China Is Running the World's Most Powerful Floating Wind Turbine

(Bloomberg) -- Off the coast of southern China, a giant, double-headed turbine rises out from among its conventional counterparts, held up by a spiderweb of steel cables and tethered to the seabed below via three bright-yellow mooring points.

The OceanX design pushes the boundaries of engineering, able to harness more wind power than any other floating turbine operating in the world today. It’s also an eloquent symbol of the ambitions of Chinese green technology companies, securing their dominance of yet another clean-energy industry as stalwarts in Europe, the US and Japan run up against political and economic setbacks.

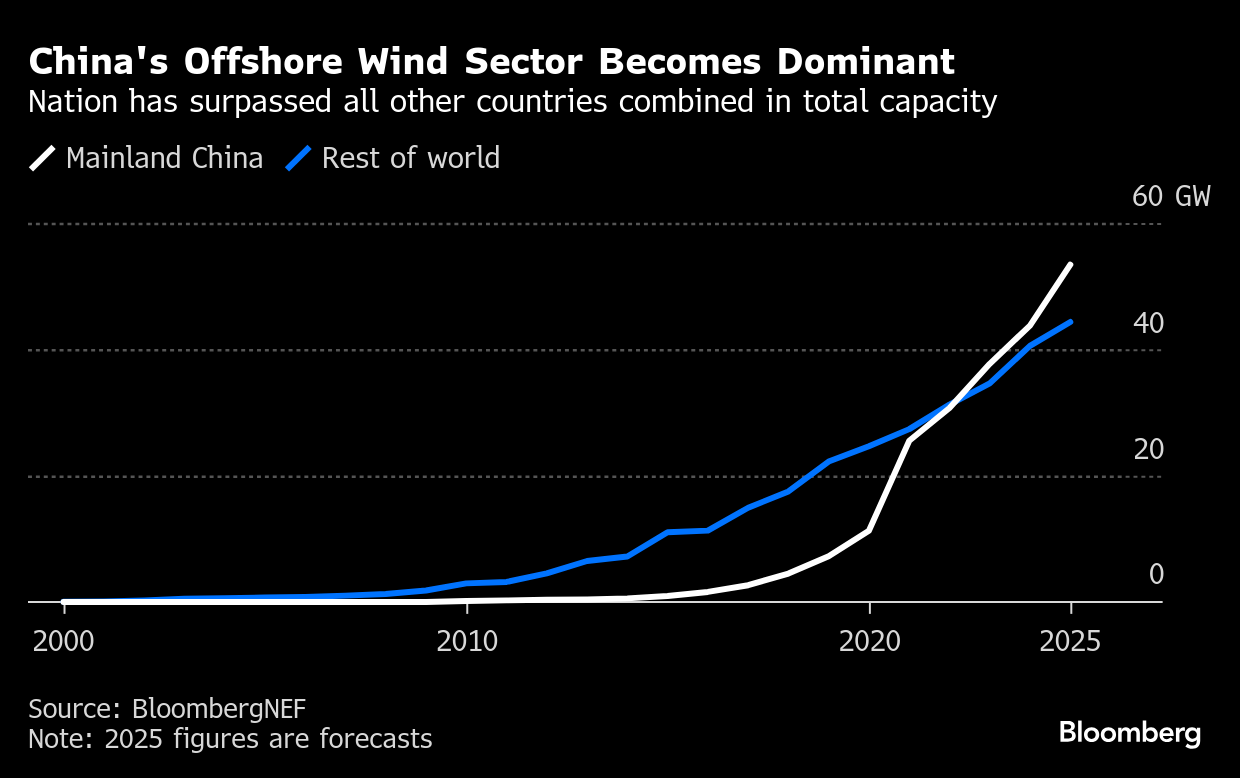

China, whose reliance on imports means energy security is always front of mind, has led the world when it comes to using renewable electricity sources — that includes expansive solar farms in western deserts but also rows of turbines built at sea, where they can access reliable and stronger air currents. This year, it will install nearly three out of every four of the world’s new offshore turbines, according to BloombergNEF.

The story is very different elsewhere, particularly in the US, where President Donald Trump has derided wind farms as ugly killers of birds and whales. He targeted wind on his first day in office, halting approvals for new offshore ventures. His administration stopped an almost-complete project, rattling investors and triggering a collapse in the share price of its Danish developer, Orsted A/S, a company that has led the sector for more than three decades since it commissioned the world’s first offshore wind farm.

Now along with other operators in Europe, the US and Japan, Orsted is struggling to cope with dwindling government support and costs that continue to push upward, thanks to pricier components, high interest rates and limited infrastructure.

Mitsubishi Corp. dealt the latest blow on Wednesday, saying a group it led would withdraw from three offshore wind projects in Japan, citing tighter supply chains and rising costs since the tender was secured in 2021.

“China’s offshore wind project pipeline has remained strong because of advantages in financing, supply chain integration, policy support and technology improvements,” said Yujia Han, a Washington-based researcher for Global Energy Monitor. “You have this playground of a big and diverse market that provides all those domestic companies with a platform of skills and innovation needed to build their global competitiveness.”

China’s largest players are seizing the opportunity. Turbine makers including Goldwind Science & Technology Co. and Ming Yang Smart Energy Group, which built OceanX, are increasingly looking to compete internationally — taking on industry stalwarts such as Vestas Wind Systems A/S, Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy SA and General Electric Co.

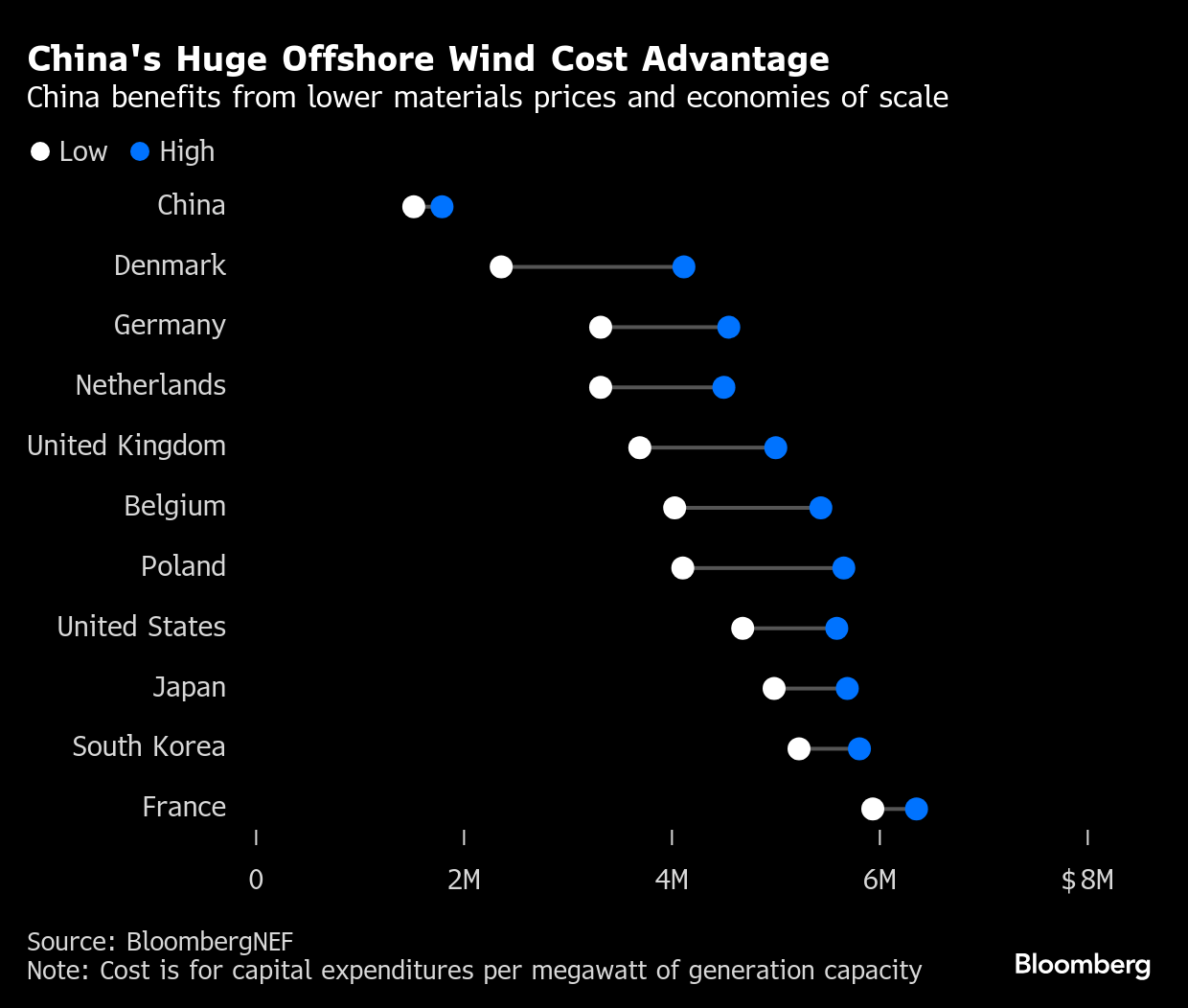

“Chinese manufacturers are going to take most of the market share because of their fundamentally huge advantages in cost — and also just the enormous difficulties a lot of the Western firms are facing at the moment,” said Cosimo Ries, an energy analyst with Trivium China. “It will make it very, very difficult for them to expand capacity and invest in the way Chinese firms are doing.”

Even in the European heartland that nurtured the industry after the 1970s oil crisis, offshore wind projects are falling out of favor. Scotland may have signed off on what could be the world’s biggest site, but an auction in Germany this month ended without a single bid, as prices rise.

The problems sound all too familiar to the Chinese manufacturers that have survived domestic upheaval and cut-throat competition. At the end of 2021, the government phased out national feed-in tariffs, which guaranteed premium rates, leading to record-breaking installations that year before they dropped sharply after.

They have also been forced to go ever deeper out to sea, as the number of prime near-shore sites shrinks. In some areas, that’s pushed developers up against military restrictions.

It’s to counter those challenges, especially the end of national subsidies, that developers have turned to scale, meaning ever larger projects and even bigger turbines. The result has been clean energy for China’s coastal cities, and a sharp drop in prices. The median cost of offshore wind power in China is now less than half that of the UK, the second-biggest market, according to BNEF data.

Still, replicating that advantage overseas hasn’t been as straightforward as it has for other new-energy sectors where China dominates, including solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles — and the main hurdle is that gargantuan size. These wind turbines can eclipse the Eiffel Tower, meaning that assembly is more like a construction project than traditional manufacturing, with much of the work needing to be done close to the final installation sites.

At one factory owned by Ming Yang in the fishing town of Yangjiang, 250 kilometers west of Hong Kong, the scale is evident. On an early August morning, dozens of workers walked across a curved platform resembling a giant surfboard more than 100 meters long, soon to be assembled into a wind turbine blade.

“We were among the first major companies to establish operations here,” said Ma Liming, Ming Yang’s general manager of the facility. “Since then, over 30 upstream and downstream suppliers in the wind power sector have followed.”

Currently, about 15% of the plant’s output goes to overseas markets such as Italy. That share is set to almost double by year-end, Ma said.

For the moment, Yangjiang’s turbines mainly supply vast wind farms off Guangdong, one of China’s most economically vibrant provinces and a major electricity consumer. The province wants to build 17 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2025 — more than any single country apart from China has built to date.

The area’s geology — a seabed of soft clay on top of hard rock that is tricky to drill into — has favored supersized structures as developers try to keep costs in check. Turbines here are about 20% bigger than the national average.

But these mammoth Chinese-made machines have not seen rapid adoption elsewhere, in part because of a limited operational track record that means foreign developers, insurers, and financiers are less eager to jump on board, especially in regions like Europe, with established, existing players.

“It’s a big difference from before,” Zhang Qiying, president of Ming Yang’s international business, said in an interview at the company’s headquarters in Zhongshan. “We have talked with a lot of Western developers now, because we have more innovative products and technology.”

So far just one offshore site in Europe — the Taranto project in southern Italy — uses Chinese turbines. Meanwhile, a wind farm in Germany sought to cancel its order with Ming Yang, after the deal prompted scrutiny from the German government and warnings from Europe’s wind industry around national security and unfair competition.

Ming Yang confirmed that it was no longer involved in the German project, but says it remains committed to the European market and is exploring opportunities including local production.

The key, says Zhang, is to convince European governments and engineering firms that Chinese companies will be around to provide good service and maintenance for the next 25 or 30 years, and can make efforts such as building local teams. In the meantime, the European market also needs to change their perspective of Chinese makers, he said, welcoming new and more innovative products.

“I’m sure that will happen — it’s cleaner and cheaper offshore wind power,” he said. “But you can’t do that with barriers.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.