Australia’s Soil Carbon Pioneer Sees an Offset Fortune in Dirt

(Bloomberg) -- There are billions of dollars to be made from capturing emissions in Australia’s dirt, according to the only developer to have been awarded national offset credits for using the land management technology.

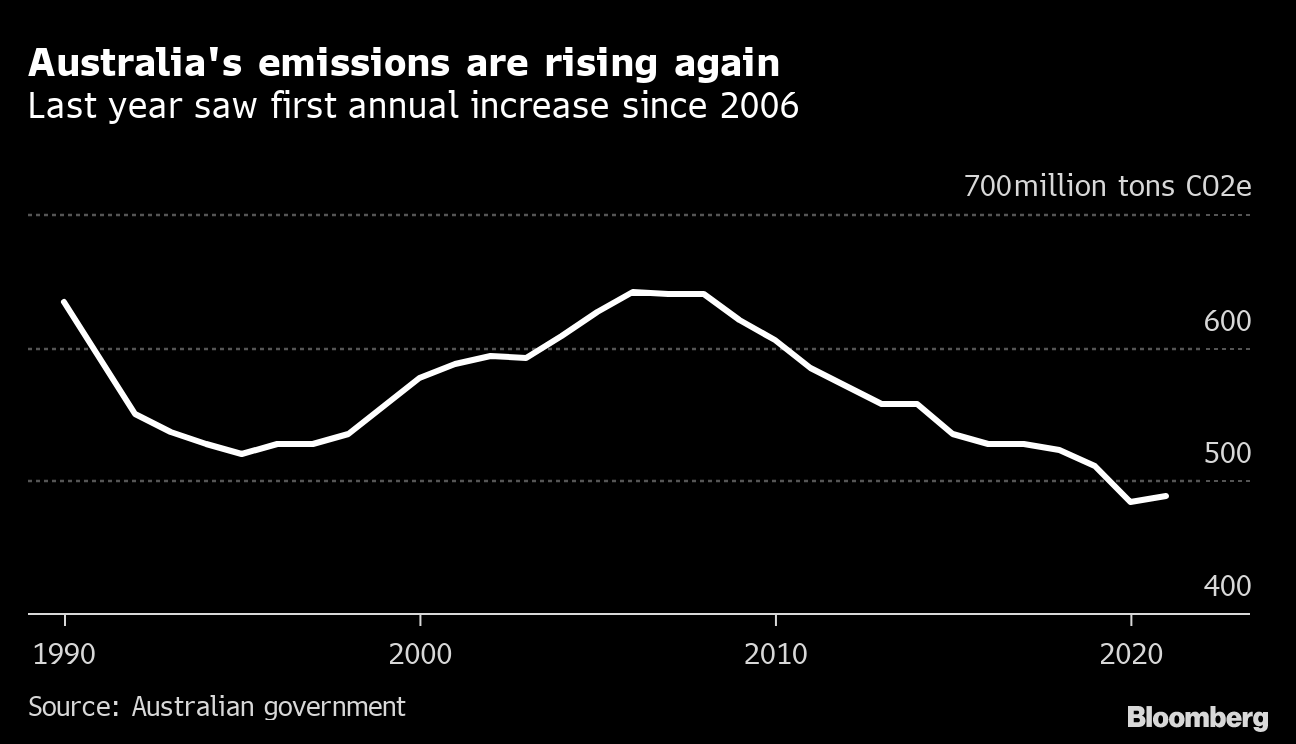

AgriProve is seeking to install carbon farming projects across an area almost the size of Cuba and sees potential to store more than 25 million tons of the nation’s emissions in 2030, equivalent to 5% of last year’s total. That would generate income of A$750 million ($517 million) a year at current prices for the Australian Carbon Credit Units the projects would receive.

The developer expects to generate ACCUs this year for eight different sites across the country, after in 2019 becoming the first and only recipient to date of the credits for so-called soil carbon sequestration, Managing Director Matthew Warnken said in an interview.

Techniques to store emissions in the soil are relatively simple — ranging from seeding pastures to changing stocking rates and grazing patterns — but the time and cost of proving that greenhouse gases are actually being captured has been a huge barrier to its development.

“We’re talking about hundreds of millions of tons of abatement that can come from soil with no downside,” Warnken said. “We’re particularly bullish about the soils because it’s not taking land out of production, so we don’t have that land trade-off use you might have with a forest — you can plant the trees, get the carbon — but then you can’t use the land for anything else.”

Read more: Tougher Climate Action Seen Boosting Australia Carbon Credits

In order to reach its more ambitious targets, AgriProve will have to convince investors increasingly concerned about the credibility of carbon credit systems and projects to bet on expensive technology. The high costs and long waiting times have been a barrier to many landholders, with AgriProve receiving the only credits to date among the roughly 350 projects registered with the nation’s Clean Energy Regulator.

Warnken compared the high costs involved in testing soils for carbon to the early days of solar, once a prohibitively expensive technology that’s now become one of the cheapest sources of power. He estimated that carbon farming is about 20 years behind solar in terms of its cost curve and ramp up in use across the nation.

“Soil carbon can directly sequestrate and remove carbon in the atmosphere, while having a positive impact on the local farming community,” said Bae Ho-hyun, a sustainable investments manager at Seoul-based Platform Partners Asset Management. “There's a high possibility that these projects will generate high-quality carbon credits and if that's case, it's likely to stoke market demand, leading to higher premiums.”

Read more: Wall Street’s Favorite Climate Solution Is Mired in Disagreements

Still, there are questions about soil carbon sequestration’s viability amid an increasingly volatile climate, which scientists say can actually impact the level of abatement. Soil loses carbon during periods of drought, while increased chances of bushfires during dry periods pose an added threat to trees and vegetation that have stored tons of carbon.

“If there's no measured increase in soil carbon, there's no carbon credit creation,” Warnken said about the possibility that using the methods could fail to actually remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. “We have that as a part of our risk. How we mitigate that risk is building a bigger portfolio.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.