Looking for a Cooler Commute to Work? Try Anywhere With AC

(Bloomberg) -- Commuters crammed inside hot and clammy underground trains into London’s financial center over the last few months may be wondering what life could be like working in another city.

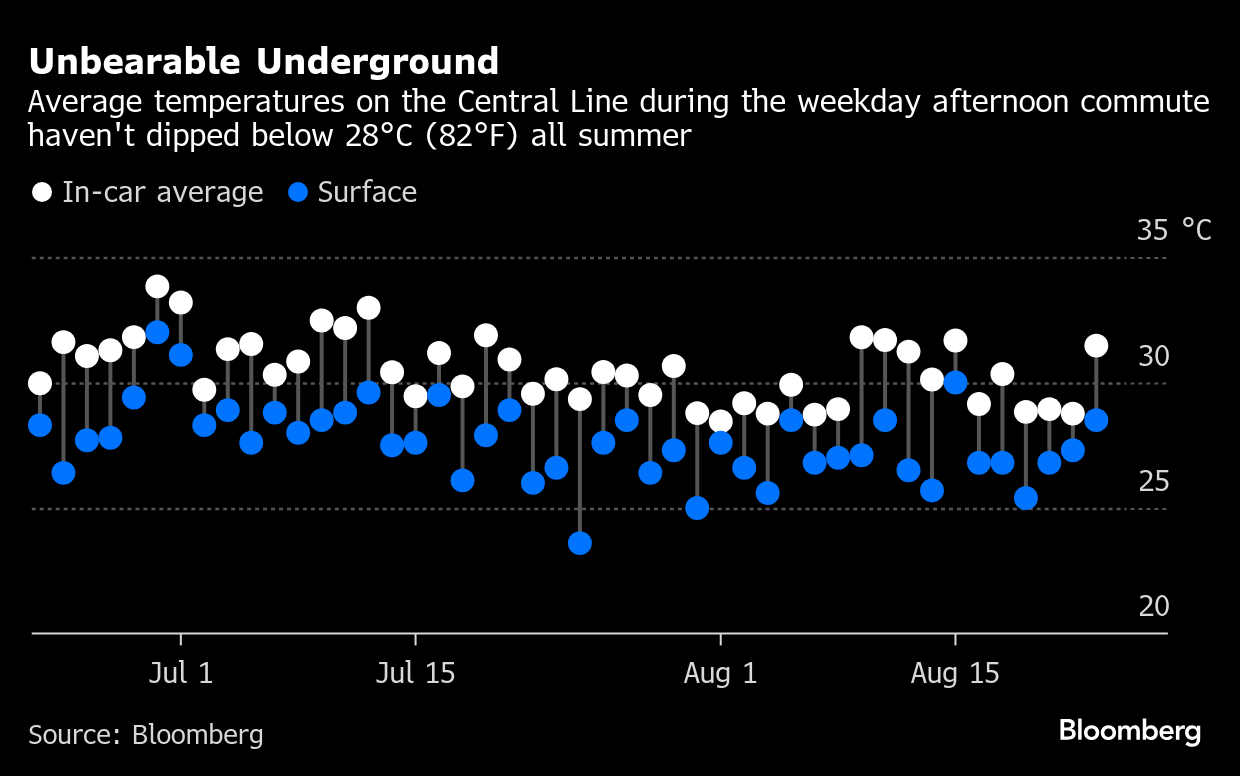

While climate change is raising temperatures everywhere, cities like Beijing or New York offer more air conditioned transportation systems capable of keeping their commuters cool. Passengers on London’s busy Central line, for one, have endured heat wave conditions underground every day this summer, according to data recorded by Bloomberg.

The line’s deep, narrow tunnels trap heat from the surface as well as train car brakes on the rails. As first reported by Bloomberg News in June, temperatures inside the uncooled tube carriages can climb 5C (9F) above the surface.

Using an Aranet4 sensor, Bloomberg has since June 23 been tracking temperatures on the Central line from Bank station in the financial district to Bond Street in the posh Mayfair neighborhood.

While air conditioning is available on some parts of London’s vast transportation network, Transport for London officials say there’s no easy fix for the oldest, deepest reaches of a system that move through century-old tunnels beneath the densest parts of the city.

With the UK Met Office calling this summer “almost certainly” the warmest on record for the country, we took a look at how subway systems in four other big cities — Tokyo, New York, Beijing, and Paris — have been equipped to deal with heat. Some of the findings may give Londoners a few reasons to feel jealous.

The sweltering summer months make commuting into Tokyo an uncomfortable routine for many, but passengers can count on air conditioned stations, platforms and carriages.

Tokyo Metro Co., one of the operators of the city’s subway lines, has equipped all of its 159 underground stations with air conditioning, according to a spokesperson.

Many companies have adopted a no-ties and jacketless “cool biz” dress code for the summer, which helps lessen some discomfort for employees enduring hour-plus train rides into work. Passengers enhance this look with fans and ring-shaped ice packs around their necks.

Transport officials in Tokyo started installing air conditioning in the 1970s as the city rapidly urbanized and the heat and humidity in train cars started to rise. Temperature at Ginza Station, located in Tokyo’s major shopping district, touched 33C (91F) in August 1970, but dropped to 24C after cooling was installed, Tokyo Metro records show.

Extreme temperatures raise alarm bells at Odakyu Electric Railway Co., one of the railway companies that operate lines in the suburbs of Tokyo. If a rail temperature reaches 45C, staff are dispatched to ride trains and conduct inspections.

Air conditioning is so prevalent in Tokyo’s subway system, that recent cooling failures at Tokyo Metro’s Kasumigaseki and Hibiya stations — both in the heart of Japan’s government ministries and agencies — topped local news headlines.

In New York City, subway carriages are air-conditioned, but most platforms usually aren’t. In the summer, hot exhaust from the train car cooling systems, combined with braking heat, vents onto passengers waiting to board.

On a recent afternoon in August, Bloomberg tracked temperatures above and below ground in New York with the same type of sensor used in London. The readings showed temperatures near City Hall in downtown Manhattan hovered around 33C. Underneath the street, the heat skyrocketed to 37C on the subway platform and felt closer to 42C with humidity — nearly 10C hotter than the surface. Once inside an air-conditioned subway car, the temperature still measured 32C, as cold air escaped and hot air rushed in during its stops.

Passengers whipped out battery-powered plastic fans — or resorted to fanning themselves with whatever envelope or piece of mail they had on hand. At Times Square, a cluster of graduate students from Touro University shifted uncomfortably as they waited on a packed platform for an uptown express train.

Despite the day’s sweltering temperatures, Lucinda, a pharmacy student who declined to give her last name, wore a long-sleeved blouse and pants. “The classrooms are cold,” she said.

Subway malfunctions and outages this summer have left passengers stranded below ground and scrambling to reroute their trips. Mike Ardito, who works in retail near Manhattan’s Herald Square, said he now stashes an extra shirt at his office in case he hits a snag on his daily commute from Astoria, Queens.

“If you’re not lucky, you start your day at work already sweating,” Ardito said. “And it’s not the best. You don’t smell like a flower.”

Looking ahead, New York’s transportation authority says it expects the number of days above 32C to triple by the 2050s. Extreme heat raises the risk of equipment failures, which can cause delays to rack up throughout the system. To cut the heat, officials are exploring up to $250 million in upgrades, including added ventilation in subway tunnels and overhead fans to help with air circulation in steamy stations.

In Beijing, hour-long commutes on one of the world’s longest subway systems are common — and summers are getting hotter and more humid.

Efforts to keep passengers cool have largely been successful. The network started operating in 1969, which is relatively new compared to subway systems in the Western Hemisphere. Underground platforms are air-conditioned, while above-ground stations are cooled by fans and water misters.

Subway carriages are air-conditioned and equipped with sensors that pump in cooler air when cars get crowded. Beijing’s subway also has carriages with two temperature ranges from cold to cool. “Cold” cars cater to executives trying not to sweat through wool suits and have temperatures on average about 2C (3.6F) below “cool” cars, which are more comfortable for everyday travelers dressed in tank tops and shorts.

While London holds the title for the world’s first underground passenger railway, opening in 1863, Paris’ system shares almost the same amount of history. The first line in the French capital’s network was inaugurated at the turn of the last century to connect the various sites of the World Fair and serve the summer Olympic Games in 1900.

Subsequently, Paris faces many of the same challenges as London in providing cooling upgrades. Most Paris metro lines can’t accommodate full air conditioning due to narrow tunnels that trap hot air, and increased risks of service disruptions from overheating equipment.

Government authority Île-de-France Mobilités is spending more than €3 billion a year over a decade to modernize, automate, decarbonize and expand the metro system in Paris. The city hosts an annual 50 million tourists, on top of the locals who use the metro.

Where air conditioning is not possible, transportation authorities have been deploying cooled ventilation, which is a mechanical system that can lower temperature by a few degrees inside the trains to give passengers a sensation of freshness while being less energy-intensive.

Today, half of the metro trams in the Paris region are equipped with cooled ventilation, with a plan to roll the system over the entire fleet by 2035, Île-de-France Mobilités said in a statement in June. Two-thirds of trains and regional express network (RER) lines in the area feature either air conditioning or cooled ventilation, while all tramways are already fully air-conditioned. Nearly 60% of buses and coaches are now equipped with air conditioning.

Many metro stations are also now cooled with ventilation and fans, which were part of major upgrades ahead of the Olympic games last year.

Île-de-France Mobilités has installed 136 water fountains across the transport network since the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games last year, giving commuters greater access to drinking water during extreme heat. An interactive page on the company’s website, maps places in Paris and its surrounding areas where people can have access to nearby cooling shelters and drinking water fountains.

The sweaty summers aren’t just affecting Paris commuters: While trains are increasingly automated, many are still operated by drivers who work long hours underground in sweltering, humid conditions. RATP Group, which operates the Paris metro and other public transport systems, has distributed to drivers jackets made from fabric that soaks up perspiration and cools wearers as the sweat evaporates.

During heat waves this summer, the Paris’ transport authority handed out water to passengers. But most Parisian subway-goers kept their cool using the same strategies their London counterparts employ: sweat, fans — and fever dreams of chilled drinks at the bar.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.