US Economy Wins From Green Exit, Unless the World Follows Suit

(Bloomberg) -- Slashing green energy goals and doubling down on fossil fuels, the kinds of policies President Donald Trump has been pushing, would benefit the US economy in the long run — and hurt countries still betting on the green transition.

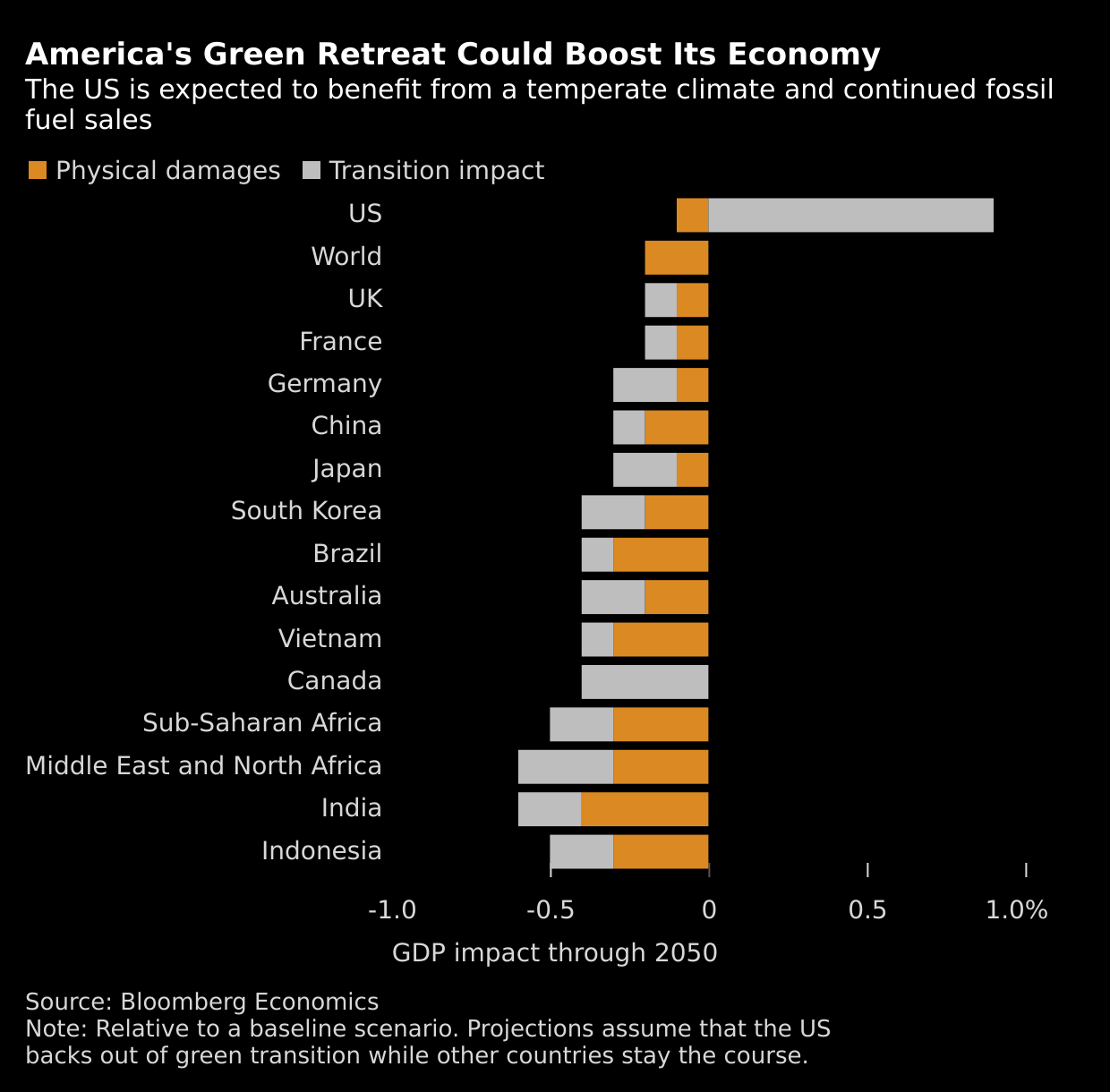

Economists from Bloomberg Economics looking at how climate change and the cost of curbing emissions will affect nations’ economies through 2050 found that by selling more fossil fuels and avoiding the expense of meeting green regulations, the US would see its GDP grow by about 1% more than it would have had it continued the clean energy transition. But assuming other countries plow forward with renewable energy, the world economy overall would shrink by 0.2% compared to the baseline scenario, according to the modeling.

While these economic effects may look modest over the next 25 years, most of the physical damage from global warming is expected to happen after 2050, increasing the economic costs of extreme weather and other consequences of climate inaction for everyone, the researchers said. There's also the added risk that climate change could accelerate in irreversible ways, they said.

“If Trump alone backs out on the transition, the US wins,” Bloomberg Economics’ Eleonora Mavroeidi and Maeva Cousin, who co-authored the new report, write. “If other countries do the same, the US loses, and so does almost everyone else.”

This illustrates a classic economic concept known as the tragedy of the commons, in which different actors pursuing their own best interests can lead to worse overall outcomes, Mavroeidi and Cousin say.

The US’s about-face on climate policies will be evident at the upcoming COP30 climate conference in Belém, Brazil. High-level US representatives are skipping it, leaving the rest of the world to sort through thorny issues such as 2035 emissions goals and scaling climate finance for developing nations and small island states.

The Bloomberg Economics analysis assumes the US abandons is all out when it comes to renewable energy goals while and the rest of the world presses on with them over the next 25 years. Reality is likely to be more complicated. Last month, for example, US pressure led countries to put off voting on a landmark regulation to make the shipping industry start paying for its emissions.

In addition to being the world’s second-largest polluter, the US is also a major oil and gas producer, providing power both domestically and to other countries. Over the summer, the Trump administration reached a trade deal with the European Union that included commitments by member countries to buy $750 billion in US oil, natural gas and nuclear energy.

By expanding these kinds of policies, the US would become more competitive in the fossil fuel market, allowing the industry to gain market share, as the country sidesteps some of the green transition costs.

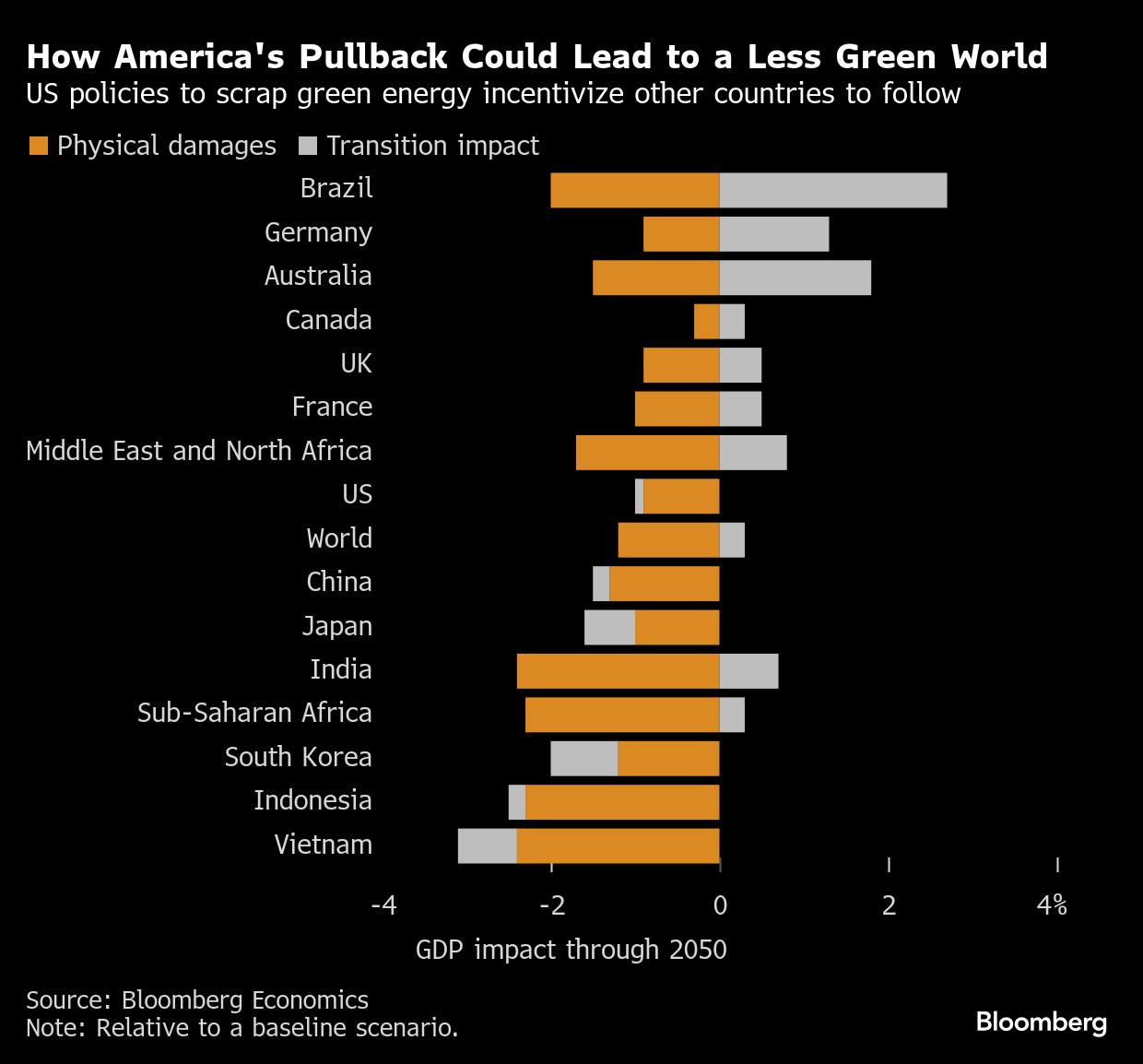

But another outcome from the US backing out of green policies could be that it incentivizes other countries to do the same, the researchers say. If that happens, the US would also be worse off, according to the model.

Its economy, along with the global economy, would each contract by roughly the same amount, about 1%, compared to a scenario in which all countries continue to pursue renewables. Global CO2 emissions would also increase around 75%.

Hotter, lower-income countries are expected to face some of the greatest fallout from climate change regardless of whether most of the world sticks with the green transition or not. The modeling found that India, Vietnam and Indonesia are the biggest losers, with sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa also suffering. Cooler, wealthier countries, meanwhile, like the US and Canada, are more insulated and therefore expected to have smaller losses.

Bloomberg Economics’ modeling was based on BloombergNEF projections of energy demand and supply, which factor in, among other things, higher energy demand due to the proliferation of AI data centers. The economists then used a large-scale model of the global economy to evaluate how a US policy pivot could play out for the economy, emissions and climate damages.

“Doing nothing is a costly strategy, especially for countries already facing intense heat with a limited capacity to adapt,” write the authors. “Richer countries are initially affected less severely but would also see their costs climb over time.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.