Wild Power Swings Are Driving Australia’s Battery Boom

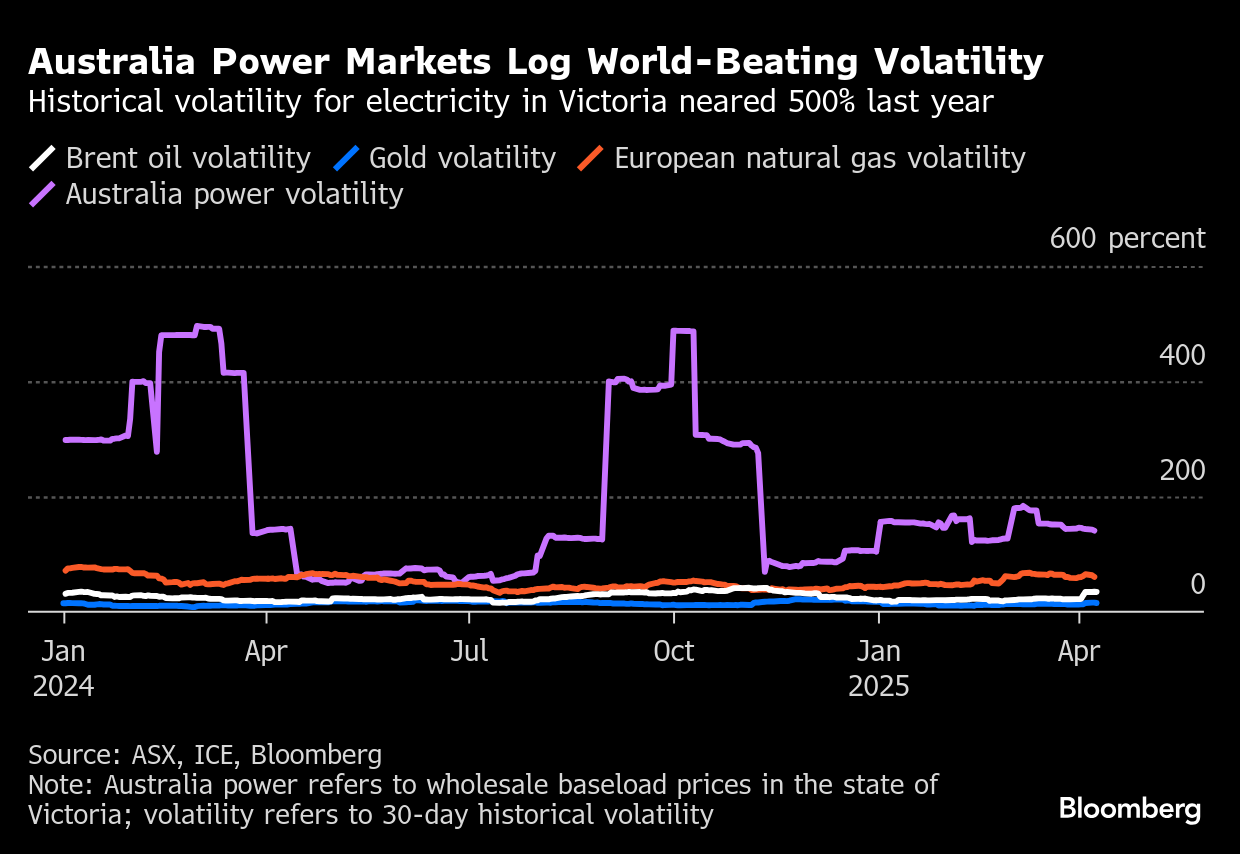

(Bloomberg) -- Battery investors are piling into Australia, chasing profits from the world’s most volatile power market by deploying storage that buys low and sells high.

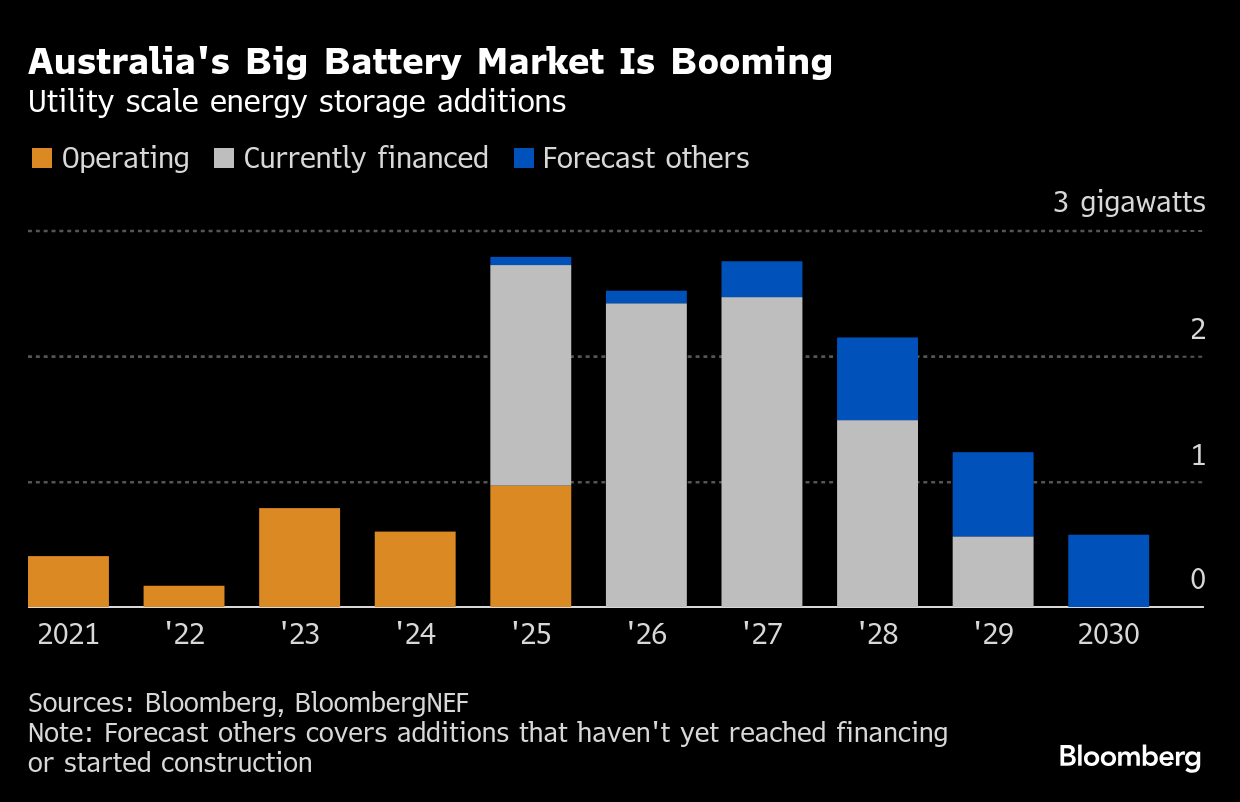

Australia this month overtook the UK to become the world’s third-largest market for big batteries by installed capacity, after the US and China, according to Rystad Energy. That growth is set to continue, with utility-scale battery power uptake expected to jump eightfold from 2024 levels by 2035, when most of the coal plants that form the backbone of the grid are set to retire, according to BloombergNEF.

The nation of almost 28 million is phasing out aging coal plants and aims to more than double renewable generation to 82% of the total by 2030, making it a test case for the global energy transition. A rooftop solar boom has aided the shift but also created midday power gluts, giving big batteries the chance to buy electricity cheaply and sell it back when prices rebound.

“Australia has a unique situation — or maybe you could call it a challenge — where all this surplus energy spills into the market every day,” said David Guiver, vice president and general manager of trading at the local unit of Shell Plc, which has stakes in several big batteries. “That why we have seen a lot of large scale battery energy storage investment.”

Large amounts of solar coming online, and frequent breakdowns at coal plants, have created an imbalance between supply and demand — even causing an unprecedented market failure in 2022. Prices are often negative around midday — meaning users are paid to consume electricity — and soar during peak demand hours in the early evening, providing arbitrage opportunities.

Australia is the latest market where energy traders are betting on batteries to pad profits. After making fortunes hauling oil, gas and metals around the world, trading houses in Europe including Vitol Group and Trafigura Group have been turning their attention to opportunities to store and sell energy back to the grid. In the US, batteries have helped to prevent blackouts, although their rapid rollout has been hampered as tariffs add to costs.

Electricity prices in Australia’s main grid were negative or zero during a record 23% of the grid’s five-minute intervals in the fourth quarter of last year, which includes most of the southern hemisphere spring. That number fell to almost 11% in the first quarter, but is still above the rates seen in most European markets.

Last year, A$3.7 billion ($2.4 billion) was committed to large-scale battery projects in Australia, following a record A$6.9 billion in 2023, according to the Clean Energy Council. Meanwhile, rooftop solar installations were the most since 2021 — despite one in three homes already having panels, the highest penetration globally.

“Volatility is a massive opportunity that’s highly undervalued by the market,” said Nick Carter, chief executive officer of Akaysha Energy, a Blackrock Inc. unit that has battery projects in Australia, Japan and the US. That spread will likely hold or even widen over the next five to 10 years, he said.

Utility-scale batteries connected to the National Energy Market earned A$120.8 million in revenue from arbitrage last quarter — more than quadruple their income a year earlier. Batteries set prices in the grid 8% of the time, and were the highest-cost source at more than triple that of hydro, the most frequent price-setter.

That is a relatively new phenomenon — battery owners used to get most of their revenue by being paid to help balance demand and supply in the grid, known as ancillary services. However, the business model and technology have evolved rapidly since Elon Musk’s successful bet in 2017 that he could get the world’s first 100-megawatt model up and running in 100 days to help prevent outages in South Australia.

“Arbitrage is replacing ancillary services as the primary revenue stream for batteries, which we anticipate to remain the case,” said Andrew Stiel, head of energy markets at Edify Energy Pty, a renewables and storage company. “This is the new normal.”

Akaysha, which doesn’t own power-generation assets or have retail customers, looks to arbitrage or government contracts for revenue. The company earlier this month started an A$1 billion super battery that’s set to be one of the world’s biggest at more than eight times the size of the original one Tesla Inc. helped build.

However, for traditional power utilities such as AGL Energy Ltd. and Origin Energy Ltd., batteries also serve as a means of limiting financial losses. They help manage portfolio risk due to outages, coal plant retirements and increasing price swings.

Origin has committed about A$1.7 billion to developing two utility-scale batteries and has secured offtake agreements for two more that are under construction. Meanwhile, AGL — Australia’s biggest coal generator — operates two grid-scale batteries and expects to start a third early next year.

“Batteries have solved the need for short duration storage and quick response capacity,” said Simon Sarafian, general manager trading and origination at AGL. “We’ve been very happy with how our batteries have been performing, and we’re looking to roll out more.”

Earnings from the units will more than offset higher coal and gas procurement costs from 2028, AGL Chief Executive Officer Damien Nicks said during the company’s half-year earnings presentation on Wednesday.

“So many batteries and so much capacity needs to be built in this market,” he said. “Don’t underestimate the sheer amount of batteries that are required in this market over the coming decade. It is enormous.”

(Corrects spelling of Stiel’s name in 12th paragraph. A previous version corrected Edify Energy’s ownership.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.