How a Flawed But Historic Climate Deal Emerged From COP Chaos

(Bloomberg) -- Hours after the COP27 climate talks reached the deadline, there was still no deal and the European Union’s climate chief was threatening to leave Sharm El-Sheikh without one. “We don’t want a result at any price,” Frans Timmermans told reporters, flanked by ministers from Germany, Austria, Ireland and Spain. “The EU would rather have no decision than a bad decision.”

The annual United Nations climate summit has only ended once without a major agreement, and in recent years, as the impacts of climate change have become more devastating, the meetings have taken on increased urgency. In the 24 hours after Timmermans and the EU raised the prospect of a no-deal outcome in Egypt, delegates from nearly 200 countries barely managed to avoid a stalemate.

Ultimately the Europeans and their allies accepted the kind of flawed outcome they had vowed to avoid. The COP27 summit adopted an accord that doesn’t increase ambitions on lowering emissions or take new steps to preserve the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit for warming temperatures. It also commits to the creation a loss-and-damage fund that, if details can be worked out at future talks, will send aid to vulnerable countries wrecked by the irreversible harms of global warming. That stands as an enormous achievement — a deal three decades in the making that many doubted would come from this year’s meeting.

Read More: A Breakthrough on Climate Compensation and 7 Other Takeaways

But success was marred by the failure to find agreement on phasing down all fossil fuels or otherwise build on emissions-cutting commitments made at last year’s UN summit in Glasgow. “Many parties — too many parties — are not ready to make more progress today in the fight against the climate crisis,” Timmermans said after reaching the COP27 agreement. The final deal “is not enough of a step forward for people and the planet.”

It’s a damning indictment of the UN process from a consummate insider, and it comes against the brutal backdrop of increasingly extreme weather such as the monsoon flooding in Pakistan over this summer that left at least 1,700 dead and some $30 billion in damage. Pakistan, for its part, celebrated the breakthrough on loss and damage.

After more than two weeks of climate haggling involving nearly 200 nations, all of which had to agree on the final text, COP27 has revealed a marked shift in power within the diplomatic process that produced the 2015 Paris Agreement. Bold new agreements to curtail emissions are now harder, in large part because of the energy crisis that prompted a worldwide scramble for new natural gas supplies. At this moment, cooperation meant to tackle inequities between developed and developing nations is more doable.

The final COP27 document without crucial progress on emissions came about, in part, from a concerted effort by petrostates such as Saudi Arabia and Russia to fend off more carbon-cutting ambition and pledges that would undermine the oil and gas production that fuels their economies. Oil-producing nations were empowered by a hands-off Egyptian presidency that failed to launch early negotiations, foster trust among countries or even circulate draft proposals in time that could form the basis for consensus.

It didn’t start out that way. Delegates and observers were jubilant on Nov. 6 after a swift earlier agreement to launch the first-ever formal debate over the issue of loss and damage — COP-speak for how to help developing countries getting battered by intense storms, searing heat waves and other climate-exacerbated weather disasters. The nations most vulnerable to rising temperatures created little of the planet-warming pollution that has intensified these extreme impacts. Yet the moral case for compensation from rich nations hadn’t even appeared on a COP agenda until now.

There was major work to do to advance the issue at COP27. The top US climate envoy, John Kerry, had insisted before the summit that there was no way countries could agree to establish a new funding facility by the end of the conference. The largest negotiation bloc of vulnerable nations, known as the G77+China, demanded nothing less. At the same time, rich countries wanted to push developing nations harder on pursuing economic growth with green energy and stepping up decarbonization efforts to limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

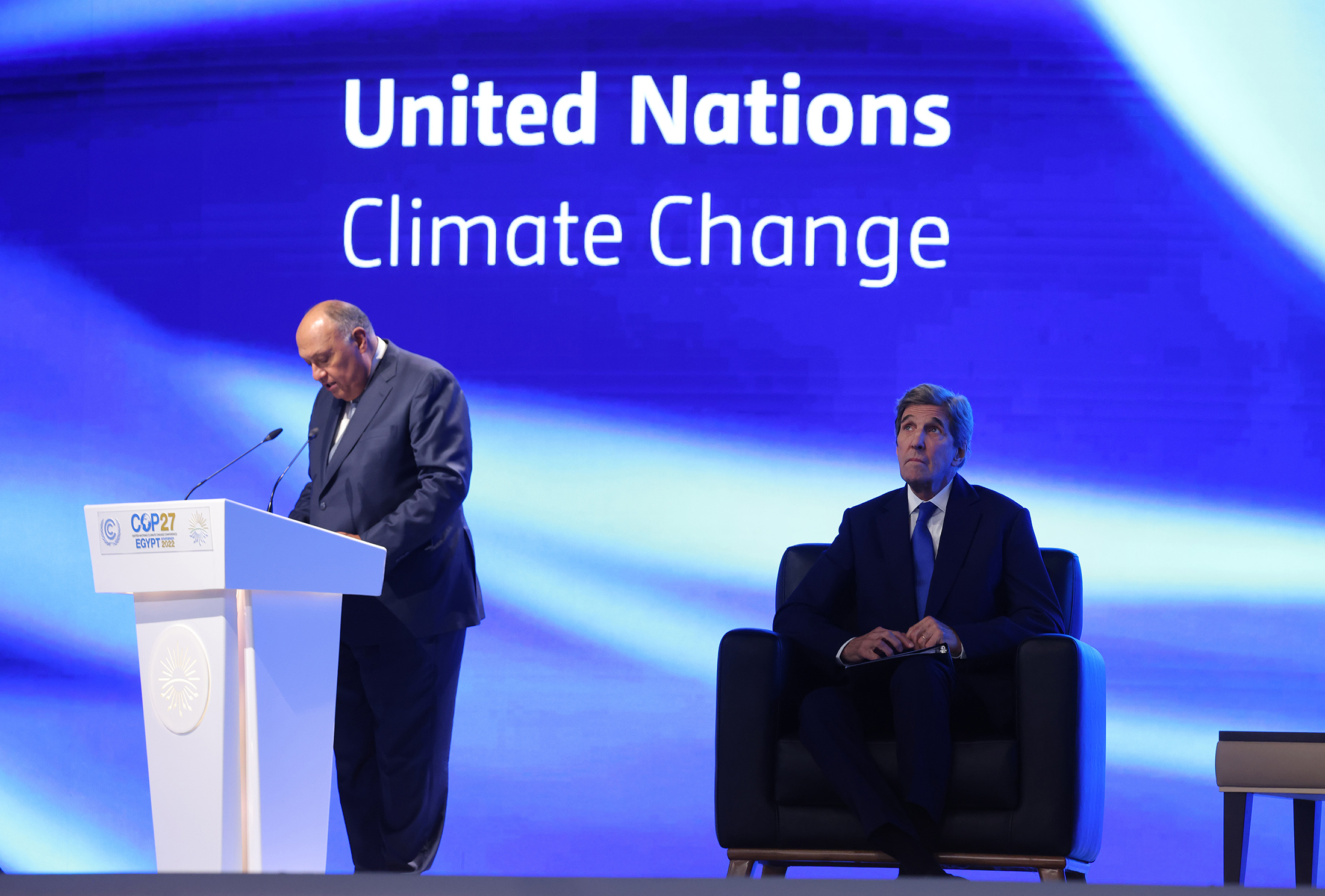

This tension made for halting negotiations at the conference center in a Red Sea resort town, where thousands of participants and observers found long lines for food and empty water dispensers. A sense of frustration built among delegates as the days passed under sweltering sun. By the middle of the second week, there was no hint of breakthroughs on any of the major issues. Even debates over smaller, less controversial topics — such as rules governing carbon markets — remained unresolved. The Egyptian official serving as president of COP27, Sameh Shoukry, had to keep a host of topics under negotiation during the conference’s final days.

As the second week wore on, a stalemate emerged between developing and developed countries over the new fund for loss and damage. Concessions by the EU and other rich nations that might be compelled to pay into the fund did little to resolve the impasse. As that fight ground on, there was building momentum around India’s call for countries to pledge to phase down all fossil fuels — not just unabated coal, as they had promised a year earlier in Glasgow.

Shoukry warned delegates that “time is not on our side,” with just days remaining in the talks. “There is still a lot of work ahead of us if we are to achieve meaningful and tangible outcomes of which we can be proud.”

Behind the scenes, according to delegates and observers, the Egyptian COP27 presidency was displaying little urgency. Normally in the late stages ministers would be digging into proposed language for a final political decision, or “cover text,” that’s issued at the end of the summit. These broad consensus statements form the basis for global climate action by laying out temperature goals, carbon-cutting pledges and finance plans. But the Egyptian officials running COP27 weren’t initially planning for ambitious cover text at the end, and so they hadn’t drafted boilerplate language ahead of time.

By the evening of Wednesday, Nov. 16 — after 10 days of talks, and just 48 hours before the conference’s official close — nothing formal had been circulated. Shoukry had been notably absent from the process, both publicly in press briefings and behind closed doors in meetings with delegations. This presented a marked contrast to the hands-on style of his predecessor in the COP presidency, Alok Sharma of the UK, who took an active approach to COP26 talks in Glasgow last year.

On Thursday morning, delegates woke to a sprawling, 20-page document that presented an assortment of options for final language. It was full of redundancies and conflicting passages. Egyptian Ambassador Wael Aboulmagd later explained that it had been whittled down from more than 50 pages of competing proposals, after omitting ideas the presidency deemed too controversial.

Among the casualties: any possible pledge to phase down oil and gas as well as coal — a blow to India, the EU and scores of other countries now supporting the effort. The text also left only placeholders for a future compromise on loss and damage, rather than the concrete offer sought by the G77 bloc of developing countries. Developed nations felt blindsided by proposed language that would compel them to dramatically decarbonize and “attain net-negative carbon emissions by 2030,” a feat that would strain both political and technological wherewithal.

“If all of you were to be young people like me, wouldn’t you have already agreed to do what is needed to save our planet?”

Sharma, Timmermans and Steven Guilbeault, Canada’s climate minister, spent parts of Thursday pleading with Shoukry in private to ensure the final COP27 outcome would build on the Glasgow declaration, rather than backslide from it. When delegation leaders gathered later that day to assess progress, it was clear little had changed. Timmermans sought to break the logjam by offering a two-part deal: The conference would agree to establish a new loss-and-damage response fund, with details worked out over the next year, and in return countries would vow to peak global emissions by 2025 and phase down all fossil fuels.

That EU proposal was largely passed over by the Egyptian presidency, which on Friday morning released a draft decision text that once again left out any kind of promise to phase down fossil fuels as well as a commitment to peak emissions by 2025. There was little visible progress toward a potential loss-and-damage fund, which developing nations called an unforgivable omission.

“Anything other than the establishment of a loss-and-damage fund at COP27 climate talks is untenable,” warned Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s climate minister, speaking on behalf of the G77 bloc.

Tensions had emerged over a push by many developed nations, including Germany and other EU members, to ensure a broad donor base for any new fund for loss and damage. While the onus should be on historically high greenhouse gas emitters, they felt rapidly developing nations behind enormous emissions — namely, China — should also contribute. “We need a financing system that includes the biggest emitters, said Annalena Baerbock, Germany’s foreign minister.

As conference staff started pulling down flags, unwiring displays and dismantling pavilions, 10-year-old Nakeeyat Dramani of Ghana beseeched delegates. “Please, do not renege on your responsibility,” she implored them inside a packed meeting on Friday. “If all of you were to be young people like me, wouldn’t you have already agreed to do what is needed to save our planet?”

But the odds of success appeared to be diminishing. Ministers from island nations were already starting to fly home late Friday — which had been the official end date for the conference — as they were unable to bear the expense of rebooking travel or staying for an extended time. A delegation from Botswana, among others, started scrambling to book new arrangements as negotiations headed into overtime. Talks were also complicated by John Kerry’s Covid diagnosis on Friday, which forced the seasoned diplomat — known for leveraging handshake diplomacy and personal relationships to forge compromise — into quarantine.

Shortly after midnight Saturday, some delegates were summoned by the Egyptian presidency for a closed-door look at portions of a new drafted text focused on loss and damage and efforts to boost climate mitigation. Country officials were permitted 20 minutes to analyze the unpublished material in a closed room and barred from removing the documents. One official called it highly unusual.

For the EU, the draft decisions were riddled with holes. On loss and damage, the text said that the funds could apply to all developing countries rather than just the most vulnerable. The Europeans found the mitigation language even worse — weaker than Glasgow, according to some — because it explicitly ruled out new climate targets or goals. Timmermans had conditioned a new loss-and-damage fund on stronger emissions cuts. He hadn't gotten it.

Still, the EU gambit had helped shift the debate over loss and damage, successfully boosting pressure on the US to yield on the issue while helping prompt oil-rich Canada to back down from a fight against a fossil-fuel phaseout. The key breakthrough on loss and damage came after texts published early Saturday afternoon. To break the deadlock, the EU took the unusual step of convening the “Friends of the Presidency,” a select group of countries and negotiating blocs. The EU, US, the G77 and the Alliance of Small Island States assembled with the Egyptians for the talks.

The G77, which includes many island states threatened by rising seas, had shown a remarkable solidarity in their quest for a loss-and-damage fund that would apply to all developing countries. But in the overtime meeting, the EU pressed the island states: Are you really happy not to be prioritized for funding? Representatives from the Maldives took a 30-minute timeout, came back into the room and broke with the G77, according to a person familiar with the matter.

As a result, the final version of loss-and-damage text targeted funding to “developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.” The proposal leaves the door open for contributions from developing-but-high-emitting nations, such as China. And, in a win for the US, the language makes clear the new fund isn’t meant to duplicate existing efforts, with details developed over the next year. The goal is to operationalize the new funding arrangements at next year’s UN climate summit in Dubai.

“Just changing a few paragraphs, we actually got something which respects both sides,” said Espen Barth Eide, Norway’s climate minister.

Despite the breakthrough on loss and damage, clashes over mitigation intensified at this point. As planes droned overhead, delegates were locked in an intense fight over even maintaining the emissions-cutting ambition adopted at COP26. Officials from Saudi Arabia had pushed for a one-year mitigation work program, an effort that aims to close the gap between 1.5C and the current trajectory headed almost one degree higher. The US, EU and other countries wanted the program to run through 2030.

Ministers from New Zealand, Norway and Canada complained that the latest text was a step backward. “There can't be any backsliding,” Canada's Guilbeault told reporters. “We cannot leave Sharm El-Sheikh by having abandoned the possibility of keeping 1.5 Celsius alive, and right now we are very concerned that is what is being proposed.”

Failure on the mitigation package threatened to tank the deal on loss and damage. New Zealand climate change minister James Shaw said at this point things were “tantalizingly close” and he felt “it would be an incredible shame for it to fall over right now.” Delegates privately worried that if they didn’t strike now, future political shifts in the US and other countries would make a new fund impossible.

But Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia and other oil-producing countries were digging in against expanded language on fossil fuels, according to people familiar with the matter. During a two-and-a-half hour meeting of the heads of delegations late Saturday, US negotiator Trigg Talley announced the country was ready to go even further and support a pledge to “phase out” unabated oil, gas and coal. This took the US a step further than language to merely “phase down” fossil fuels.

But it wouldn’t matter. Delegates from oil-rich nations insisted that the energy proposals were unbalanced and unacceptable. Language to phase down oil and gas was a red line they would not cross. When final text was released — after ministers had already filed in to a final meeting around 4 a.m. Sunday — there was no phase-down pledge and new language had been added to further protect petroleum interests. Countries would now be agreeing to an urgent need for rapid emissions reductions, including through an increase in “low-emission” energy, a term Norway’s Eide bemoaned and that was left undefined. It could be read as supporting more natural gas.

Shoukry was intent on quickly pushing through the loss-and-damage compromise. Minutes after convening the session just before dawn Sunday — with some staff still sleeping in rolling office chairs in the back — he brought up the text and asked for its adoption. With a gavel bang just a few moments later, it was done. Nearly 200 nations had just agreed to create a loss-and-damage fund for vulnerable countries bearing the brunt of climate change.

The countries that wanted to see stronger climate ambition were still weighing their options, including possibly intervening to demand the insertion of pledges on emissions peaking by 2025 and phasing down fossil fuels. After successfully appealing for a half-hour break to review the newly released text, delegates from the so-called High Ambition Coalition, including Norway, Canada and the UK, huddled to strategize. Sharma spoke with US officials Talley and Sue Biniaz.

For a moment it looked like developed nations would press the issue on the floor, sparking a fight that would reveal deep divisions over the pace of the world’s pivot from fossil fuels. But Shoukry restarted the meeting and began calling up portions of the final documents, one after another, swiftly asking if there was any objection and then gaveling down in assent before any placards were raised. Timmermans sat stony faced, his eyes locked on Shoukry. Moments after applause marked the adoption of the main cover text — dubbed the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan — delegates from the US fled out the back.

Norway’s Eide quickly followed. The mitigation work program could have been worse, he told reporters, and at least the ambition “does not scale down from Glasgow.” But his glum face betrayed his disappointment.

Inside, some ministers were still seething. The final calculus, for many, was whether to demand last-minute changes and risk a floor fight that could cause the entire deal to collapse, taking the progress on loss and damage with it. But the disgruntled nations weren’t united on their demands, and negotiators were exhausted after a sleepless final night. Shoukry had run out the clock.

“We are all tired — except, of course, for you, Mr. President,” Timmermans said in an address a few moments later, an apparent thinly veiled reference to Shoukry’s hands-off leadership. “We are faced with a moral dilemma because this deal is not enough on mitigation” but the alternative would be to “walk away and thereby kill a fund that vulnerable countries have fought so hard for for decades.”

Sharma fumed that there were fights at every step. “Those of us who came to Egypt to keep 1.5 degrees alive and respect what every single one of us agreed to in Glasgow had to fight relentlessly to hold the line,” he said. That target “remains on life support.”

Tuvalu’s foreign affairs minister, Simon Kofe, summed up the mix of success and failure that characterized the end of the summit in Egypt. Loss and damage counted as a tremendous gain: “It has been a long time coming — three long decades — and we have finally delivered climate justice,” Kofe said. However, he added, “we haven’t achieved an equal success” on emissions and that “has made Sharm El-Sheikh, regrettably, a missed opportunity for a truly successful COP.”

--With assistance from , and .

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.