In Fraught US Energy Fights, ‘All of the Above’ Is Now Democrats’ Pitch

(Bloomberg) -- The governor was fuming. The federal government had just pulled funding for what could have become a multi-billion-dollar energy project to fuel ships, trucks and buses in one of America’s largest industrial states.

“No matter what DC tries to dictate,” he raged at this intervention to withdraw government support, “we’ll continue to pursue an all-of-the above” strategy.

These type of demands for inclusive energy policies became widespread during President Joe Biden’s term, when Republican politicians and their oil industry backers routinely castigated Democrats for restricting fossil fuels while subsidizing low-carbon technologies. On this view, it’s the role of markets — not the government — to determine how Americans fuel their cars and power their homes.

But the angry governor in the example above from earlier this year was California’s Gavin Newsom, a Democratic front-runner for the next presidential contest and the party’s loudest critic of President Donald Trump. Echoing recent Republican attacks, Newsom called out Trump’s decision to pull money from a West Coast clean-hydrogen energy hub as an ideological move that’s the antithesis of “common sense.”

It’s a sign of how all-of-the-above energy politics have suddenly changed in 2025. In the latest example this week, the Trump administration suspended leases for all five wind farms under construction off the East Coast. Meanwhile, Newsom, a staunch clean-energy supporter, has spent recent months promoting more oil production, reducing fossil fuel regulations and nixing plans for a profit cap on refineries.

Sensing that plug prices are replacing pump prices as a key political battleground, some prominent Democrats are now taking on the all-of-the-above mantle as quickly as Trump and his allies are abandoning it in their drive to curtail renewable-energy projects. The governor-elect of Virginia, Abigail Spanberger, ran on an all-of-the-above energy policy in the country’s top location for power-hungry data centers. Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro calls himself “an all-of-the-above energy governor” while running a key swing state. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s recent embrace of natural gas is part of her plan to boost “reliable and clean” power, in a textbook example of all of the above.

“There’s clearly a political motivation for it,” said Ben Cahill, director of energy markets and policy at the University of Texas at Austin. “Democrats have realized that affordability is going to be a big issue in the next election season.”

The play for energy’s center ground is made possible by Trump’s aggressive moves to kill wind and solar projects at a time when power demand is expected to grow 35% by 2040 due to the unprecedented build out of data centers for artificial intelligence. Nationally, electricity costs rose 5.1% in the 12-month period ending in September 2025 and are expected to rise further as the power system undertakes upgrades to cope with extreme weather made worse by climate change.

Trump’s moves against renewable energy contradict more than two decades of GOP policy. Since George W. Bush’s presidency, Republicans have combined support for oil and gas with backing for growth in wind and solar power. The focus on energy abundance — rather than elimination — fit well with Republicans’ preference for free markets. Crucially, it also acted as a rhetorical shield for oil and gas interests in a world that increasingly viewed fossil fuels as the major cause of climate change.

“Don’t pick winners and losers,” Exxon CEO Darren Woods said in a speech in California in 2023 in which he warned against turning oil companies into villains. “We need an all-of-the-above approach. It’s far too early in the process to rule out any technology.”

But Trump has transformed the Republican position into a preference for some energy resources and opposition to others. He declared an energy emergency in January to wield sweeping Cold War-era powers to fast-track pipelines, expand power grids and save struggling coal plants while encouraging oil producers with constant calls to “drill, baby, drill.”

Those efforts are increasingly twinned with attempts to stifle clean energy. After announcing a withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change within days of taking office, Trump froze permitting for all wind projects on federal land and oceans, accelerated the phase out of renewable power tax credits and pulled federal funding for low-carbon ventures like California’s hydrogen hub. Trump’s chosen path of what he terms “energy dominance” appears to be paved with fossil fuels.

Now, it’s the clean-energy industry’s turn to feel aggrieved.

Both parties need to “move beyond the idea that hydrocarbons and electrons have political affiliations,” Jason Grumet, CEO of the American Clean Power Association, said in March. In a message remarkably similar to Exxon’s CEO two years earlier, he continued: “It is time to join together behind a true all-of-the-above energy strategy.”

The phrase entered the energy-politics lexicon 25 years ago when a lawmaker in the House of Representatives, New York’s Benjamin Gilman, called on President Bill Clinton to boost domestic energy production at a time when supplies were dwindling. The country would need coal, oil, natural gas, wind, solar, hydroelectric, geothermal and biomass to reduce dependence on foreign imports, he argued.

“An effective national energy policy must, at a minimum, allow for all of the above,” Gilman said, citing a stance shared by American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry lobby group.

The same maximalist approach informed Bush’s Energy Policy Act of 2005, which included tax incentives for domestic oil and gas production as well as renewable fuels and wind and solar power. With US oil production at the lowest in decades, a primary concern for Bush was to reduce dependence on OPEC, which then had a seemingly impenetrable stranglehold on global crude supply.

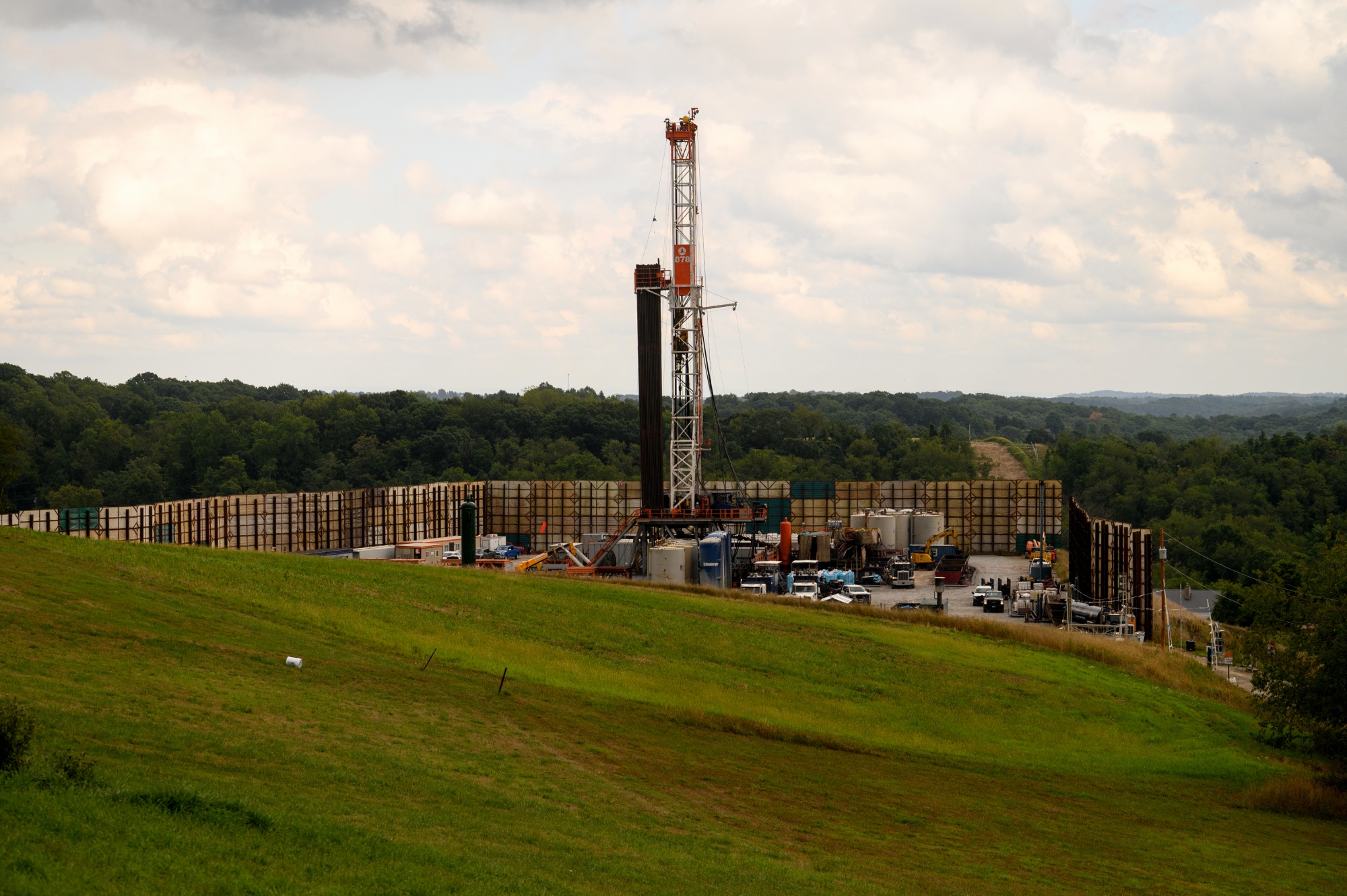

The policy proved more effective than even Bush could have foreseen. The incentives helped usher in fracking, a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing that turned America into the world’s largest oil producer and biggest liquified natural gas exporter by 2024. At the same time, federal policy also boosted ethanol, a fuel derived from plants that now typically makes up 10% of retail gasoline, and helped spark two decades of growth in wind and solar power generation. That eclectic orientation allowed renewables to emerge as an economically viable alternative to fossil fuels.

In a rare moment of bipartisan consensus, President Barack Obama became an unlikely champion of the policy. At the end of his first term, he was geared up for re-election with oil trading for more than $100 a barrel and gasoline prices surging. “This country needs an all-out, all-of-the-above strategy that develops every available source of American energy,” he said at the State of the Union address in 2012.

Oil, gas, wind and solar all surged under Obama’s watch, even though critics in the fossil fuel industry often chided him as being in hock to the green movement. In 2015, the year his administration signed the Paris Agreement, Obama also passed a law allowing US oil companies to export crude overseas, a critical provision that allowed fracking to flourish.

After Trump’s first election in 2016, and as the climate crisis became more urgent, many Democrats became convinced the only way to reach net zero by 2050 was to end all-of-the above politics and phase out fossil fuels. Biden, who entered the White House in 2020, made a clear move away from inclusive energy politics by canceling a permit for the Keystone XL pipeline in the first few days of his term. That set the stage for a years-long adversarial relationship with the fossil fuel industry, even as US oil production surged.

When gasoline prices and inflation soared after the pandemic, Republicans hit Biden relentlessly with accusations that his anti-fossil fuel policies were hurting ordinary Americans. In a typical attack from 2023, Republican Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming said Biden and Democrats “seem happy to surrender America’s energy advantage.” His solution: “We need to return to a pro-America, all-of-the-above energy strategy.”

Barrasso was understandably enthused when Trump won the 2024 presidential election and nominated Chris Wright as energy secretary, identifying the former fracking CEO as someone who would be committed to an all-of-the-above energy policy.”

But as Trump’s crusade against renewable energy gathered momentum, Wright made a surprise declaration.

“I have never been for all of the above, Wright testified in June. “And if I said it at one point in time I misspoke,” he said. “I am against energy sources that make the energy system more expensive or less reliable.”

The Trump administration plans to terminate funding for 223 energy projects amounting to $7.6 billion. While supporters may claim taxpayer dollars should not support such projects, Trump has also threatened or blocked about 8 gigawatts of power capacity, equivalent to 8 nuclear reactors.

Big Oil executives have largely praised Trump’s backing of fossil fuels, despite their years-long support for all of the above. It was Biden, not Trump, who began politicizing energy sources, they argue.

“The current president is a believer in American energy abundance as a source of economic strength and national security,” Chevron CEO Mike Wirth said at the WSJ CEO Council Summit on Dec. 9. “He’s actually a supporter, really, of all energy.”

Wirth then paused for a moment: “He’s not a big fan of wind, I guess.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.