Wall Street Is Turning Climate Finance Into an Energy Security Pitch

(Bloomberg) -- Never before has New York climate week attracted so many people. And never before have the bankers attending been so keen to distance themselves from the traditional framing of climate finance.

Bankers interviewed by Bloomberg emphasized the need to finance the vast supply of energy required to power growth in artificial intelligence. The goal of energy security was also often invoked. Decarbonizing loan books, however, was treated as less of a priority.

“The green premium has gone, as has a lot of the fluff and froth, so the only things that will get funded are those that make economic sense,” said James Socas, a former executive at Blackstone Inc. and Investcorp who’s also an adviser with the center for private equity and venture capital at the Tuck School of Business.

“The narrative has had to change,” he said. “Rather than call something a ‘climate investment,’” bankers are now “more likely to get interest and sign-off” if they refer to a deal as targeting “energy security or energy for AI,” he said.

It’s a shift that’s upending the traditional understanding of climate finance. Back in 2021, when the world’s biggest banks and asset managers all signed up to net zero alliances, the oft-touted goal was to align portfolios with a target of limiting global warming to 1.5C. Four years later, bankers are now vying for deals that will add to the supply of energy. Much of that will be low-carbon, but banks no longer talk of applying restrictions to fossil finance.

The strategy is helping US banks toe the line on policies set by President Donald Trump. Aside from his full-throated support of fossil fuels, Trump has made clear that nuclear and geothermal power are his preferred forms of low-carbon energy.

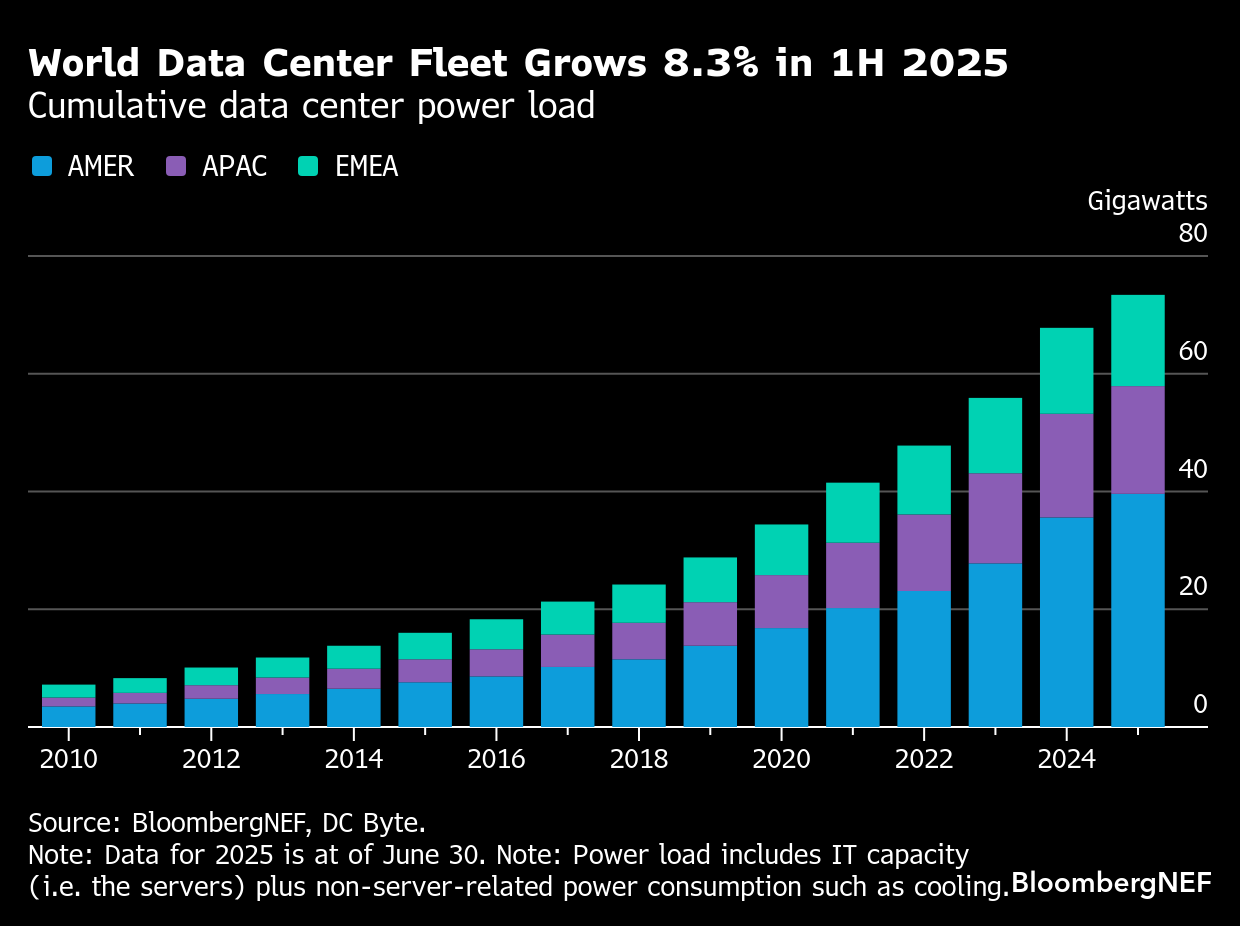

Financing the energy supply required to power AI is increasingly shaping how US banks approach transition finance. BloombergNEF estimates that data-center capacity is rapidly expanding among US companies developing AI, with electricity demand from AI training and services set to quadruple within a decade.

There’s also considerable evidence to show that the cheapest way to power AI is through renewable energy. BloombergNEF estimates that speeding up electrification and adding renewables has the potential to slash $19 trillion from fuel costs by mid-century. And the International Renewable Energy Agency notes that 91% of all newly commissioned utility-scale renewable projects delivered electricity last year at a lower cost than the cheapest new fossil fuel-powered alternative.

But for US bankers, branding a strategy as climate finance is an increasingly risky undertaking with Trump in the White House. The US president’s views on climate science once again made headlines this week, underscoring his administration’s willingness to crack down on policies that are clearly identifiable as pro-climate.

In Trump’s address to world leaders at the United Nations this week, he referred to renewable energy as a “joke” and singled out wind turbines as “pathetic.” He also called the very concept of climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world.”

As one senior banker interviewed by Bloomberg put it, no one on Wall Street wants to put their head above the parapet right now.

Against that backdrop, the US finance industry is continually trawling through changes in legislation or policy that may leave bankers in the crosshairs of the Trump administration. Of current concern is a recently signed executive order, said two Wall Street bankers who asked not to be identified discussing private deliberations.

The Guaranteeing Fair Banking for All Americans executive order, signed by Trump last month, has already been embraced by US regulators, including the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. The executive order, which doesn’t mention climate, targets “politicized or unlawful debanking.” People familiar with how some US banks are interpreting the order say there’s now concern it may be used as a lever to ensure capital isn’t withheld from the fossil-fuel sector.

As a consequence of the Fair Banking executive order, financial institutions may “face enforcement actions, and even civil liability,” law firm DLA Piper wrote in a recent note. “Banks, credit unions and other supervised financial institutions may anticipate an evolving supervisory, examination and enforcement environment.”

In light of the order, law firms are advising banks to review their policies and procedures to ensure they don’t fall foul of the spirit of the decree. According to a legal update by Luse Gorman, areas of interest include ensuring that oil, gas and energy companies have the same access to finance as other industries.

The current environment of political backlash against green policies in the US is bad news for climate investors with a short-term focus, Sarah Kapnick, global head of climate advisory at JPMorgan Chase & Co., said during a Bloomberg Green panel on Thursday. For short-term climate investors, the thesis has now been “blown up,” she said. But for long-term investors, it’s a very different story, she said.

“For the last few years, I saw a lot of enthusiasm to do leadership by press release before action actually happened,” Kapnick said. “We’ve been forced to have a reset of that where companies are now doing the deep strategy to try and figure out” how to actually deliver on their goals, she said.

Ultimately, the finance industry will find a way to act in its own economic interest as it always does, said Lisa Sachs, head of Columbia University’s Center on Sustainable Investment. The politics and the “framing” of issues “doesn’t change their assessment of financial risk,” she said.

At this year’s New York climate week — which is set to host more than 100,000 people, roughly twice as many as are expected to head to the COP30 climate summit in Brazil in November — there have been lots of conversations about the “reset” in green finance, according to a US private equity executive who asked not to be identified by name.

And while there’s a lot of focus on energy supply, there’s also an awareness among banks and investors that they need to protect assets from the physical fallout of climate change, the executive said. Asset classes seen as particularly vulnerable to valuation adjustments as a result of extreme weather events include real estate and infrastructure; these considerations are playing an ever bigger role in the due diligence that private equity firms do before agreeing to an infrastructure deal, the executive said.

It’s a consequence of climate change that’s increasingly hard to ignore, said Mindy Lubber, chief executive of the nonprofit Ceres. And ironically, as banks focus more on the financial rather than the “moral” side of greenhouse gas emissions, they’re learning that the potential losses of global warming are too big to ignore, she said.

It’s “no longer about compliance or reputation management,” Lubber said. “It’s about profit and resilience.”

(Adds comments from JPMorgan executive in 16th and 17th paragraphs.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.