China Played It Safe With First Pledge to Cut Greenhouse Emissions

(Bloomberg) -- China has finally set a goal to slash greenhouse gases from peak levels, using a United Nations climate event on Wednesday to outline its first proposed cuts to planet-warming pollution. The commitment falls short of what scientists estimate is needed to avoid passing the global warming limits enshrined in the Paris Agreement. It’s also less ambitious than cuts achieved by other countries, including Germany and Japan, after their emissions peaked.

But the announcement from Chinese President Xi Jinping in a video appearance at a special UN meeting in New York marks a turning point for the world’s biggest emitter. Previously, Chinese leaders had only pledged to reach peak emissions before 2030 and measured reductions in relation to economic growth. That means with its new climate goal China has committed to join the group of industrialized nations whose emissions are slowly but steadily going down.

The target to reduce greenhouse gases between 7% and 10% by 2035 follows a tradition of Chinese leaders setting modest climate targets, which the country has mostly exceeded. China’s 10-year goal for renewable energy, set in 2020, came to pass six years ahead of schedule. The track record of what other nations have actually achieved after reaching peak emissions may hold clues as to whether China can overachieve this target.

Listen to Zero: Have China’s Carbon Emissions Finally Peaked?

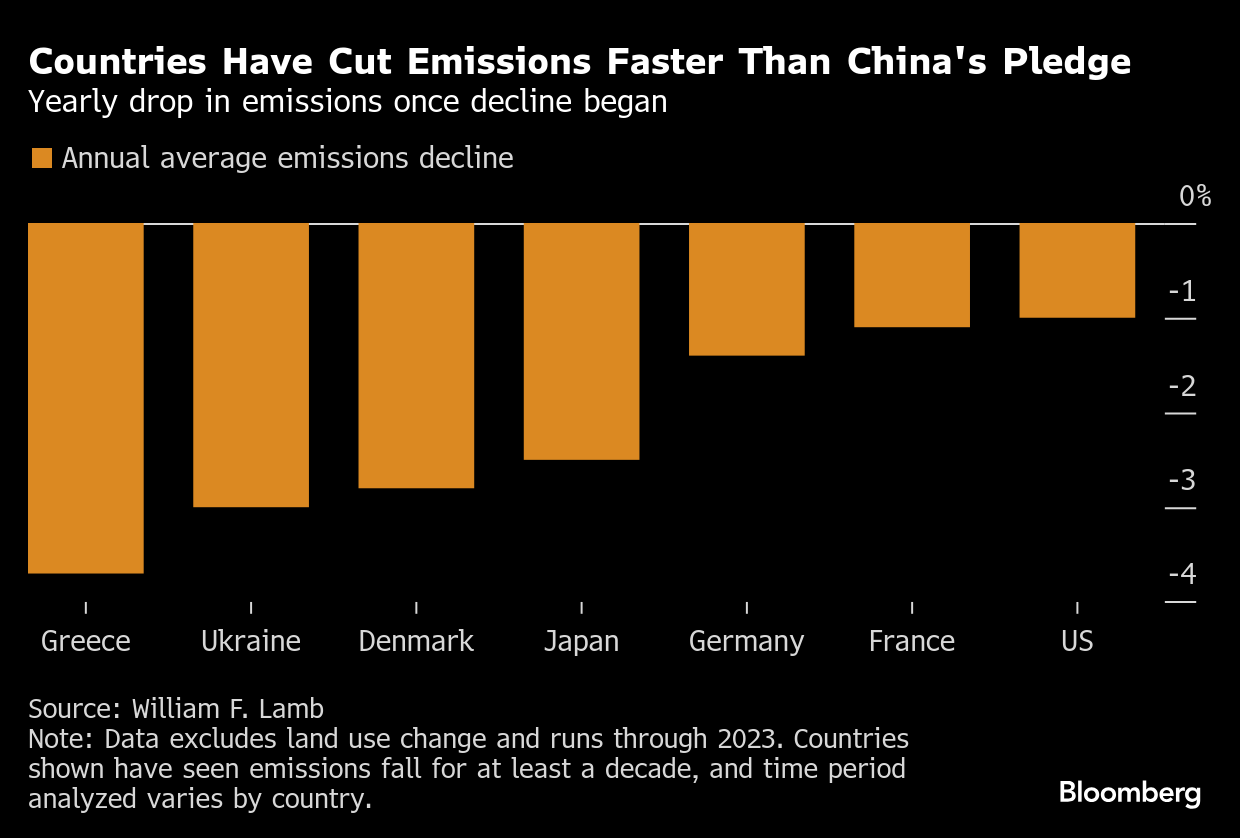

As of 2023, two dozen countries have managed to keep their emissions in decline for more than a decade, according to research by William Lamb, a senior researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Most of those nations saw their climate pollution fall at an annual average rate exceeding China’s pledge, which would require as much as 1% reductions per year from a 2025 starting point. Recent data suggests that China may have already reached peak emissions, even though Xi didn’t specify a starting year for China’s reduction target.

At the front of the pack, Greece’s emissions have dropped an average of 3.7% per year since 2005, while Ukraine has sustained annual reductions of 3% since 1990. Major Western economies have seen slower progress: around 1% annual cuts for France and the US, and 1.4% for Germany.

Some observers held out hope that a low target would not limit what happens next for the biggest emitter. “China has often under-promised and over-delivered,” noted Andreas Sieber, associate director of policy and campaigns at 350.org. The new climate target puts the country “on a path where clean tech defines economic leadership.”

Based on Lamb’s analysis, the actual path of decarbonization followed by countries after reaching peak emissions is often shaped by idiosyncratic factors. For Greece, the drop in emissions was largely a result of the 2010s economic crisis. Denmark proactively embraced policies supporting renewable energy as early as the 1980s. The US, meanwhile, benefited from the fracking boom, which displaced coal power and drove down emissions from a 2007 peak.

Much has changed since European nations first hit peak emissions. Many began their carbon declines in the 1990s, when there were fewer alternatives to fossil fuels and little global interest in addressing climate change. Today, China is the world leader in electric vehicles and renewable energy — both of which have become much cheaper — as well as many other green industries.

China could achieve a 30% reduction by 2035, according to modeling by the nonprofit Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. That would be on the low end of what researchers found would be needed to keep the 1.5C temperature target alive. It would require maintaining the current breakneck pace of clean energy deployment and electric vehicle sales, along with ambitious decarbonization policies in sectors that are currently lagging, including steel and buildings.

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at CREA, argues that Beijing could feasibly meet the goal. “Clean energy deployment, electrification, and structural adjustment of the economy away from the construction sector have only accelerated,” he said.

Other researchers see the 30% target as unrealistic. “That number is very challenging for China — for both internal and external reasons," said Hu Bin, an associate professor at the Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development at Tsinghua University. He pointed to major challenges in transitioning away from coal, getting clean energy onto the grid and developing enough energy storage.

Global trade tensions and the US retreat from climate action add more hurdles and unpredictability. The UN climate event on Wednesday saw a group of world leaders pledge new 2035 climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. But big emitters, including the EU and India, have yet to release updated climate pledges less than two months before the COP30 climate summit in Brazil.

While many Western nations reduced their emissions by moving dirty factories overseas, China is the world’s manufacturing hub and will have to largely green its industries at home. Hu said his institute estimates China will cut emissions 10% to 15% by 2035. “I am very confident that this number will be achieved,” he said. “Given the speed and scale and the price of renewables in China, it is possible that China will do better.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.