Europe’s Climate Resolve Faces Test as EU Unveils 2040 Goal

(Bloomberg) -- The heat wave searing Europe is making a compelling case for one of the most ambitious climate targets ever set by Brussels. Many in the European Union, however, have yet to be convinced.

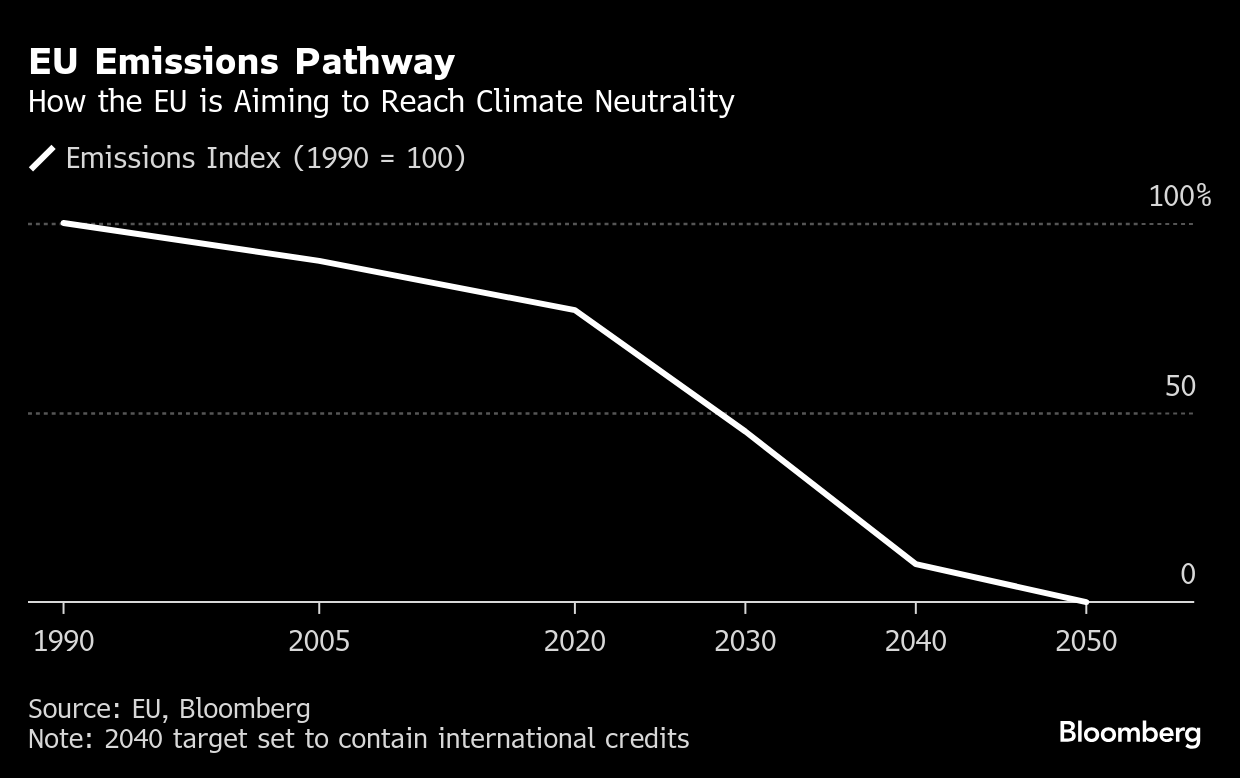

The European Commission, the EU’s executive branch, proposed Wednesday a binding law to slash emissions by 90% by 2040 as part of its overarching goal to reach climate neutrality by the middle of the century. While that shows the bloc is still up for the fight against global warming, it’s been forced to offer various “flexibilities” to help countries meet the target.

“Industry and investors look to us to set a predictable direction of travel,” said Ursula von der Leyen, commission president. “Today we show that we stand firmly by our commitment to decarbonize European economy by 2050. The goal is clear, the journey is pragmatic and realistic.”

With US President Donald Trump withdrawing from the landmark Paris Agreement for a second time, there’s pressure on Europe to take the initiative. But the region’s leaders are also distracted: ramping up defense spending, engaging in a trade war with Washington and trying to defend historic industries being squeezed by high energy prices.

As the stage is set for months of hard bargaining, here’s what’s at stake:

The Goal

The 2040 target has been delayed for months as Wopke Hoekstra, the EU’s climate commissioner, toured capitals to drum up support for a 90% net emissions-cutting goal that scientists say is the minimum for the bloc to meet its climate obligations. He also needed to await the outcome of key elections in Germany and Poland.

The message he received was clear: without sufficient flexibilities and a number of so-called enabling conditions — like investing in power grids — Hoekstra would not secure a majority in the European Parliament, nor the weighted majority of countries in the EU council that he needs to back the target.

“We don’t see a majority in parliament nor council for any 2040 target without flexibility,” said Peter Liese, a lawmaker for the center-right European People’s Party, the largest group in parliament. “Finally Europe will create the enabling conditions to actually reach any 2040 target.”

The Solution

Hoekstra’s solution rests on countries being able to use cheaper United Nations-administered international carbon offsets to meet around 3% of the 2040 target. Yet it’s unclear how exactly that will work, especially after a previous experiment with international credits under the Kyoto Protocol proved a disaster.

What we know is that, unlike previous attempts, they will not enter into the EU’s Emissions Trading System and they’ll only be allowed from the second half of the decade. Host countries that provide credits must also have their own climate ambitions in line with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. The commission said it would favor technological removals.

“These international credits must therefore come from credible and transformative activities, such as direct air carbon capture and storage and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage,” it said in a question and answer document.

Doubts remain, however, over whether there will be enough high quality credits available, and how much they’ll cost. The Article 6 UN rules, finalized last November, will also probably need to be phased out before mid-century because the EU’s 2050 climate neutrality goal doesn’t allow their use.

Political Hurdles

The 2040 target will only enter into force following negotiations with the EU’s 27 member states and the parliament. There are already tensions over the level of ambition and how quickly an agreement needs to be reached.

A group of EU leaders, including French President Emmanuel Macron, raised the issue of the target at a leaders summit in Brussels last week, highlighting the need to ensure that decarbonization and competitiveness go hand in hand. Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala rejected the 90% cut outright, calling for a realistic goal. It would only take France and a few smaller member states to derail the 2040 target.

Things aren’t much easier in the European Parliament, where the largest group, the EPP, is split over how aggressively the EU should pursue its climate goals. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who comes from the center-right group, is walking a tightrope to keep her centrist coalition intact: the socialists and liberals are demanding she stick to her green agenda, or risk losing the support of her two biggest allies in the assembly.

International Obligations

Part of the reason the commission says it needs to put forward its 2040 goal now is so that it can submit an updated 2035 climate plan, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution, or NDC, to the UN by September. Countries are due to meet in Brazil for COP30 two months later to discuss how far off course the world still is.

Wars, Trump and Climate Malaise: Brazil Braces for a Tough COP30

The commission wants to derive its 2035 goal by drawing a line between 2030 and 2040, which would equate to an emissions cutting ambition of around 72.5%.

The challenge is that the NDC requires a consensus among all 27 member states, so any lingering doubts could force the EU to put forward a weaker goal, potentially damaging the bloc’s reputation as a climate leader.

(Updates to reflect proposal being unveiled.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.