Brazil's Green-Energy Industry Is Falling Victim to Its Own Success

(Bloomberg) -- In just a few months, Brazil will host the world’s biggest climate summit. But as the country prepares to welcome thousands of dignitaries to debate plans to tackle global warming, its own wind and solar industries are flailing.

The casualties are piling up. 2W Ecobank SA, a wind energy producer, filed for bankruptcy protection in April. Rio Alto Energias Renovaveis SA, which constructs and operates solar energy projects, went to court to ask for temporary protection against creditors as it tries to restructure debt. Aeris, the biggest producer of blades for wind farms in Brazil, restructured its debt after more than 3,700 job cuts.

Brazilian wind and solar companies are facing challenges that mirror the plight of clean-energy projects around the world: permitting delays, a dearth of transmission lines, supply-chain snags and high borrowing costs. The setbacks are so severe that they’re putting the world’s green-energy goal — to triple renewable power capacity by 2030 — in peril.

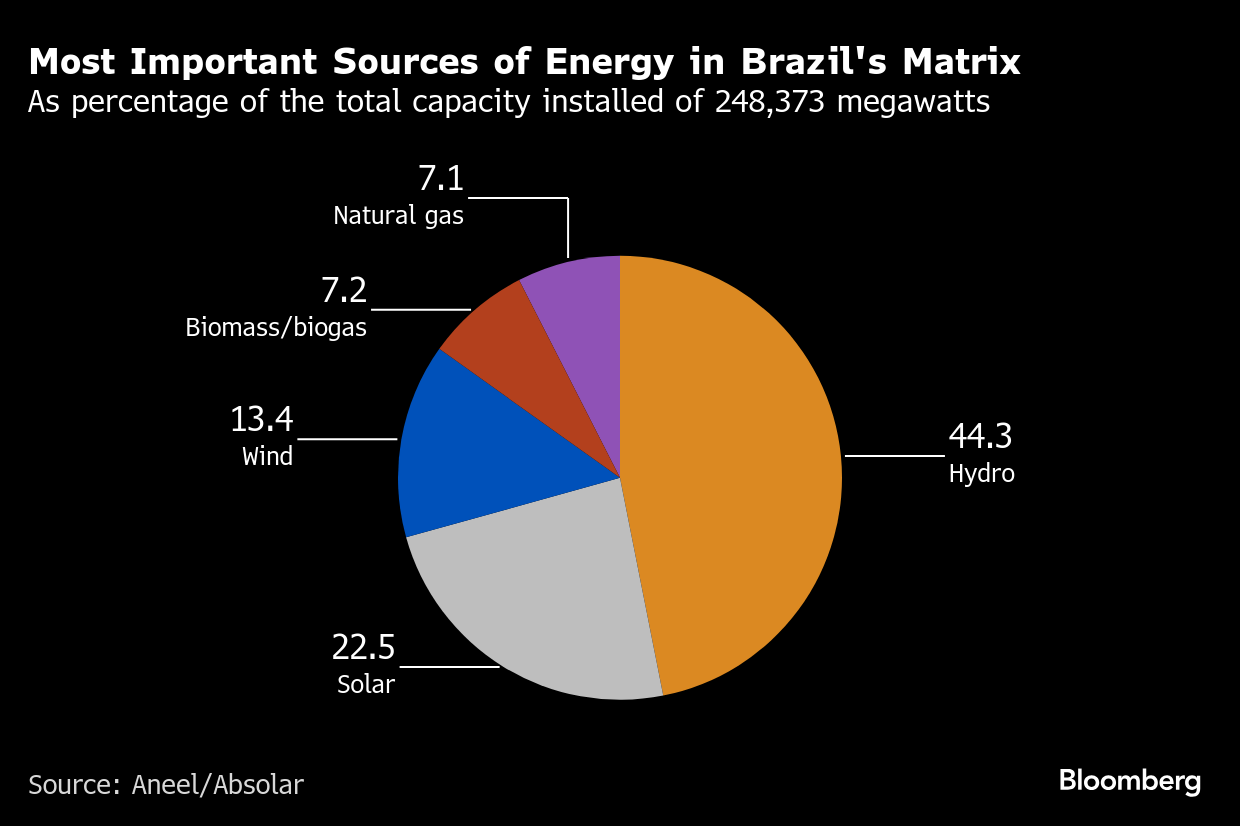

In contrast to the US, where President Donald Trump’s anti-renewables policies have hammered the industry, Brazil has remained a staunch supporter of green energy. A major hydropower producer, it has the cleanest energy mix of any G-20 country by a wide margin. It also clinched third place globally in new capacity for wind and solar last year.

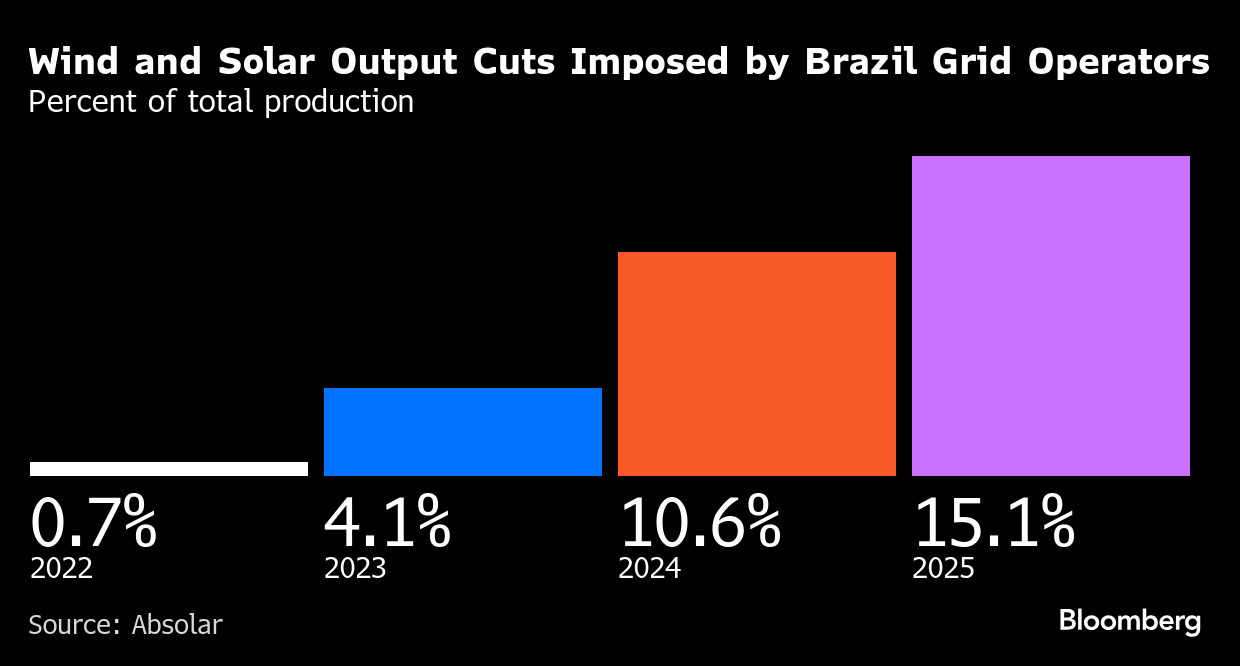

But Brazil’s renewables industry has been, in part, a victim of its own success. The production boost from new wind and solar sources created an excess of power in the daytime and there aren’t enough transmission lines to absorb all the electricity, forcing grid operators to limit output from those projects. The nation’s energy-related emissions still need to drop steeply to reach net zero by 2050, according to BloombergNEF — a goal that could be further endangered by the renewables sector’s woes.

“We are living through the worst of times” for Brazil’s energy industry, said Elbia Gannoum, president of Abeeolica, a national association that represents wind farms. “It’s the first time I’ve seen a crisis of this scale and duration. This is not something that will be resolved tomorrow,” she said in an interview.

Rio Alto Energias declined to comment, while 2W Ecobank didn’t respond to requests for comment. Aeris said the company has renegotiated 90% of its debt and is still in discussions to restructure its remaining borrowings, “paving the way for a sustained improvement in its financial situation.”

The trouble is so widespread that Abeeolica and Absolar, Brazil’s solar industry association, have been asked to talk to banks and investors to help extend debt maturities so companies facing revenue reductions of as much as 60% can survive the short-term crisis.

“The loans and bonds will be paid, but people need to understand that the sector is going through an exceptional situation,” Rodrigo Sauaia, chief executive officer of Absolar, said in an interview. “It’s in the interest of investors and banks to weather this storm together with the industry.”

Banco BTG Pactual SA and Banco Santander Brasil SA are among the creditors of some of the distressed Brazilian wind and solar companies, along with government-owned lenders like BNDES and Banco do Nordeste do Brasil SA. Investors including JGP Gestao de Credito have also been affected. BNDES and JGP declined to comment, while BTG and Santander didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“We received some specific demands to negotiate due to production cuts and we were able to advance, without problems, stress or lack of payment,” Luiz Abel, a business director from Banco do Nordeste do Brasil, said in an interview. While “the losses are accumulating for the companies,” BNB’s loan book is healthy and has solid guarantees, he said. He confirmed he had discussions with the industry’s associations but said it’s better to treat the situation on a case-by-case basis.

High interest rates have been a challenge, with Brazil’s central bank increasing basic rates to 15% last week, the highest level since 2006. Some of the lending for the solar and wind energy industry is subsidized, however.

For wind power parts suppliers, lower production and factory shutdowns led to 11,000 job cuts between 2024 and 2025, according to a survey by Abeeolica.

“The crisis is very deep in the wind energy because the supply chain is 80% in Brazil,” Gannoum said.

Developers of wind and solar projects face transmission constraints around the world, including in the US and Europe. In Brazil, the problem is particularly acute, as most of the power is produced in the Northeast and consumed in the Southeast.

The country’s grid operator started cutting wind and solar energy output in 2020 due to falling demand during the pandemic. But after fluctuations in wind and solar power played a significant role in a blackout that affected much of the country in 2023, the operator tightened production limits. In February, the restrictions became even more stringent after a transmission line collapsed, said Fitch Ratings Inc. and Absolar.

Through 2029, wind and solar curtailments are poised to increase when generation exceeds demand, especially in the daytime, Brazil’s National Electric System Operator, ONS, said in a report earlier this month.

Under a 2004 law, wind and solar producers were fully reimbursed by consumers through power bills for losses from output limits. But a rule from regulator Aneel in 2023 means that those companies can now recoup at most only 3% of their losses, while thermal power plants continue to receive the full amount, according to Absolar.

Absolar and Abeeolica are suing Aneel for reimbursement of losses that include 4.8 billion reais ($873 million) already incurred by member companies as a result of the production limitations. Aneel didn’t respond to a request for comment. Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy, which created a committee with industry representatives to address the power cut situation, also didn’t respond.

Renova Energia SA, a wind and solar operator, recently emerged from bankruptcy. The company achieved significant progress last year “even in the face of ongoing challenges in the Brazilian electricity sector” and will make investments aimed at expanding its installed capacity, according to a statement.

“As long as we don’t have a large number of transmission lines to transport this energy, we will continue to see a lot of curtailment,” said Thaina Cavalini, associate director for infrastructure and project finance at Fitch.

Gannoum disagrees. To her, the major problem is small-scale solar power generators that are using government subsidies to produce power not just for their own consumption but mainly to profit, creating too much electricity during the day. This type of generation isn’t affected by regulatory curtailments, which only apply to larger producers, and already accounts for more than 15% of the total capacity installed, she said.

While the government plans to buy batteries to help the grid store more power, those auctions have been postponed to the second half of the year, Cavalini said. Many companies can’t afford to invest in batteries themselves because the taxes on those systems can reach 85%, according to Absolar.

Fitch has a negative ratings outlook for three Brazilian renewable energy companies because of the power output cuts: Serra do Mel Holding SA, Itarema Geracao de Energia SA and Complexo Morrinhos Energias Renovaveis SA, an AAA-rated company controlled by China’s CGN Brasil Energia SA. CGN Brasil declined to comment, while Serra do Mel and Itarema Geracao didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Brazil’s Northeast should build data centers and pursue green hydrogen projects to absorb the surplus energy, Eduardo Sattamini, the head of Engie SA’s Brazil operations, said during a meeting with journalists in May.

“It’s important that the creation of this demand is done in the locations where there’s a surplus of supply,” he said.

The country has attracted billions in investments for power line projects to connect renewables to its largest consumer markets, but these projects can take almost a decade to start operating. Brazil's next power line auction is expected to take place in October.Some Brazilian renewable energy companies are trying to attract partners or sell their businesses. Equatorial Energia SA, an energy distributor, hired Banco Safra SA to try to sell wind and solar energy generator Echoenergia Participacoes SA, a company it bought for 7 billion reais in 2022, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg News in October. Equatorial Energia didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Other companies are simply shutting operations. Massachusetts-based GE Vernova Inc. said it February that it would close LM Wind Power’s wind blade factory in the Brazilian city of Suape, cutting 1,000 jobs, due to falling demand in the Latin American market.

For now, the prospect of a rebound in Brazil’s clean-energy industry remains a distant prospect, Absolar’s Sauaia said.

“The patient is in the ICU,” he said. Before any type of recovery can happen, the industry “must first stop breathing through machines.”

(Adds Sattamini quote in 26th paragraph)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.