Floating Solar Panels Turn Old Industrial Sites Into Green Energy Goldmines

(Bloomberg) -- Putting solar panels on water to generate power sounded like a dangerous gimmick to Benedikt Ortmann when he first heard about the idea.

“Every child knows electricity and water don’t mix,” said Ortmann, the top solar executive at Munich’s Baywa r.e., one of Europe’s biggest renewable energy developers.

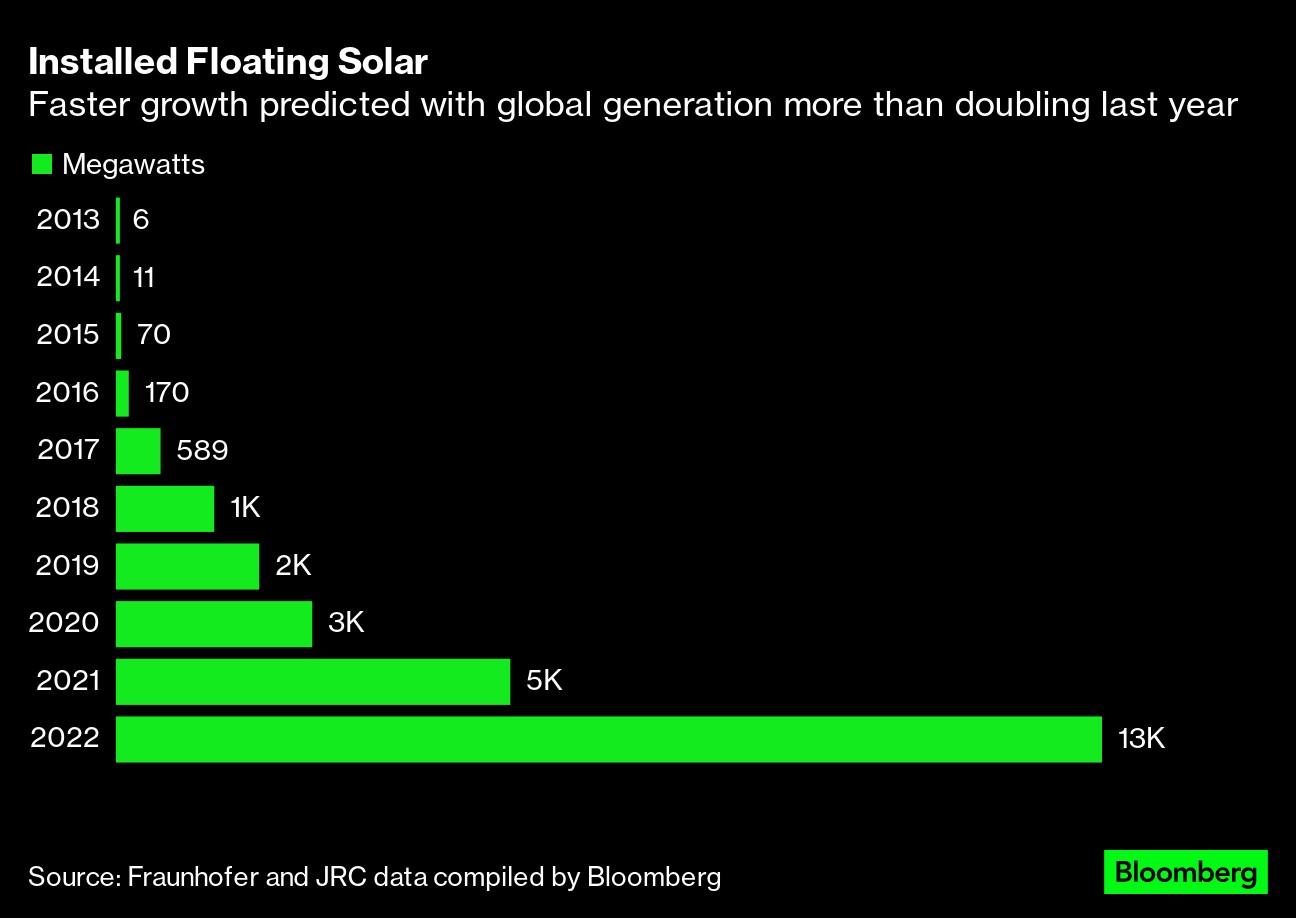

When Ortmann installed his first array of floating panels back in 2018, Baywa r.e.’s business was mostly made up of traditional ground-mounted solar. But five years later, the company is now Europe’s leading producer of floating photovoltaics, otherwise known as FPVs, or “floatovoltaics” in industry parlance. While floating solar represented less than 1% of all panels installed globally last year, their use has grown more than 2,000% in the last decade.

And increasingly, they’re being installed on bodies of water in former coal pits and stone quarries, and in hydropower lagoons.

One driving factor behind this shift is the explosive uptake of solar panels on European rooftops over the past two decades, which has put pressure on finding new real estate for renewables. Subsequent efforts to build in rural areas have been complicated by pushback from farmers and locals upset at the prospect of panels spoiling their views. “Agriculture still sees solar panels as a threat that competes for the same land,” said Matthias Taft, chief executive officer of Baywa r.e.

Floatovoltaics sidestep this issue, and are able to breathe life into sites that have fallen into neglect. “Most of these former gravel and sand pits aren’t used anymore. They’re low-hanging fruit,” Taft said.

Baywa r.e. has already installed floating panels capable of generating half a gigawatt of energy in Europe and Asia, and is assessing new sites in South America. Its overall project pipeline currently stands at 28 gigawatts — a peak output equivalent to a few dozen nuclear reactors — which the company expects will triple by 2025.

To meet mounting demand for FPVs, European governments, businesses, and utilities are scouring out-of-use industrial areas for available bodies of water. At the top of the list are ponds and lakes that don’t attract many visitors, and which have steady water levels that won’t disappear beneath snow pack in winter.

Access to infrastructure and proximity to population centers are also essential. “Right now, the main constraint for solar build in Europe is a shortage of places with an easy grid connection and land permits,” said BloombergNEF solar analyst Jenny Chase.

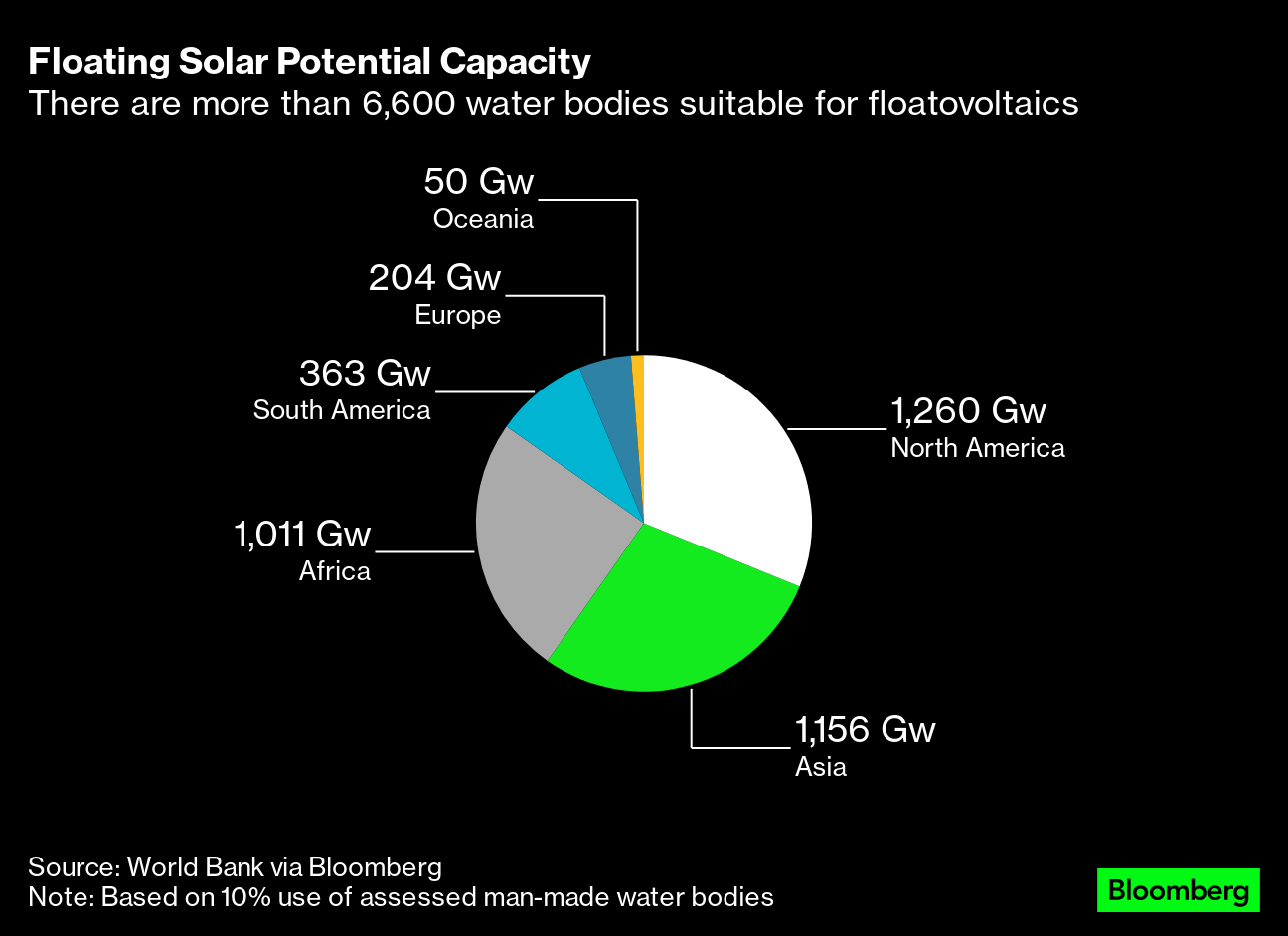

The World Bank figures that Europe could cover at least 7% of its annual power consumption by deploying floating solar panels on just 10% of artificial lake surfaces. If this were scaled globally, the amount of electricity generated would rise to 5,211 terrawatt hours a year — more than all the electricity consumed annually by the US, the world’s largest economy.

Austria, home to central Europe’s biggest floatovoltaic array, has rolled out special subsidies for floating PVs and other novel projects that combine electricity generation with an ecological or agricultural aim. Scientific studies show that FPVs improve water quality by reducing algal blooms. Panels can also help save water during times of drought by reducing evaporation and decreasing sunlight penetration.

Small countries “have to be smart” when it comes to innovative solutions for clean energy generation, said Leonore Gewessler, Austria’s climate and energy minister. The Netherlands has installed the most floating solar capacity in Europe, and interest is picking up in Italy, Portugal, Switzerland and the UK.

Austria’s first floating power plant in Grafenwoerth, an hour’s drive west of Vienna, is one example of what a green future might look like. Surrounded by farmland and situated next to a sand and gravel business, the former quarry was developed by Baywa r.e., local utility EVN AG and municipal authorities. After two years of planning, workers needed just two months to install the 24.5 megawatt-capacity panels, and the site went online in February.

Developers are also eyeing former coal mines in neighboring Germany, which could host up to 2.7 gigawatts of floating solar power, according to the Fraunhofer Institut. In May, German coal miner LEAG AG announced plans to install floatovoltaics on an artificial lake southeast of Berlin.

Old coal regions are “ideal” for this technology, said Dominique Guillou of EP New Energies GmbH, who is overseeing the effort to transform the Cottbuser Ostsee, once a coal mining pit in a former hub of Germany’s fossil-fuel economy, into a green powerhouse with 29-megawatt capacity. When the project is finished in 2024, it’s expected to become Europe’s biggest floatovoltaic generator.

But even with FPV-generated power more than doubling each year, Baywa r.e. doesn’t expect the European floatovoltaic market to fully take off just yet. Red tape still abounds and environmental licensing assessments can take even longer than for land-mounted solar. Yet by 2025, the company predicts that regulators will have had time to familiarize themselves with the technology and will start approving more requests to install floating solar.

And once permits are granted, things tend to move fast. It took 50 workers just a day to install 1.5 megawatts of new energy capacity on the waters of a former quarry in Austria.

“There was a lot to learn the first time,” said Benedikt Kammerstaetter, who managed the project over its two-month installation.

“But now it’s just cut and paste. It becomes quicker and easier.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.