Airlines Trying to Reduce Emissions With Green Jet Fuel Face Reality Check

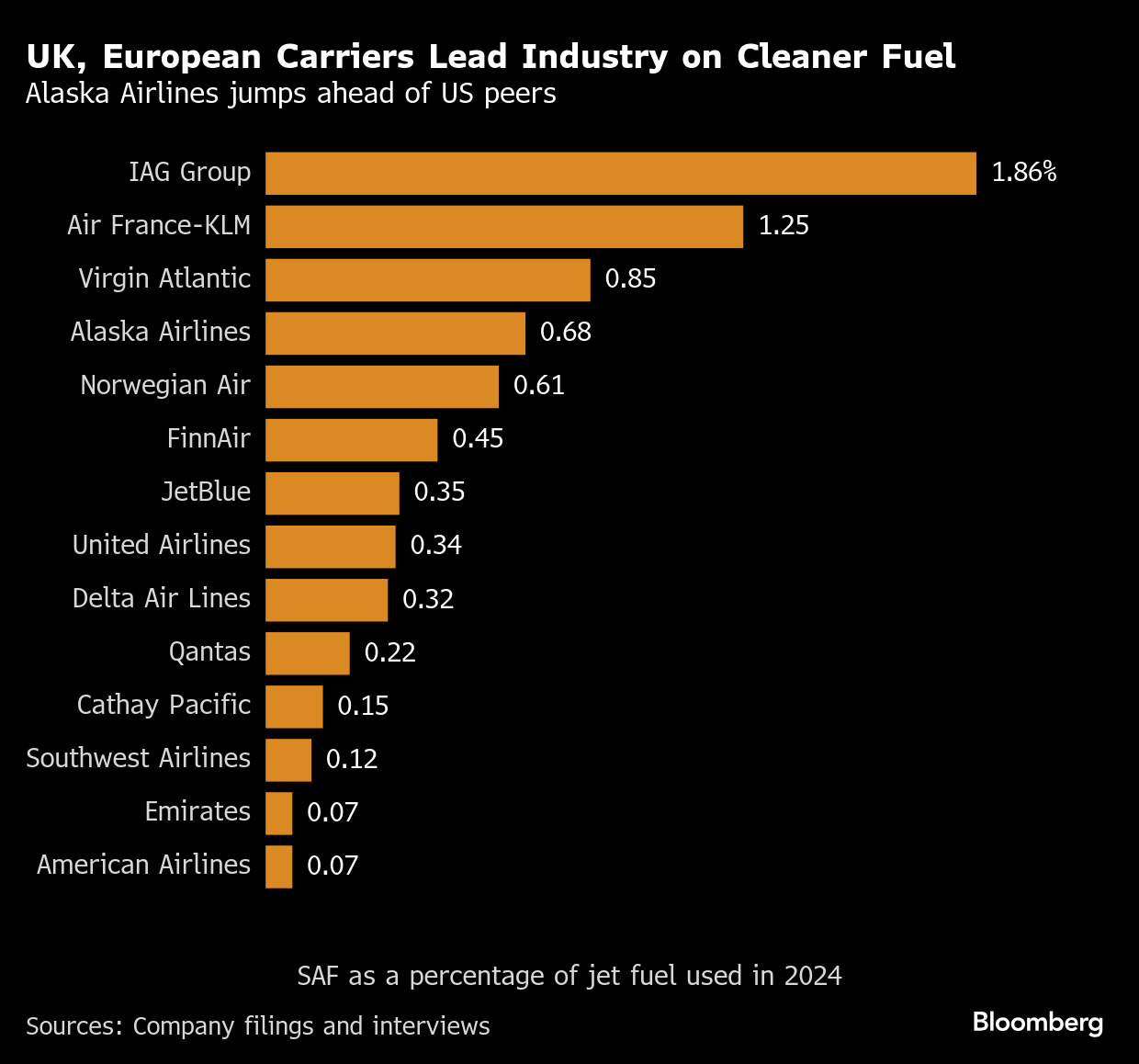

(Bloomberg) -- British Airways’ parent company IAG SA surged ahead of other passenger airlines last year to consume the most sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF, according to a review of corporate filings from dozens of air carriers.

The company acquired 55 million gallons of cleaner jet fuel, which is derived from lower-emitting sources such as used cooking oil and animal tallow. That number exceeded the amount used by all US passenger airlines combined.

But the promising performance is overshadowed by a troubling reality for the industry: The shift to SAF is still minuscule, while growth in passenger air travel is drowning out any climate gains so far. For example, despite IAG’s world-leading status, cleaner fuel accounted for only about 1.9% of its overall fuel consumption last year, and its emissions from fuel combustion still rose by 5%.

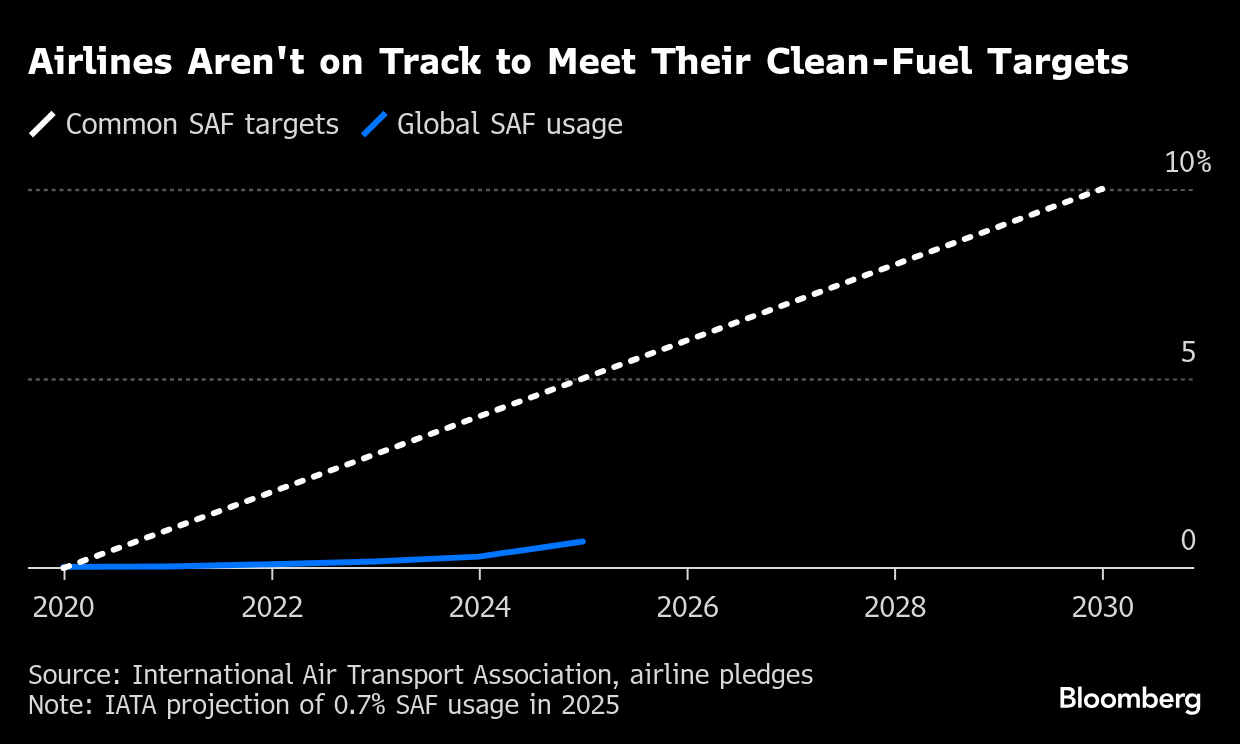

Globally, SAF is expected to increase to 0.7% from 0.3% of aviation fuel this year. But the International Air Transport Association expects air travel to climb 6%, causing another jump in emissions.

“We’re still at the very beginning of this market,” said Daisy Robinson, a BloombergNEF analyst who focuses on renewable fuels. “It’s going to take some time.”

New rules are springing up in different parts of the world to spur more use of SAF, which costs at least twice as much as conventional jet fuel. Starting this year, the European Union and the UK require jet fuel to include at least 2% SAF. Other requirements have been enacted or planned in British Columbia, Brazil, Indonesia and Singapore.

Such rules help protect first movers from being undercut on prices by competitors. “As airlines, because of competition, we’re not great at doing this voluntarily,” said Aaron Robinson, IAG’s vice president for sustainable aviation fuels in the US. “Mandates in different geographies can play a really important role in moving the whole aviation industry forward.”

In the US, where no mandates are planned and where President Donald Trump’s recent tax bill reduced incentives for SAF, airlines have fallen behind the market leaders (despite some heavily advertising their pursuit of greener fuels).

Alaska Air Group Inc. leapt to the front of US carriers last year by increasing its SAF usage more than tenfold to 0.68% of its fuel. That’s about double the percentage of several other big US airlines, including JetBlue Airways Corp., United Airlines Holdings Inc. and Delta Air Lines Inc. It’s nearly 10 times the percentage of American Airlines Group Inc., which used only 0.07% SAF. (When including cargo carriers, DHL Group led the world by using SAF for 3.52% of its jet fuel last year.)

Businesses that spend a lot on corporate travel, such as tech firms and consulting companies, helped pay for more than half of Alaska’s SAF last year. This enables companies such as Microsoft Corp. and Autodesk Inc. to claim a smaller carbon footprint. Microsoft shaved its emissions by 65,000 tons last year by helping cover the cost of greener fuels, including for some employee flights on Alaska.

It’s not clear, though, how many more companies will step up, especially given the high cost of cleaner jet fuel, compared with other options to rein in emissions. Ryan Spies, managing director of sustainability for Alaska, estimates that businesses pay between $150 to $300 for each ton of CO2 that they avoid through SAF purchases. By comparison, carbon offsets sold for an average of about $6.30 per ton last year, according to Ecosystem Marketplace (though many offset projects have delivered fewer climate benefits than advertised).

“This pool might not be that deep,” Spies said. “The only way to bring these [cost] numbers down is to invest in these technologies.”

Global SAF production continues to lurch forward at an uneven clip. While analysts say there’s plenty of green fuel to hit the 2% mandates in Europe this year, vastly more will be needed for airlines to reach their widely held goals of 10% SAF by 2030.

A couple of new plants began churning out cleaner fuels last year, including a large Texas facility from Diamond Green Diesel, which is a joint venture between Valero Energy Corp. and Darling Ingredients Inc. Meanwhile, World Energy’s first-in-the-country SAF plant in Paramount, California, has been shut down for months following the loss of financial backing from Air Products and Chemicals Inc. A World Energy spokesperson said there’s no timetable for restarting the plant.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment for airlines has been the retreat of oil giants, which previously trumpeted massive commitments in this area. BP Plc, for instance, said two years ago that it was pursuing five projects around the world that would produce 50,000 barrels of renewable fuels per day, with a focus on SAF. The oil major has since scaled back most of these plans amid a renewed focus on fossil fuels. BP didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“We need to make sure that some of these bigger players are really investing in the new facilities,” said Hemant Mistry, director of net zero transition for IATA. “They’re the ones who have the technical expertise, the experience, and they have the balance sheets, as well.”

Passenger air travel is expected to double by 2050, which will likely cause emissions to soar. While airlines are counting heavily on cleaner fuels to save the day — IATA anticipates SAF could be 80% to 90% of the fuel supply by mid-century — others are more pessimistic. BloombergNEF, for instance, predicts that scarce feedstocks and a lack of new plants will limit these cleaner fuels to about 7% of the industry’s propellant by 2050.

Considering these challenges, some in the industry are pushing it to shift its focus beyond SAF and to address the thorny issue of ever-rising passenger numbers. “Limiting or even questioning growth, that is difficult for airlines,” said Karel Bockstael, a former vice president of sustainability at KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, who retired in 2022 after 32 years at the company.

Bockstael last year co-founded the group Call Aviation to Action, which has the support of over 400 current and former aviation insiders, including from fuel producers, airports and airlines. They’re urging the industry to set firm limits for its emissions and to support more aggressive policies to stay within these boundaries. This could include levies on frequent flyers or carbon taxes on jet fuel.

“We’re not against the industry, we love it, we know all the benefits of it,” said Bockstael. “But if we do not have a strategy — if we do not have a way out when planetary boundaries are forced upon us — then we will have serious problems, and our industry will have a tragic hard landing.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.