G-7 Energy Ministers Face Climate Fight With Japan as Host

(Bloomberg) -- As the world’s most advanced economies discuss tackling climate change in Japan this weekend, the host country is set to face some uncomfortable scrutiny of its policies to deliver on green targets.

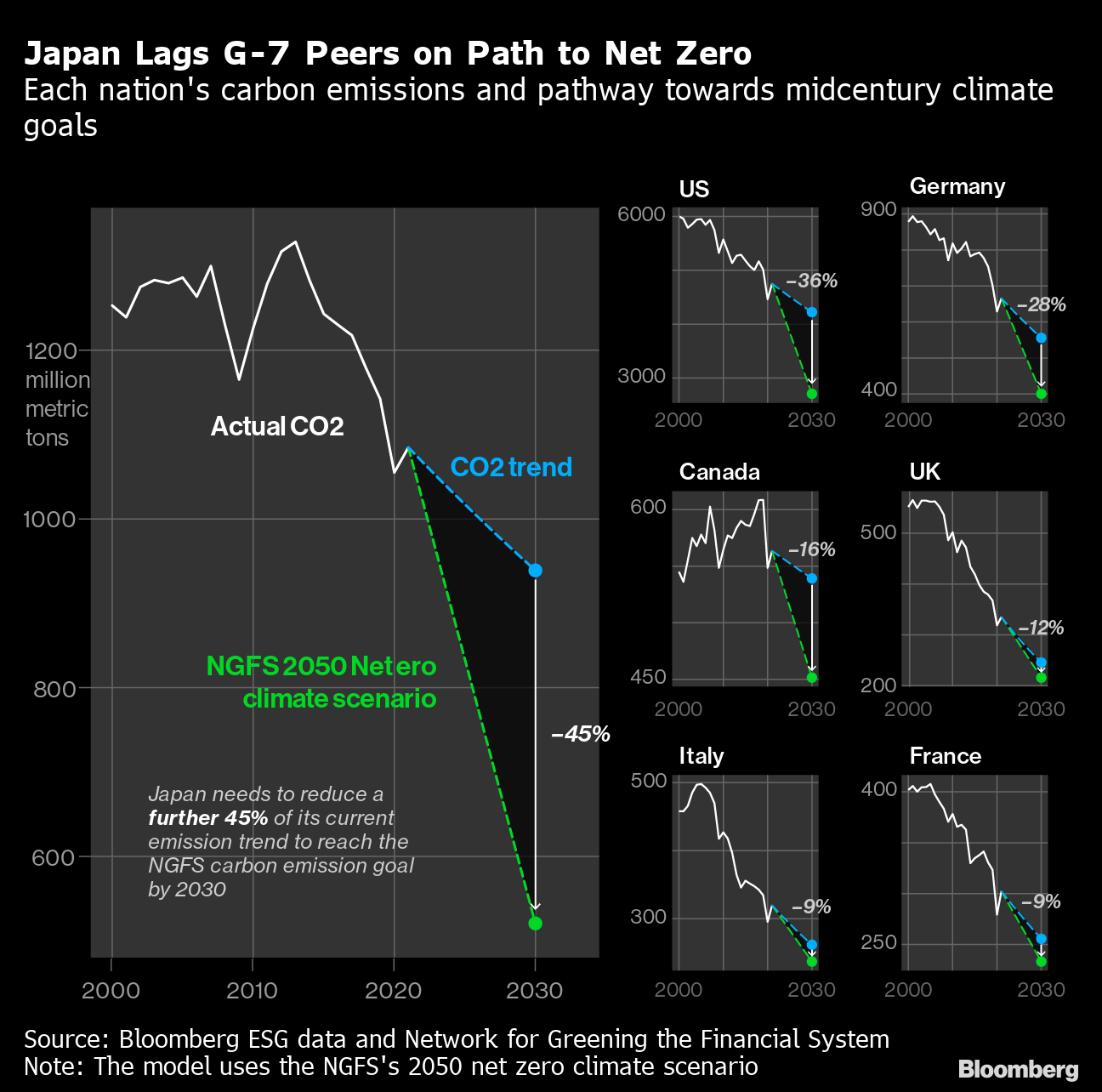

The Group of Seven have appointed themselves leaders in the global mission to decarbonize. But Japan’s plan to eliminate carbon pollution from its power sector is an outlier among its peers. Its current emissions-reduction trajectory strays the furthest from what’s needed by 2030 to reach net zero by 2050, according to data compiled by Bloomberg and the Network for Greening the Financial System, an organization of more than 100 central banks and regulators.

Despite their outsize contribution to the planet-warming carbon dioxide that’s accumulated in the atmosphere, no G-7 country has made pledges to the United Nations that are sufficient to keep the world from warming less than 1.5 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels, according to the nonprofit Climate Action Tracker. Even so, Japan stands out for its approach, which relies heavily on carbon capture, ammonia and hydrogen to keep burning fossil fuels.

Banking on these technologies for gas and coal-fired power plants “is a very, very dangerous play by the Japanese government,” said Maria Pastukhova, a senior policy advisor at the consultancy E3G. Their use as climate fixes “have not yet proven commercial and it is uncertain how scalable these solutions are, or how fast the cost can be reduced.”

The Asian nation’s reluctance to move away from carbon-intensive energy sources was reflected in draft communique documents circulated ahead of the G-7 energy and environment ministers summit in Sapporo. Japan, along with the EU and the US, expressed reservations about setting a 2030 deadline to phase out unabated domestic coal power. It's also pushed for language endorsing the use of hydrogen and ammonia as a power source, and been supportive of more gas investments.

Securing metals critical for building green technologies is also under discussion the NHK reported Friday, and G-7 members are working on a plan to allocate more than 1 trillion yen ($7.5 billion) toward the development of supply chains to ensure supplies of minerals like lithium and nickel. The proposal may help sidestep export restrictions by countries including China and India on raw materials critical for manufacturing batteries and building clean energy infrastructure.

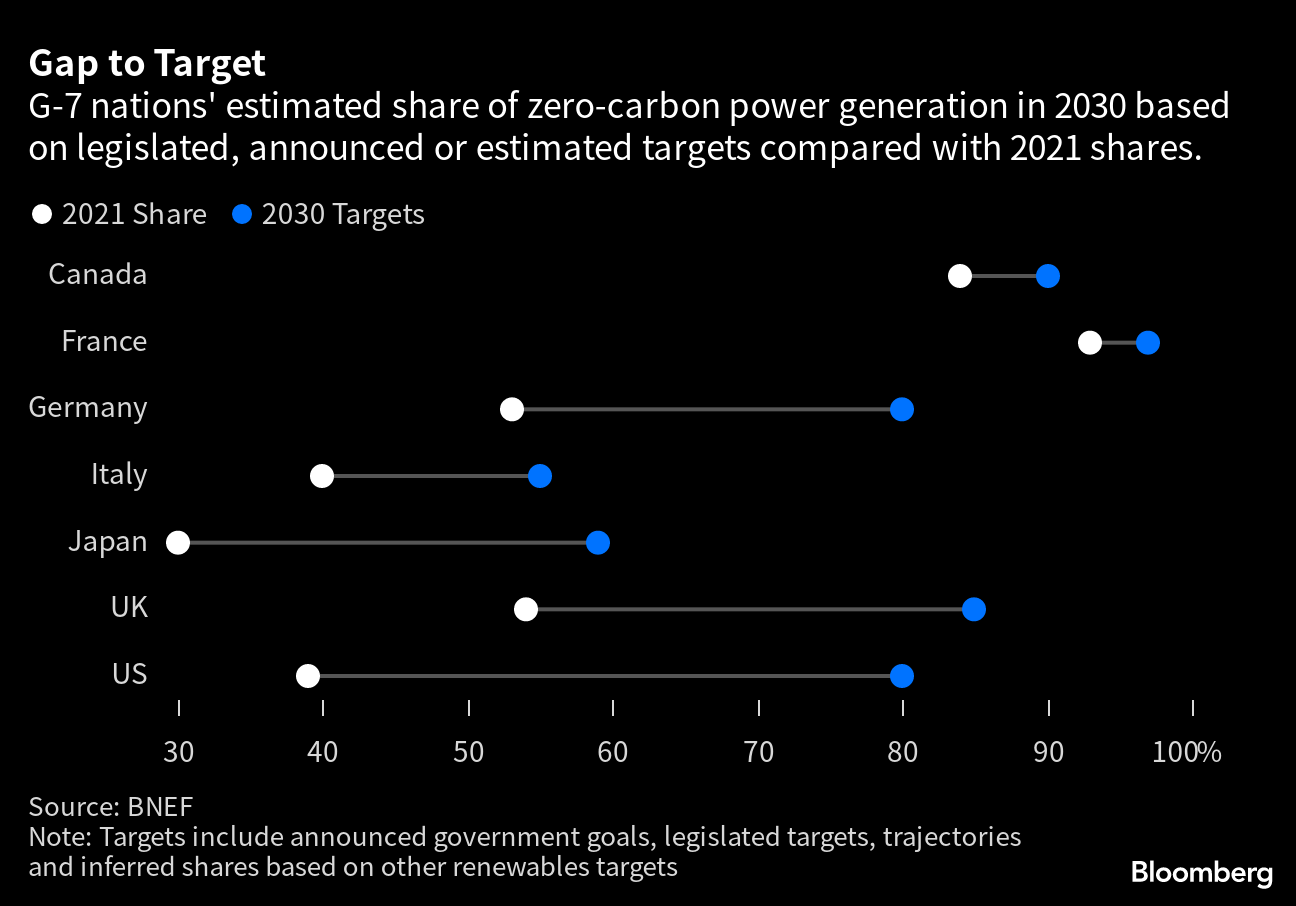

Japan had the lowest share of zero-carbon power generation — from solar, wind, hydro and nuclear — in the G-7 in 2021, according to an analysis by BloombergNEF, and is projected to have the second-lowest after Italy by the end of the decade. Current deployment of solar and wind power are nowhere near the rate needed to reach the government’s target of having renewables contribute 36% to 38% of power by 2030, according to Ali Izadi-Najafabadi, an analyst at the research group.

Research shows that prolonging dependency on fossil fuels will make it harder for countries to reach their net zero goals, especially since clean energy such as solar and wind is already cheaper than coal in many places. Doing so through the use of carbon capture, ammonia and hydrogen would also require a breakthrough in the technologies that makes them much cheaper and less energy-intensive than they are now.

Using carbon capture “for power generation is a bad idea economically, environmentally and socio-economically," said Matt Gray, chief executive officer of UK-based nonprofit TransitionZero. "Renewables, storage and grid upgrades are cheaper, cleaner and will create more jobs.”

BNEF predicts that ammonia will continue to be much more expensive than solar and wind even in 2050, and its climate benefits may be limited because burning the fuel can generate nitrous oxide, a super potent greenhouse gas. And while Japan has a number of pilot carbon capture projects, none of them are of commercial scale, according to the Global CCS Institute.

“It is not appropriate to criticize the government just because [it is] taking a different pathway from that of Europe, which places more emphasis on renewable energy,” Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry said in response to questions. Japan is not more reliant on carbon capture and storage (CCS) than the US and UK, which have pledged tens of billions of dollars of support for the technology, it said.

While many countries are banking on CCS to help curb emissions, much of the focus is on sectors such as steel and cement production where there are few carbon-free alternatives. Japan, however, intends to use them to keep coal and gas plants running for decades. Even if the government hits its target of developing facilities capable of capturing 240 million tons per year by midcentury, that would only eliminate the equivalent of roughly a quarter of its 2020 emissions, according to BNEF.

While Japan has limited land space for giant onshore wind and solar farms — about three fourths of its land is mountainous — there are millions of square meters of industrial and commercial rooftops where panels could sit, according to Doug Deeks, chief operating office at Solar Power Network, an Ontario-based PV developer active in Japan. Disused agricultural land could also be an option, he said.

Japan has proposed a new type of sovereign debt, known as GX bond, with 20 trillion yen ($143 billion) of government support over 10 years, to meet its goal of cutting emissions 46% by 2030. That could potentially help it catch up with aggressive policies already in place in other G-7 countries, such as the US’s $374 billion Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s carbon market. The Japanese government is still in the process of developing a framework for the instrument, METI said.

The nation is also working toward meeting a target for all new passenger car sales to be electric vehicles by 2035, though policies mandating the long-term phaseout of internal combustion engine vehicles have faced pushback from Toyota Motor Corp., according to nonprofit think tank InfluenceMap. The company said it is “sincerely working” on carbon-neutrality issues. Meanwhile, Japan’s EV adoption is forecast by BNEF to be the lowest among G-7 countries by the end of the decade.

Meanwhile, Japan needs a more modern power grid that can more easily accept renewable power and distribute those electrons where they are required. The country estimates it will spend between 3.6 and 5.4 trillion yen ($27 and $41 billion) through midcentury to boost interregional transmission, according to an analysis of the plan from BNEF. While this will help move clean electricity from southern regions with lots of sunshine and potential offshore wind sites in the north to more central demand corridors, the government still envisions renewables only making up around half 50% of the nation’s power generation by 2050.

The investment is significantly below what is needed to ensure the grid is capable of meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals, according to BNEF, which estimates Japan needs at least 86% of its energy generation to be clean, requiring an expenditure of $56 billion for interregional grid transmission. Much of the disparity boils down to new grid connections, because policy makers plan to keep as much as 143 gigawatts of fossil fuel plants online by midcentury, according to BNEF. That compares with the researcher’s net zero scenario, which sees Japan only having 52 gigawatts of fossil fuel capacity by 2050.

"Unless there is a drastic, immediate shift in policy,” said BNEF’s Izadi-Najafabadi, “Japan will continue to lag its G-7 peers.”

(Updates with proposal to help secure critical metal supplies in sixth paragraph.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.