Carbon Dioxide Emissions Are Set to Reach a New High This Year

(Bloomberg) -- Global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil-fuel use will reach a record high this year despite countries’ pledges to begin lowering their climate pollution.

Emissions are projected to hit 38.1 billion tons, a rise of 1.1% compared to last year, according to the 20th annual Global Carbon Budget. The rise in atmospheric CO2 comes as the amount taken up by oceans and land shrinks, adding urgency to the COP30 climate talks happening in Brazil.

While the uptick in emissions has slowed since the 2000s, “we’ve been saying this thing for way too long,” said Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project and chief research scientist at Australia’s CSIRO Climate Science Centre.

The extraordinary explosion of renewables and gradual decline of emissions growth mean that “this is not just a negative story,” he said, “but it is a story of bitter-sweetness.”

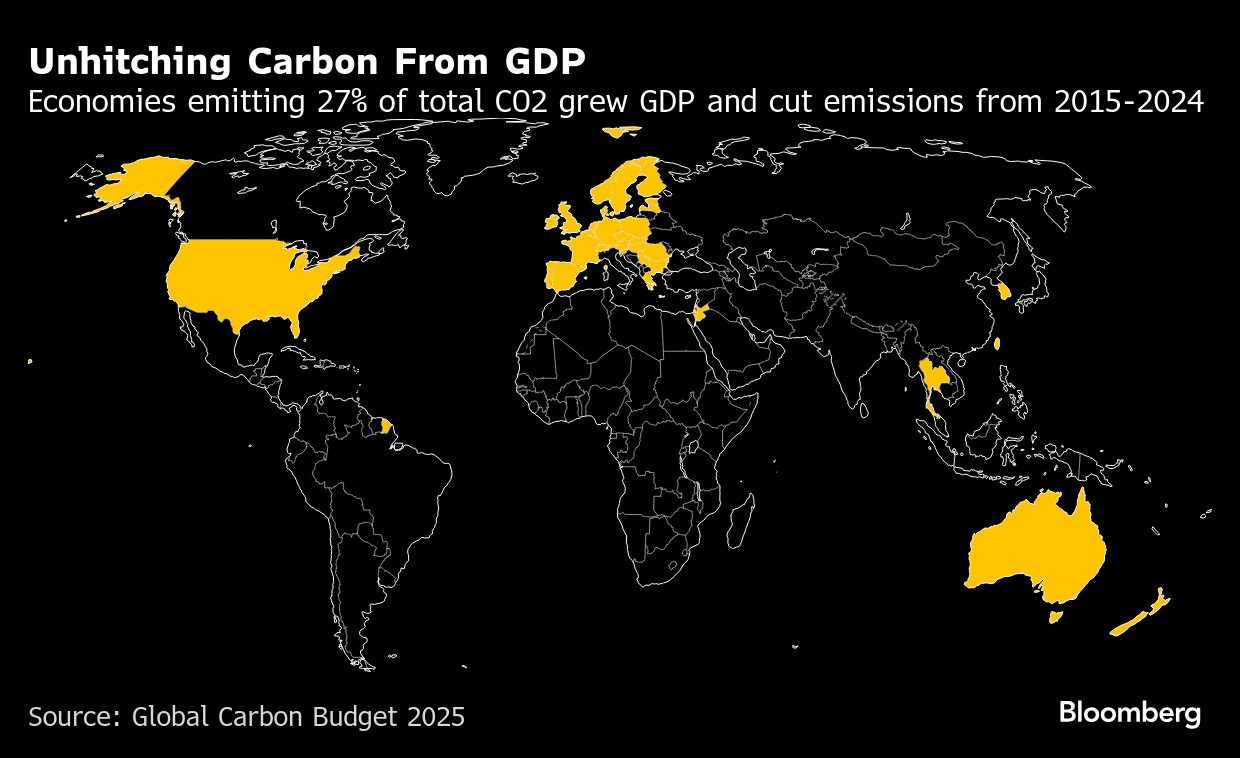

The Global Carbon Project’s annual top line number is a quick barometer of the world’s lack of progress in cutting emissions, but the country-level details show key differences. The US is responsible for more CO2 historically than any other country and ranks second annually. Its fossil-fuel emissions are expected to rise 1.9% in 2025, compared with a 10-year average of 1.2% annual declines.

China is the world’s biggest annual polluter, but the country’s emissions have been flat or falling for 18 months. Its fossil-fuel emissions may grow this year by 0.4%, though the range in the new report reaches from a -0.9% to 2% change over last year. India, the third biggest annual emitter, will see CO2 output grow by 1.4%, a growth rate lower than the past few years. Some sectors have seen big rises, though: Global aviation pollution, for example, is up 6.8%.

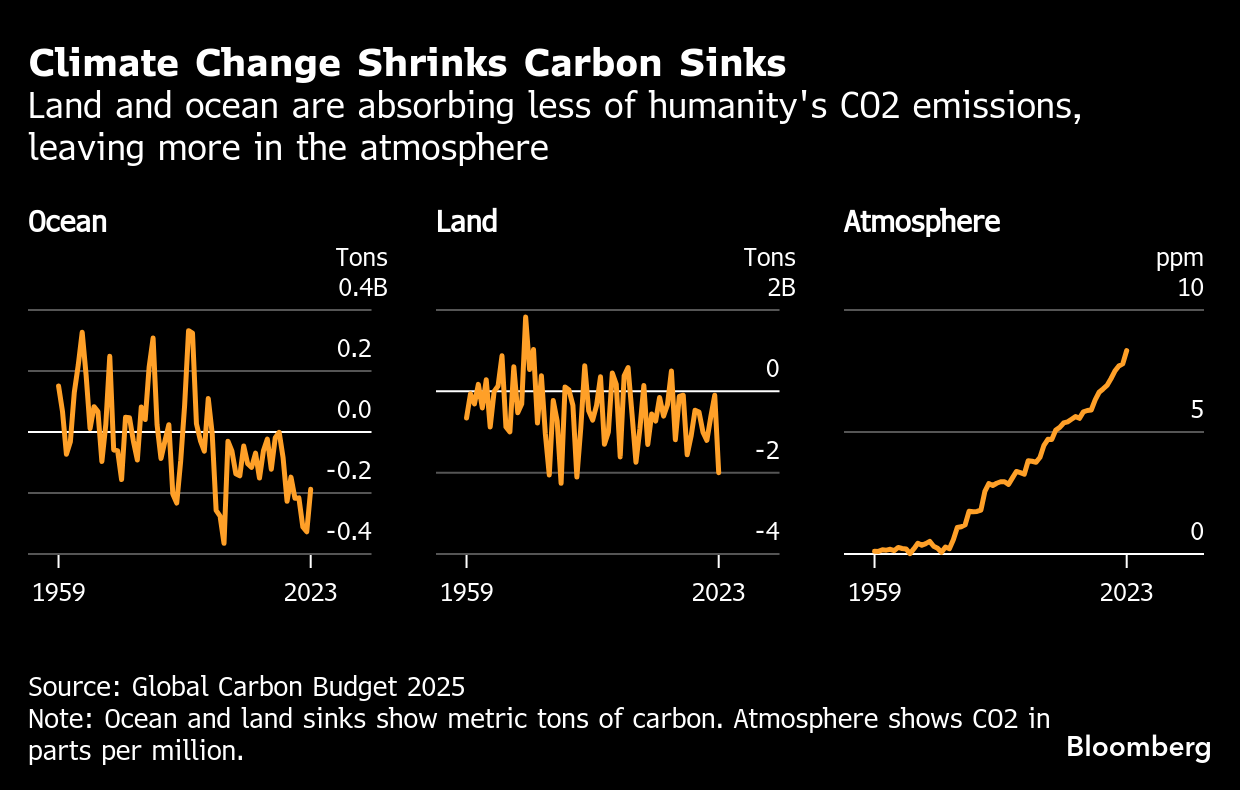

About half the emissions humanity puts in the atmosphere are absorbed by the oceans and land — so-called carbon sinks. Previous estimates indicate that land took in as much as 30% of the CO2 burden while oceans absorbed roughly 25%.

But the Global Carbon Project updated its approach this year, drawing on new research to refine those estimates and ensure the carbon budget is properly balanced. By accounting for changes in land cover over time — including climate impacts, such as heat, drought and wildfires — they found the amount of carbon going into forests and land “is substantially smaller than previously estimated.” At the same time, recent observations show the oceans absorb more carbon than model estimates.

Using the updated findings, the Global Carbon Project now estimates that over the past decade, oceans have taken up 29% of human-generated CO2 emissions and land has captured 21%.

Crucially, though, the new report shows that both ocean and land are absorbing less and less of humanity’s carbon pollution. On land, deforestation continues to ravage forests while rising temperatures intensify dryness and drought. In the ocean, warming water store less carbon while changes in wind patterns mean less mixing between the air and sea, reducing carbon uptake.

The world has already heated up by nearly 1.4C (2.5F), according to the report, and more planet-warming CO2 staying in the atmosphere could accelerate climate change.

Calculating the carbon budget, including how much more humanity can emit before breaching key global temperature targets outlined in the Paris Agreement, is vital for developing the world’s and individual countries’ emissions-cutting goals. An ever-finer understanding of how much forests and oceans absorb CO2 — or fail to — focuses attention on how to preserve them and on the importance of winding down fossil-fuel use for cutting climate risks.

At COP30 talks in the Amazon, forests have been a particular focus. Brazil has pushed create a $125 billion fund to protect tropical forests, though it’s raised $5.5 billion so far. The new report shows the risks the land and ocean sinks are facing, and why conserving them is so important in the face of rising emissions.

“That's what we show and quantify,” said Judith Hauck, a Global Carbon Budget co-author and a marine biogeoscientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute. “It really is the big life support system that we have.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.