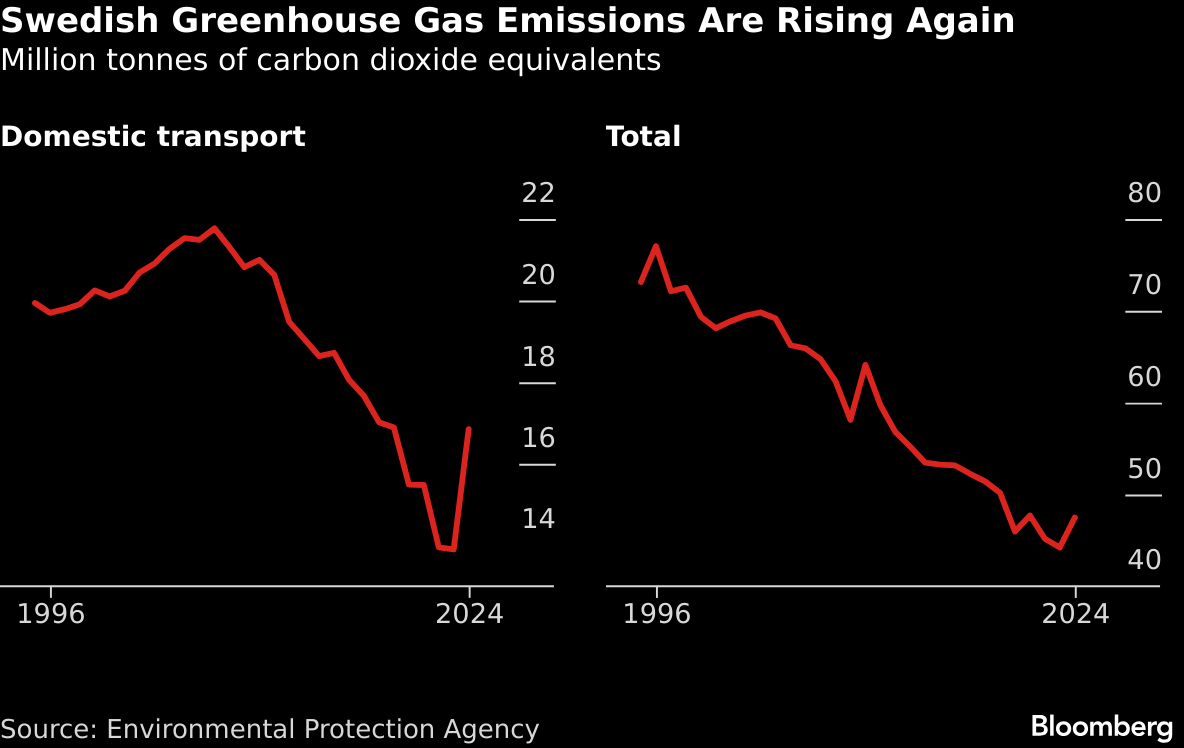

Kristersson made a series of moves that eroded the country’s green credentials, including scrapping the environment ministry, reducing subsidies for electric vehicles, and cutting taxes on diesel to appeal to rural voters unhappy with rising costs. The result? Sweden’s emissions rose 7% in 2024, which the Environmental Protection Agency blamed on higher diesel consumption.

The administration also froze the credit guarantee program and late last year started an inquiry into its effectiveness. It also became more restrictive about grants available under some other programs.

Stegra, for example, recently got 390 million kronor ($43 million) in public money, about a quarter of what it requested. The company is continuing to try to raise funding for its plant.

“At the end of the day, companies have to stand on their own two feet,” Finance Minister Elisabeth Svantesson said in an interview. “The state shouldn't always decide which companies should be supported.”

Meanwhile, other parts of the green revolution have stumbled. A giant fertilizer plant was scrapped because it couldn’t get a power connection, while Danish utility Orsted A/S ended a Swedish green methanol project, saying there wasn’t yet a market.

“For key green transition projects to move forward, you need a positive and long-term vision from the state,” said Daniel Hellden, co-leader of the Green Party.

Some executives, who despite the challenges invest many billions of kronor in Sweden, concur. They want to see political backing.

“The government should take a stronger stand,” said Tobias Hansson, head of the Swedish unit of Hitachi Energy, an electrical infrastructure specialist. “The global management asks why we should invest in Sweden when we can get state aid in Germany, in France, in Canada, in many other countries in the world. This is a dead end from a Swedish perspective.”

Sweden’s hands-off industrial policy and reluctance to put money into individual companies is complicated by the scars of previous decisions, particularly ill-fated efforts to prop up ship building and steel making in the 1970s.

But the current government’s stance is primed to become part of the election campaign. Voters named the environment as one of their top five issues in a recent poll published by newspaper Dagens Nyheter.

The green investments are also intended to benefit some of Sweden’s economically-deprived regions, with large sums targeting the north of the country.

Now, as the plans falter, there’s a clear impact in towns that were supposed to be the heart of a new green economy.

In Skelleftea, the site of the bankrupt Northvolt battery plant, blocks of apartments built for workers now stand empty while businesses in the town have been forced to cut staff.

US battery maker Lyten Inc. bought the site, but is yet to restart operations.

Green infrastructure is capital-intensive and has “strong competition from places like China,” said Keith Norman, chief marketing officer at Lyten. “Consistent government support to get these industries off the ground remains critical.”

In Boden, the site of Stegra’s planned steel mill, the local municipality is up to its neck in debt after building infrastructure and expanding services to be able to accommodate thousands of workers and their families. Stegra’s schedule is now for a 2027 start, several years later than planned. The town of just 28,000 people has 1.56 billion kronor of debt, up from less than 100 million kronor in 2017, and the figure is expected to soar even higher.

Meanwhile, Sweden’s climate targets are drifting out of reach, with the OECD saying it will miss most of its 2030 goals.

On parliament square last month, Christmas shoppers and commuters streamed past the two climate demonstrators, largely oblivious to them.

“We hope a few more people will come,” said one, 24-year-old student Falk Schroter. “We kind of feel a responsibility to keep going, though it’s not our fault everything is getting worse.”

©2026 Bloomberg L.P.