Nuclear Fusion Startup Claims Major Advance in New Zealand Trial

(Bloomberg) -- In New Zealand’s compact capital Wellington, a small group of scientists and engineers just got a little closer to replicating the power of the sun.

OpenStar Technologies on Tuesday successfully floated a half-tonne magnet in a 5-meter-widevacuum chamber of glowing gas heated to more than a million degrees Celsius. A select audience — among them Prime Minister Christopher Luxon and All Blacks great Richie McCaw — looked on from a room above the chamber as the local start-up marked a breakthrough in its bid to achieve sustained nuclear fusion.

While the reactor isn’t yet producing more power than it consumes, which is a large hurdle for fusion reactors, achieving levitation is an early step that proves the design could be viable.

OpenStar Chief Executive Officer and founder Ratu Mataira is betting the simplicity of the company’s reactor design gives it the edge in the global race to turn fusion from theory into an effective power source. For Mataira, levitating the superconductor magnet is proof that the technology behind OpenStar’s first prototype device — called Junior and costing less than $10 million — can work at many times the scale.

“No one yet has a working fusion system that can produce economic electricity,” said the 33-year-old physicist, who ran a paintball business for two years and has a PhD in applied superconductivity. “Starting with a simpler system that we can scale sooner, and make cheaper faster, is attractive.”

OpenStar is a minnow in a competition which has pulled in nearly $10 billion in funding from the likes of Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. About 50 firms around the world are battling to be the first to smash atomic nuclei together to create cheap power at a time when the artificial intelligence boom is fueling demand for electricity and climate change is sparking a hunt for cleaner energy.

The latter part is particularly key for New Zealand, which already generates more than 80% of electricity from renewable energy sources, with hydropower making up more than half of the total.

“Fusion energy has the potential to revolutionize the energy sector by providing a limitless source of safe, clean energy,” said Luxon, who almost missed OpenStar’s feat due to traffic. “After what we have just seen, it is clear this prospect is closer to reality than ever before.”

The timeline to that goal is uncertain, with predictions ranging from 10 to 30 years from now. Other countries have also claimed breakthroughs, such as in 2022 when scientists at a laboratory in California managed for the first time to generate more energy from a fusion reaction than they needed to trigger it. And OpenStar has already outlined that multiple generations of prototypes will be needed before a model capable of generating sufficient energy to power an urban area could, potentially, be built.

But Mataira reckons his firm can be quicker than its rivals, and he can trace the start of his journey to a chance conversation over dinner with a friend who was visiting from Tokyo in 2021.

Nuclear fusion requires plasma — a fourth state of matter (along with solid, liquid and gas) which is so hot that electrons are torn from atoms to create an ionized gas. Stars, lightning and the auroras are forms of plasma.

Heat and gravity pull in plasma within the sun, confining the gas to the center. Immense pressure causes the plasma to fuse, generating energy that powers the solar system.

One way to replicate this process on Earth is by using magnetic fields to confine plasma and make it fuse.

The typical donut-shaped tokamak reactor — first developed by the Soviet Union in the 1950s — has powerful magnets outside a chamber confining plasma. This design is used by the multi-billion-dollar International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project in southern France. The downsides are the cost and the potential instability of the plasma.

In 1987, Japanese theoretical physicist and engineer Akira Hasegawa turned that design on its head — or rather, inside out — with the idea of placing a high-temperature superconducting magnet the plasma rather than around it — a so-called levitated dipole reactor.

In 2004, MIT and Columbia demonstrated its feasibility by successfully confining plasma. But work ended due to a lack of funding and sufficient engineering tools.

Seventeen years later, Mataira was completing his PhD at Victoria University of Wellington’s Robinson Research Institute, working on superconducting magnets, when he met his friend for dinner.

That friend was doing a master’s degree in fusion at the University of Tokyo — where, in a neighboring lab, researchers were experimenting with a levitated dipole reactor.

“I said, ‘What on earth is that?’” Mataira recalled. “And as he described it, I realized every fusion engineer on Earth probably thinks this is insane for engineering reasons.”

To Mataira, it was not.

“Everybody thinks this is impossible,” he said. “But I knew we were sitting on the solutions. We have a new generation of superconducting power supplies that make these machines perfectly reasonable to build. That was the aha moment.”

Mataira spent the following months testing whether the idea was viable. In 2021, he started OpenStar and the following year secured NZ$10 million ($6 million) seed financing to build the company’s first levitated dipole machine: Junior.

On Oct. 31, 2024 the firm confined plasma — the critical step showing the machine could be scaled to produce fusion energy.

For Mataira, their design was much easier to develop and build than the conventional model.

“A tokamak is much more like a jet engine in the way you have to think about it and design it — and in how you extract performance. It benefits enormously from advanced simulations and precision manufacturing,” he said. “A dipole is more like a fire pit. You arrange things roughly, add heat, and once the fire catches it largely takes care of itself. You don’t rely on simulations in the same way to make incremental improvements.”

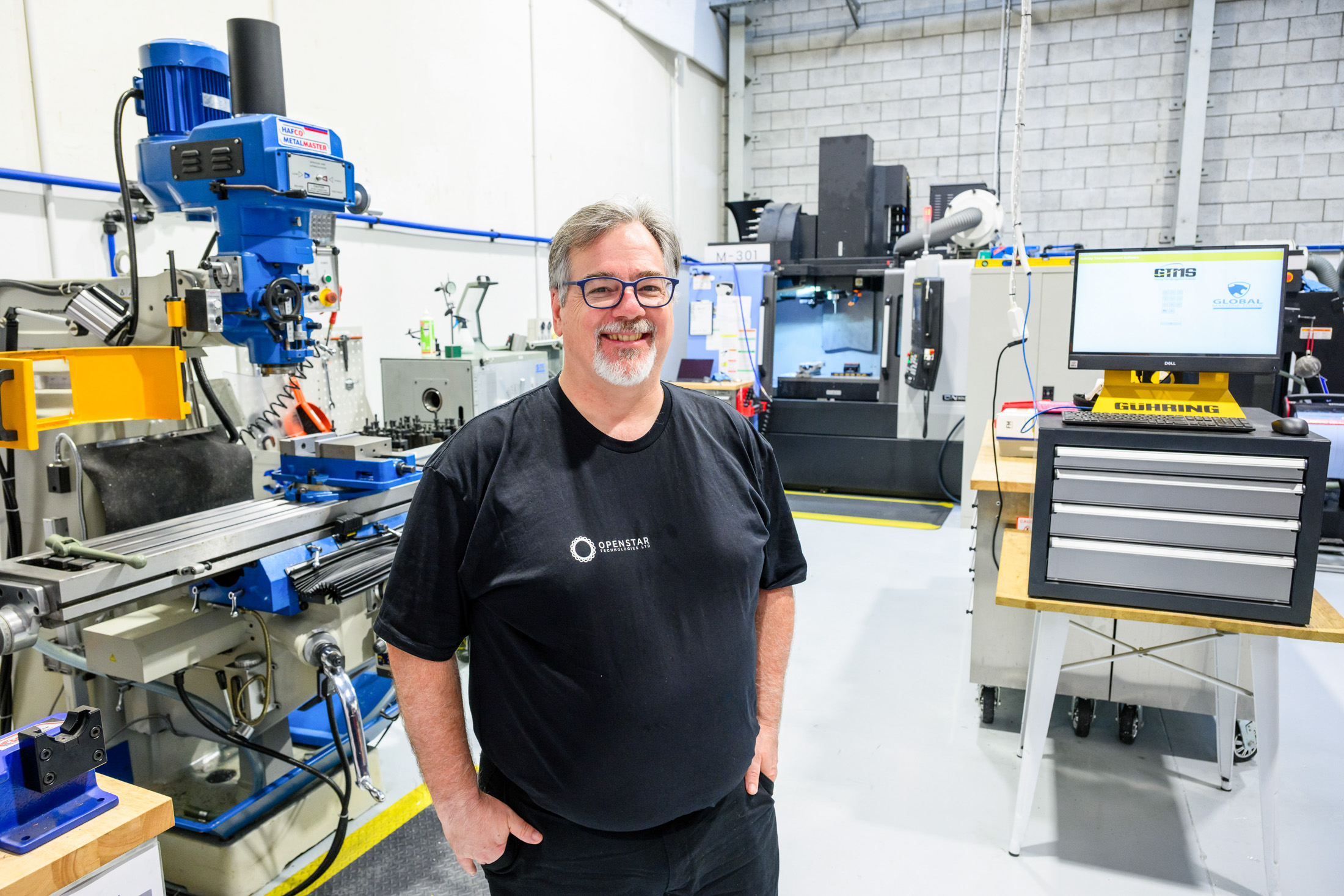

OpenStar now employs around 80 scientists, engineers and support staff, including Darren Garnier, who was one of the leads on the original MIT experiments in the early 2000s and moved to New Zealand to continue his work.

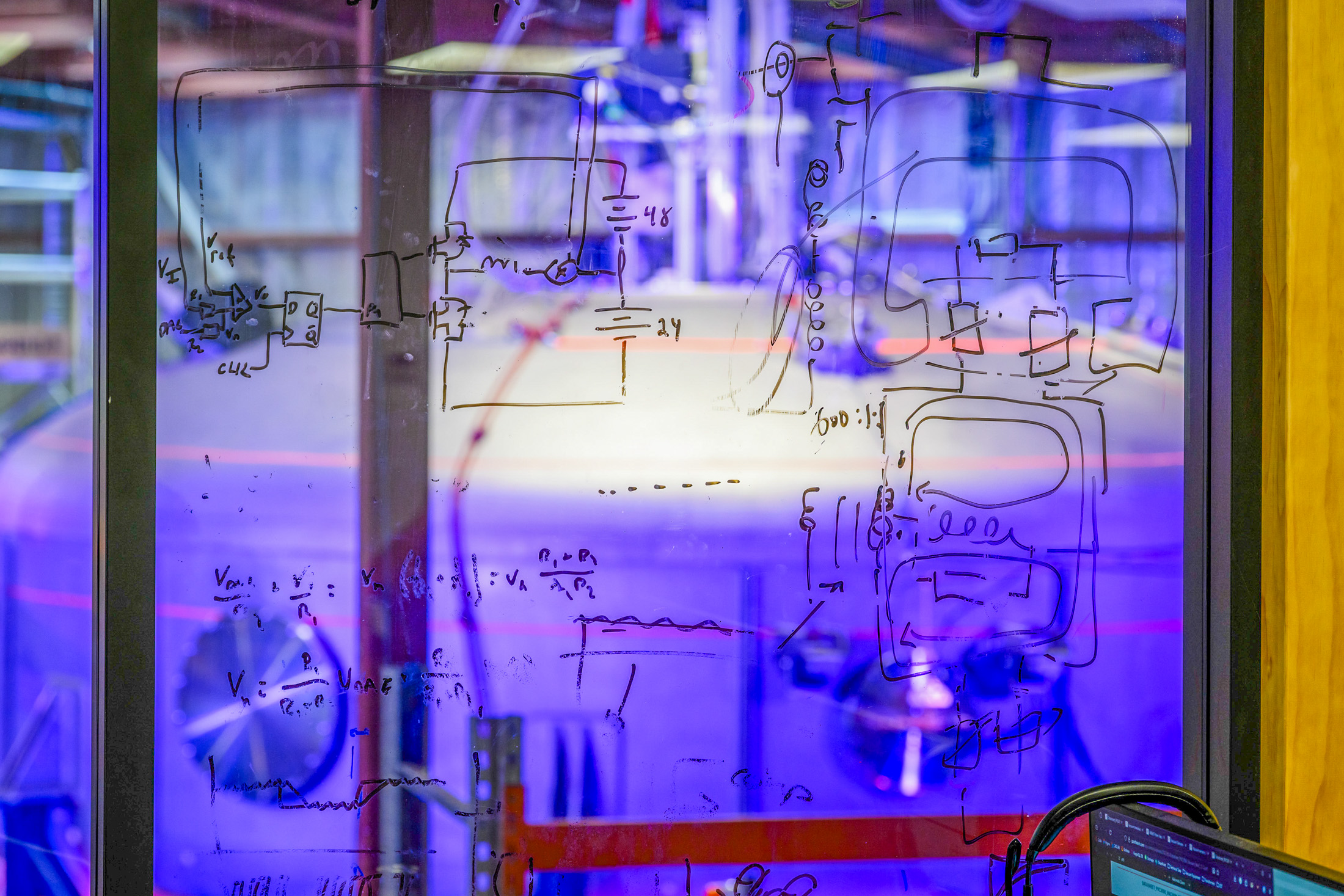

“I’ve been waiting 15 years for this,” Garnier said in a meeting room at the OpenStar office, with the view of Wellington harbor partly obscured by fusion math equations scrawled over the window in orange marker pen. “Fusion is one of the hardest things that humankind will have ever attempted. But it’s worth doing because of the transformative effect. It’s brave and hard.”

The next phase for OpenStar is to build the next prototype model, called Tahi, which Mataira aims to have operational in about two years. Within five years is targeted a third-generation model, called Maui, which will create neutrons and be revenue generating. Ultimately, the fourth-gen model, Tama Nui, may produce 50 to 200 megawatts of electricity, sufficient to support a small city or a large industrial operation.

Such an outcome is a way off and, for some, questions remain about how feasible this all is. But to Mataira, Tuesday’s demonstration not only shone a light on the company’s progress, the achievement also disproved doubts by skeptics over whether levitated dipoles could be engineered successfully — and in New Zealand.

He cites as an inspiration Ernest Rutherford, the New Zealand-born scientist who's considered the father of nuclear physics for splitting the atom in 1917.

“This story starts with Rutherford and it's going to end in New Zealand,” Mataira said. “We are the ones who are going to finish this race.”

©2026 Bloomberg L.P.